Ryan Conger thought his athletics career was over.

Rounding third base in a baseball game in 2017, the LeTourneau University sophomore hit an uneven spot in the field. He heard a pop in his knee and knew right away it was his ACL. He was gutted.

“I was like, man, if I don’t have baseball, I really don’t know what I’m going to do,” he said. “I make good grades, but it was only because I wanted to play baseball.”

Ryan Conger competes in the 2021 NBA 2K league playoffs four years after an ACL tear ended his college baseball career. Conger said he planned to use his winnings to help his father open a food truck.

Jim Cowsert, 2021 NBAE | Getty Images

Sidelined with what can be a career-ending injury, Conger channeled his competitive energy into a video game called NBA 2K. The native of Palmer, south of Dallas, worked his way up the basketball game’s rankings, playing against others from around the world, and was drafted in 2018 by a professional competitive gaming affiliate of the Dallas Mavericks NBA team.

In September, Conger and his team won their second straight championship on a virtual basketball court, marking Conger as one of the best NBA 2K players in the world and earning him a cut of a half-million-dollar prize. His competitive career wasn’t over; it just looks a whole lot different now.

Conger and his teammates occupy one of the many big and bright stages of competitive video gaming—known as esports—and their work and winnings are made possible by the booming new industry that attracts 26.6 million monthly viewers who watch gamers compete in a vast array of virtual venues. Beyond sports games, the online universe extends to strategy and battle arena games and even traditional board games, like chess.

Esports brought in more than $1 billion in revenue for the first time in 2021 and has given rise to a whole host of career paths for professionals in marketing, information technology, game design, broadcasting and many other fields—in addition to the game-playing pros on arena stages and online. Now educators at schools are preparing students to take advantage.

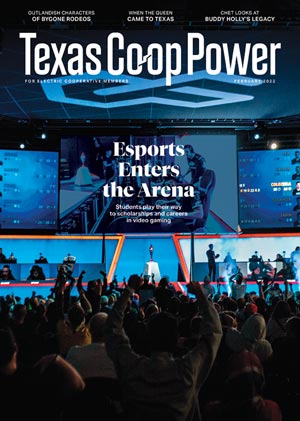

The Mavs Gaming Hub in Dallas, site of last year’s NBA 2K playoffs.

Jim Cowsert, 2021 NBAE | Getty Images

“Esports is not the five professionals sitting on the stage,” said Matt Tarpley, a member of the Texas Scholastic Esports Federation board. “There’s 10 times more people behind the scenes doing all sorts of other work.”

In 2018, Tarpley approached the principal at the high school in Merkel, west of Abilene, where he worked in IT. He pitched a gaming team that would be managed by an esports-centered marketing class.

“I said, ‘Man, I don’t necessarily understand this, but I do understand that our kids are going to be into it, so let’s try it,” Principal James Stevens said. Tarpley taught the class and coached the team, and more than two-thirds of the school’s students expressed interest in the class.

“We used to get in trouble for playing video games, but now it’s really cool because we see that video games help us develop our problem-solving skills, our critical-thinking skills,” said Jansen Wilhite, who took over for Tarpley in 2021. “These are all great skills to have for when we enter the job force.”

Wilhite grew up with video games, playing Donkey Kong as a child and World of Warcraft with her husband as an adult. Her degree is in microbiology, but she teaches physics and now Merkel’s gaming course, where her students learn all about the types of video games, how they’re developed and how to foster positive gameplay environments.

