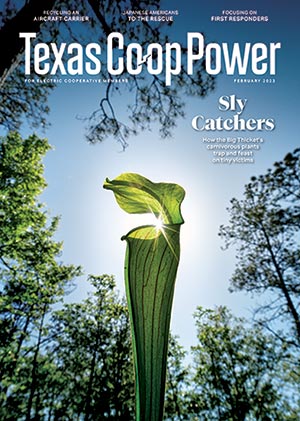

Hundreds of slender, funnel-shaped plants line a boardwalk at Big Thicket National Preserve, where I’m trailing biologist Andrew Bennett on a warm April morning.

They look hungry.

The lime green, red-veined throats of the foot-tall plants gape, like baby birds awaiting a worm delivery from a parent. But these unusual plants have other plans for dinner: unsuspecting insects.

Four of the five types of carnivorous plants that grow in North America—the pitcher plants we’re now admiring, along with sundews, bladderworts and butterworts—are found here and elsewhere in East Texas. (Venus’ flytraps, whose eating parts resemble a hinged lima bean with teeth, don’t grow in Texas; they’re endemic to the Carolinas.)

I’m on a quest to find all four Texas natives, and Bennett, acting chief of resource management at Big Thicket, has offered his help.

We’re off to a good start. We have no trouble finding these trumpet-shaped pitcher plants, which grow by the thousands along the mile-long, aptly named Pitcher Plant Trail in the Turkey Creek Unit of the 113,000-acre preserve.

Carnivorous plants, Bennett says, thrive in soils that are low in nutrients. They’re not endangered, but they do require a very specific habitat, and these East Texas bogs provide it.

First, pitcher plants need wetlands. The groundwater in this part of the preserve is close to the surface, so the ground tends to stay wet. They also need periodic fire, to create a more open understory and to recycle nutrients into the soil. Rangers at the Big Thicket use prescribed burns to do that. And finally, they need insects, which provide nutrients in soils without much nitrogen. The Big Thicket has no shortage of those.

Pitcher plants grow by the thousands in Big Thicket National Preserve in East Texas.

Dave Shafer

The entrance to the preserve’s Pitcher Plant Trail is outside the town of Warren.

Dave Shafer

Tiny, colorful sundews use enzymes to absorb insects that get trapped in their glistening hairs.

Dave Shafer

For some people, carnivorous plants call to mind the off-Broadway show Little Shop of Horrors, based on a 1960 film about a ravenous bit of vegetation. Audrey Jr., as it was called in the original film (it was remade in the 1980s), was a cross between a Venus’ flytrap and a butterwort, and it needed human blood—not just a few insects—to survive.

Unlike Audrey Jr., pitcher plants don’t feed on humans. They don’t use quick movements to hunt their food, either. And they’re a lot smaller than the theatrical version of the plant.

Insects are attracted to pitcher plants because of their color, nectar and scent. When a bug lands on the waxy lip of the plant’s funnel, it slides down into the tube, where downward-pointing hairs keep it from climbing out and escaping. Eventually, it winds up in a tiny pool of fluid at the bottom of the funnel. Enzymes in that fluid slowly eat away at the wasps, ants and other foraging insects that land there, and the plant absorbs nutrients from the “bug soup.” Cut one open and you might find several disintegrating insects stacked up inside it.

During our walk, the sun lights up the pitcher plants like rows of bright green candles. Bennett and I admire them for a while, strolling up and down the boardwalk. Then he leans over, pointing out something low to the ground. I follow his finger and see it: a small, roundish plant hugging the ground. It’s made up of small arms, each one tipped with a fingernail-sized fleshy paddle flocked in glistening red hairs. Those hairs secrete a sticky substance—and beware any insect that sets foot in it. The sundew, like the pitcher plant, uses enzymes to slowly absorb any prey that gets caught.

The best time to see both plants is late April and May.

“It seems like people always expect them to be a lot bigger, especially sundews, or to trap more actively, like Venus’ flytraps do,” Bennett says. “These are more passive. They wait for bugs to fall in or get stuck.”

Still, they’re charismatic plants, and this concentration of them is among the largest in the U.S.

“I don’t know of a bigger stand in Texas,” Bennett says.

Biologist Andrew Bennett scoops bladderwort from a swamp.

Dave Shafer

Delicate strands of bladderwort.

Dave Shafer

With pitcher plants and sundews checked off our list, Bennett and I head back to our trucks to continue our hunt. It’s a 20-minute drive to our next stop down a quiet, narrow road inside the preserve, where we pull off and squirt a little bug spray on our ankles to fend off the mosquitoes before striking out into the forest.

The going is slow. There’s no trail to follow here, so we slog our way through thick underbrush and around tall trees. Everything looks the same to me, and it’s hard to maintain a straight line, so Bennett consults his GPS. He knows the exact coordinates of where we’ll find the bladderwort.

At one point a flash of movement catches my eye, and I spring back just in time to avoid a copperhead, a venomous pit viper with beautiful gray and rust-colored markings.

The snake blends into the ground cover so well that it disappears from sight a moment later.

Soon we reach a swamp the size of a baseball diamond. The ground squishes underfoot at its edges, and the place smells organic and earthy. Emerald-colored moss covers logs like velvet, and tannins have turned the shallow water the color of tea. A barred owl hoots in the distance. The whole place feels primordial. I wouldn’t be surprised to see a dinosaur emerge from the gloom.

The elusive butterwort escaped the author’s eye, but our photographer spotted one.

Dave Shafer

A shaft or two of light filters through the leaves into the bog in front of us, where tupelo trees stand knee-deep in the water. Bennett, who is wearing boots, sloshes in. A moment later, he’s found what he’s looking for.

Bladderwort, which looks like delicate strands of dill fringed with clusters of pinhead-sized balls, floats on the surface of the brown water. Those tiny balls are the plant’s namesake bladders, and they not only keep the plant afloat; they trap the tiny aquatic bugs that it needs to survive.

And unlike the pitcher plants, which passively trap their food, the bladderwort moves using a reflexive process called thigmotropism. As insects are lured into openings on the tiny bladders, they close, trapping the prey inside.

That leaves just one plant on my checklist: The wily and elusive butterwort.

This time, we’re out of luck. We can’t find any of the plants, with their taco-shaped leaves dotted with droplets of sticky ooze. Bugs looking for water get stuck in the butterwort’s secretions, triggering enzymes that break down their soft body parts.

That’s OK. Now I have another reason to return to East Texas: to continue my search for these unusual little plants.

I glance at the vegetation around me. Until now, I’ve thought of all these flowers, bushes, trees and vines as a sort of soft green wallpaper to the outdoors. Now, the carnivorous ways of some of these plants have given me a new jolt of respect.