The man whose name is on Brenham’s famed Simon Theatre never saw it completed, but the renovated theater still reflects his vision a century later.

The historic venue on Main Street in Brenham, midway between Austin and Houston, turns 100 this year. It’s thriving today because of a multimillion-dollar restoration that saved it from the brink of crumbling, and its story tells the story of Brenham, a town that has found a way to mine its past to preserve its future.

In the 1920s, the theater, originally with more than 700 seats and a balcony and separate entry for Black theatergoers, emerged from the imagination of James H. Simon, son of a Polish immigrant, who grew up in Brenham in the entertainment industry and died three months before the first performers took the stage.

Simon was a boy when his family moved to Brenham, arriving with some of the first Jewish settlers in the region and staying because that’s where the railroad ended, according to Sharon Brass, a local researcher who created the A Century of Simon exhibit, on display at the historic theater earlier this year.

The Simon Theatre in downtown Brenham.

Natalie Lacy Lange | Courtesy the Barnhill Center at Historic Simon Theatre

The Simon family arrived in the mid-1860s, and James’ father, Alex Simon, opened a mercantile store. He eventually bought the Grand Opera House in town and turned it into a family-friendly venue for musical performances, receptions, recitals, political meetings and vaudeville, which was quickly becoming the most popular form of entertainment at the time.

As the terminus of the Washington County Rail Road, constructed in 1860, the county seat’s population doubled every decade until 1900—and with it grew Brenham’s reputation as an entertainment hub, along with the opera house.

When Alex Simon died in 1906, his sons took over. They opened the stage for an even wider variety of local performers, including Black singers from the nearby Brenham Normal and Industrial College, a postsecondary school for African Americans, according to Tina Henderson, who grew up in Brenham. She’s president of the Texas Ten Historical Explorers, a research organization focused on the freedmen’s communities around Washington County.

James H. Simon sold the opera house in 1918 and started making plans to build his own theater. He teamed up with Houston architect Alfred C. Finn to make plans for a majestic performance space with an upstairs section for Black theatergoers so they could watch the shows too.

The theater’s stage and auditorium during its extensive reconstruction.

Kevin Boggus | Courtesy City of Brenham

“They built the theater with [integration] in mind,” Henderson says. Although Simon didn’t live to see the completion of his theater, he was ahead of his time in terms of wanting to make art available to more people, Henderson says.

“Segregation was very harsh, but there were some people who understood it was unkind,” she says. “They had to abide by the laws, but I think they were trying to accommodate and do what they could” to make the performances accessible to all.

Variety acts had been around for a long time, but it wasn’t until the late 1800s that “vaudeville,” a word borrowed from French, became a household term to describe a kind of show performed by artists, comedians, magicians—anyone who had something amazing, interesting or entertaining to show off.

At the height of vaudeville, as many as 50,000 performers traveled in troupes to perform in thousands of American cities, including Brenham. This lasted from the end of the Civil War into the 1930s, when in-person variety shows gave way to those broadcast on radios and, later, television.

