As dusk falls on a warm summer evening, I’ve joined J. David Bamberger and a few close friends at a table about 50 yards from a gaping hole on a hillside at his ranch near Johnson City.

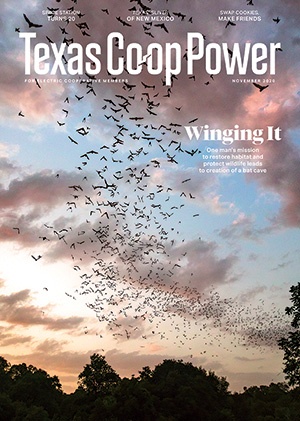

As we nibble chips and salsa, a single bat emerges from the opening. In a flash a hawk swoops down, snatching the fluttering scout in midflight. A few minutes later, with sunlight quickly fading, a few more bats appear. Soon a narrow stream of flapping shapes forms, like a horizonal plume of campfire smoke.

Bamberger, a former door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman who co-founded the Church’s Chicken chain, used his fortune to buy this once-overgrazed property in 1969, paying just $124 an acre. He named it Selah, Bamberger Ranch Preserve and began nurturing it, removing nonnative species and planting indigenous grasses. The dry, eroded Central Texas landscape sputtered back to life. Today the 5,500-acre oasis features flowing creeks, fields of waving grass and towering trees and serves as a laboratory for land conservation.

It’s also got a bat cave, or “chiroptorium,” as Bamberger, 92 and still hiking or exploring his property nearly every day, calls it. (The word hasn’t made it into dictionaries, but it’s a standard at Selah, which itself is a biblical word whose definition is debated but to Bamberger means “to stop, pause, look around and reflect.”)

While volunteering as a trustee with Bat Conservation International’s Bracken Cave in the 1990s, Bamberger met BCI founder and bat expert Merlin Tuttle, who taught him the environmental benefits the furry, sometimes pecan-sized mammals provide. Bats gobble up tons of insects across the country each night, Bamberger learned, saving farmers more than $3.7 billion a year in crop damage and pesticide use. Bamberger, a member of Pedernales Electric Cooperative, got the wild idea to lure a bat population to his own ranch by building a bat cave. Constructing a bat habitat, he figured, meshed with his mission to restore rangeland and protect wildlife.

Bamberger overlooks a pond from one of his favorite spots on the preserve.

Eric W. Pohl

“People laughed at the idea,” Bamberger tells me. We met and became friends more than a decade ago, when I first wrote about his work. “When people laugh at you, sometimes you back away,” he says. “Most successful people continue on.”

After consulting with bat experts, architect Jim Smith designed a 30-by-100-foot, three-domed habitat with a special observation room where scientists and visitors could watch the bats through a plate glass window. They picked an easily accessible spot near water with a clear flight path. Then they went to work building the structure of concrete and gunite, backfilled it with dirt and covered it with native vegetation.

Newspaper reporters flocked to the ranch in 1998 to report the story. Now all he needed was a resident population.

Bamberger hauled in a load of bat guano to make the cave more appealing, but the bats turned up their noses. He brought in a small occupied bat box to lure a population, but the bats didn’t stick around. Still, Bamberger persisted.

“If it doesn’t work, it’ll hold a hell of a lot of wine,” he rationalized.

J. David Bamberger shows an indigenous grass that thrives at the preserve.

Eric W. Pohl

Every once in a while, a few bats would show up. “I’d be about to rapture,” Bamberger says. But the stream of bats he dreamed about didn’t move in until four years later, after biologists realized that the few bats that discovered the cave were smashing into the observation window. After they boarded up the window, the bats moved in.

“Unbelievable,” Bamberger says, telling the story of driving up to the site and discovering the new residents. “Tears are running down my face. I can’t believe what I’m seeing. The bats are pouring out.”

He felt vindicated, especially since the San Antonio Express-News was printing a story that very week, dubbing the cave “Bamberger’s Folly” and noting that he’d spent more to build a house for bats than most people spend building a home for their family.

When he phoned biologist Tom Kunz, though, the bat expert warned that the emergence was likely a fluke and that a migrating group had probably just stopped over temporarily.

But the bats came back. And since they arrived in big numbers in 2002, they have never left. Today the ranch is home to year-round populations of Mexican free-tailed bats and cave myotis, another type of bat. Thermal imaging scans show that as many as 400,000 individuals pack shoulder to shoulder along the chiroptorium walls during the summer and fly out nightly to forage for insects. In the winter the population dwindles to 3,000–15,000.

Bamberger walks with author Pam LeBlanc.

Eric W. Pohl

“Our bats are very strange,” says Jared Holmes, staff biologist at Selah, equating the population to the bat version of a wild college fraternity house. While a large maternal population inhabits the space during summer months, it changes when temperatures drop. “We don’t know if the winter colony is just a bunch of lazy males [from northern populations] that don’t want to fly all the way south or something else,” Holmes says.

The maternal population generally shows up in April or May and remains until the heat eases in September or October. Bamberger built the chiroptorium to hold a million individuals, but biologists today believe the cave’s current population represents full capacity. “If you go in there, it’s wall-to-wall bats, and as [evolutionary biologist] Gary McCracken put it, they are a possum’s crawl off the floor,” Holmes says.

Bamberger likes to say you could run around naked all day and never get bitten by a mosquito at his ranch. And while that’s not quite true, the bats do keep down the insect population at Selah.

“It’s David’s bat cave of dreams,” Holmes says. “We’re lucky David tried it.”

Sunset at the preserve.

Eric W. Pohl

But testing also has shown the cave carries a high load of the fungus that causes white nose syndrome, the disease that has killed millions of bats across the country, mostly in the Northeast. When conditions are right, the fungus blooms, creating an itchy, white, mushroomlike growth on the bats’ faces that wakes them from hibernation. That’s less of a problem in warmer places like Central Texas, where they can still find water and insects year-round, but devastating in colder climates. So far the Selah bats have not shown signs of the disease, but as a precaution, Holmes hopes to pressure-wash the chiroptorium this winter, at night while the population is out foraging.

“If we lose bats, we lose ecosystem services—all that free pest control and food for other animals,” Holmes says. “Bats are in trouble, and we have a very unique opportunity to study how these man-made bat caves can function with fungus and virus and how we can disinfect their habitats. It’s an opportunity to see how we can help bats, and it’s great to have a proven design that we may be able to scale down for smaller colonies.”

Besides, bats don’t deserve their negative reputation, Holmes and Bamberger say. The mammals have long been maligned, equated with evil in old films and described as blood-sucking vermin.

“But everything in the natural world, even things we despise, plays a role in the conservation of planet Earth,” Bamberger says. “From the very beginning of my time here, I knew I wanted to make the ranch something special with Mother Nature. I realized the potential of bats—they would be another thing I could brag about, teach from and demonstrate.

“This is small potatoes, but I think my small potatoes are terribly important.”

Pam LeBlanc is an Austin-based journalist specializing in outdoor adventure and environmental issues. She’s had several close encounters with bats. While crawling through a remote cave last year, one flew up her pants leg. (She didn’t get rabies.) Her first book, My Stories, All True: J. David Bamberger on Life as an Entrepreneur and Conservationist, came out in September.