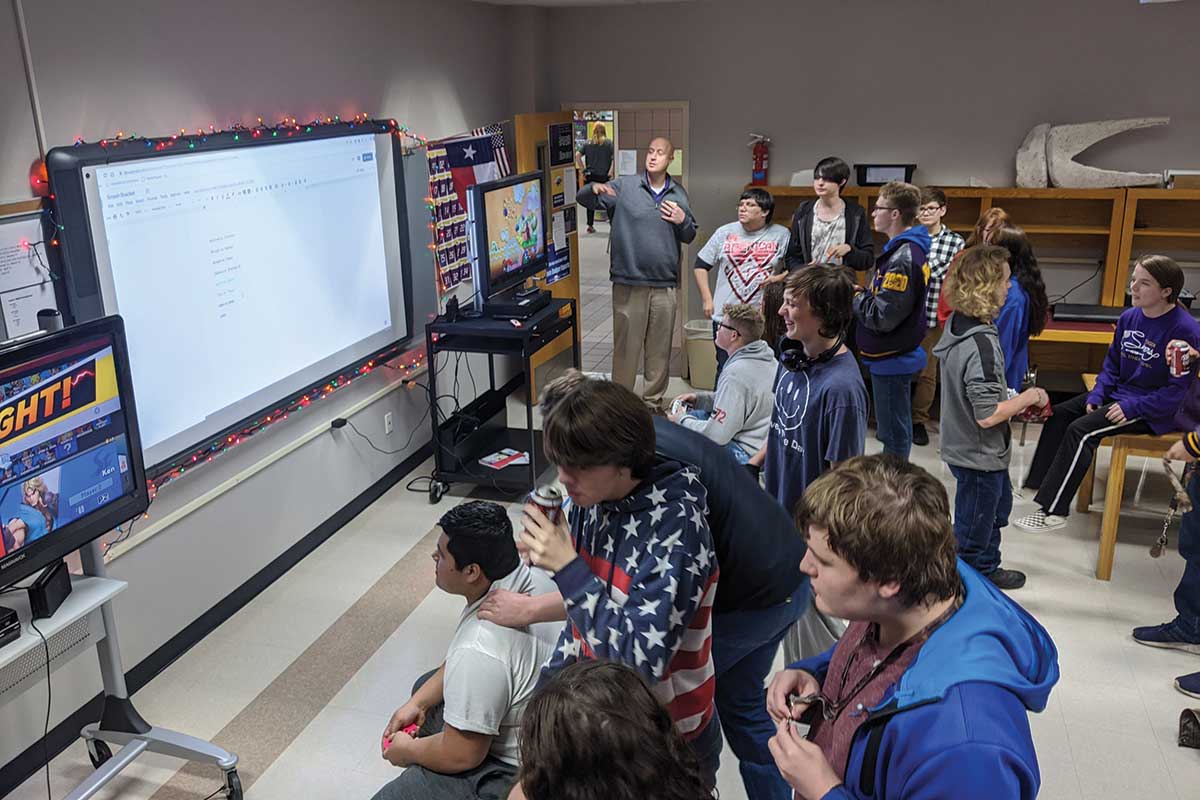

The Merkel High School esports marketing class hosts a tournament.

Courtesy Matt Tarpley

“I never anticipated a career in video games, but here we are,” Wilhite said. “It’s really cool for me to get to use both halves of myself at work.”

Wilhite also runs Merkel’s after-school esports team, which competes in online chess and other video games against teams across Texas. Like the team at Sabine High School, in Upshur Rural Electric Cooperative’s territory in Northeast Texas, where technology director Randy Cox was surprised by the buy-in he received from the superintendent.

Mean Green Dominates

Watch the University of North Texas take down Louisiana State University in a national playoff game.

“When you tell someone you want to start a program where we do competitive video games, I expected to get a little bit of a laugh, but he was very supportive,” Cox said. “It’s one more thing that students can get involved in with our school.”

Merkel, Sabine and more than 400 other high schools across Texas now field esports teams, and even some middle schools are beginning to form clubs—part of a pipeline forming to feed some 250 colleges across the country that offer nearly $15 million in scholarships to esports competitors and to feed the array of fields that support all of it.

Eldarnurkovic | Stock.adobe.com

Dallas public schools boast 60 esports clubs, but rural districts like Merkel and Sabine are making sure their students don’t get left behind. They’re working cooperatively to learn what’s working and what isn’t, how to get buy-in from administrators, where to get resources for computers and equipment, and how to form leagues while the University Interscholastic League ponders official esports inclusion. Not every school has gamers on staff, fast internet or money for high-powered computers.

“Our rural schools in our area have always said, ‘Hey, we understand that we can’t do this by ourselves, but if we come together, we can get things done,” said Shawn Schlueter, a technology consultant who works with educators in 13 counties. “We’re starting to see that where administrators and even interested teachers are calling us and saying, ‘You know, I see that [esports] could be valuable. How do I get going with it?’ ”

Texas Wesleyan University students compete.

Courtesy Texas Wesleyan University

That value extends beyond the classroom. Esports can have profound benefits for students who aren’t interested in traditional sports, extending to them the positive effects of team building, communication and community support that have long been available to athletes.

“I always say that esports programs are primed for the kids who slip through the cracks of schools,” Schlueter said. “Even in a rural school where everybody has to do something, there are groups of kids that do nothing, and this helps engage those kids.”

Principal Stevens has seen it firsthand at Merkel.

“It’s attracted a lot of the kids who showed up at 8 and left at 4,” he said. “I’ve seen better participation, better grades, better attendance out of all those students, and it gave them something to be proud of involved with the school.”

Some of those students followed Tarpley to McMurry University in Abilene, where he now coaches the esports program.

“They’re on track to get a degree all because of esports,” Stevens said.

In Texas, dozens of smaller and lower-profile colleges like McMurry are cashing in by enticing competitors with scholarship money. The University of North Texas and the University of Texas at Dallas field some of the most competitive esports programs in the nation, part of a burgeoning esports hotbed in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, where the $10 million Esports Stadium Arlington—the largest such venue in North America—has space for 2,500 spectators.

University of North Texas students celebrate at a national tournament.

Courtesy Psyonix llc

But there are opportunities everywhere for esports professionals like Kyle Murto. He was preparing for a college soccer career when a string of injuries put him in the hospital, where he cracked open his laptop and climbed the ranks. Pro teams didn’t come calling, but Blinn College did. Now Murto helps coach the Brenham-based school’s esports team, which competes against Division I giants—and wins.

“Smaller schools don’t have that name recognition, so we have to go out and make a name for ourselves before the universities really get into the game,” Murto said.

At McMurry, Tarpley is focused on education and personal growth, not wins and losses. He holds workshops for content creation, personal branding and livestreaming and finds graphic design, statistics, broadcasting and other work for students to master.

“Everybody wants to be in this space,” he said. “It’s going to be everywhere eventually. It’s just a matter of time.”

Tarpley’s team meets regularly with a mental health coach—esports’ version of an athletic trainer—and he strives to make sure women are included in an activity that’s been dominated by men. He’s not forming the next Ryan Conger but the next Jansen Wilhite—multiskilled gamers and leaders who can cultivate programs like Merkel’s.

“I had several local schools call me, several local principals that know me. They’re like, ‘Hey, we hear y’all are doing esports. Can you tell me about it?’ ” Stevens said.

“Of course, my first thing is, to be really successful you have to have a Matt Tarpley.”