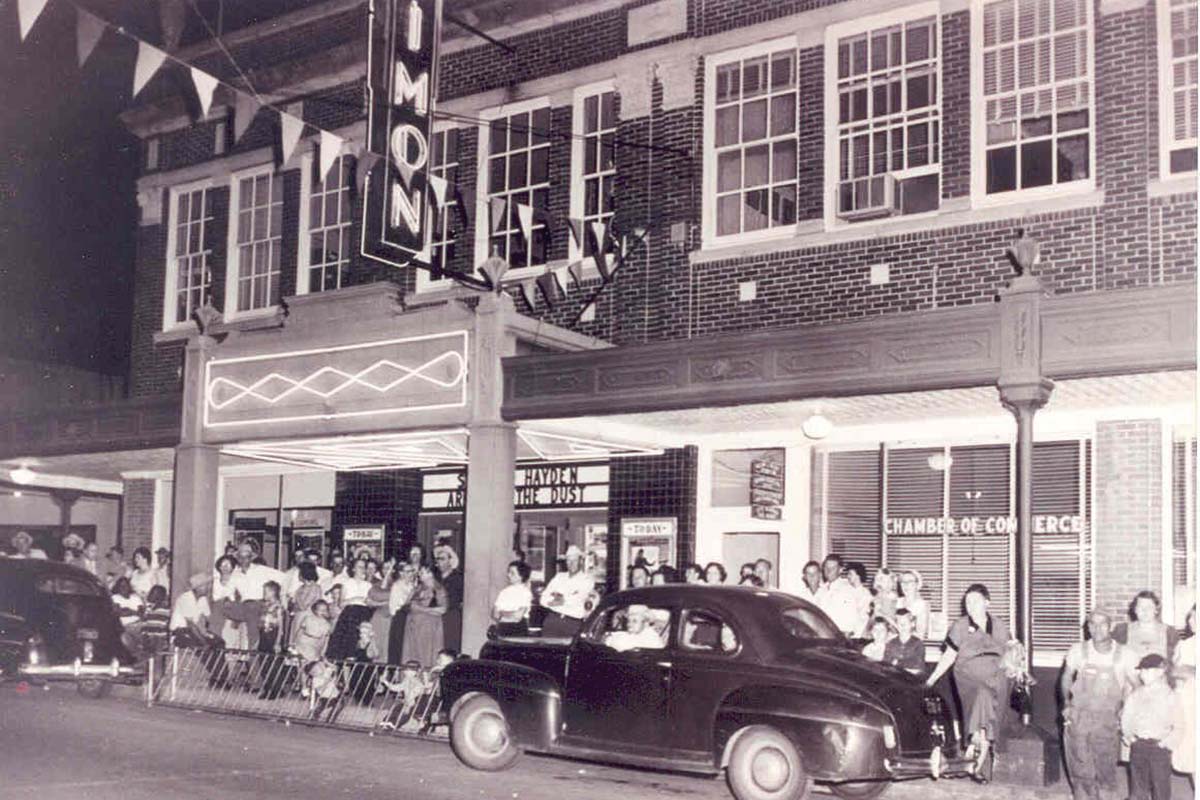

The 1954 Western film Arrow in the Dust drew a crowd to the Simon.

Courtesy The Barnhill Center at historic Simon Theatre

The earliest vaudeville shows took place in saloons and beer halls, but their popularity soared, thanks in part to the growing popularity of circuses during this time. Venues like the Grand Opera House in Brenham opened in places served by the railroad to make it easy for the performers to get there and for visitors to come to the shows, according to Brass.

Many of the vaudeville performers who came through Brenham would have been well-known to people who lived there, thanks to telegraphs and the newspapers that came in on the railroads daily from the East Coast.

Vaudeville shows were on the decline in the 1920s due to the rising popularity of silent films, but they were a crucial part of the early days of the Simon Theatre because the shows brought in big names, like Adelaide Prince, who was born in London but grew up near Brenham.

After Simon’s death in 1925, the theater was sold to the Stuckert family, who ran it for almost 50 years before selling it. The venue continued to host movies and events into the 1980s, when competition from drive-in theaters, shopping malls and home video ultimately caused the theater to shutter. After a showing of Night of the Living Dead on October 31, 1985, the theater went dark.

Jennifer H. Eckermann, former tourism and marketing director for the city, is a Brenham native who remembers when all those historic buildings were an afterthought.

“The Simon wasn’t in great shape,” she recalls. “There was a lot of talk about it being demolished to build a parking lot. For so many downtowns, that was the answer.”

In 1999, after a career at Blue Bell Creameries, Eckermann started working with the nonprofit Main Street Brenham. By that time, the Simon Theatre had become a Chinese restaurant and then sat vacant, waiting for demolition or the kind of restoration that takes a miracle to pull off.

She joined a handful of people who had a vision for what the brick building could be. Thanks to that community spirit that led James H. Simon to build the theater so many years ago, local boosters raised more than $1 million for the restoration project. The Simon Theatre reopened in 2004 with 321 seats.

The Malpass Brothers brought their traditional country and bluegrass music to the Simon in September 2024.

Natalie Lacy Lange | Courtesy The Barnhill Center at historic Simon Theatre

The group eventually raised another $1 million to renovate the ballroom and retail space that was part of the original design. The facility now operates as the Barnhill Center at Historic Simon Theatre, with shows throughout the year from performers such as Grammy Award-winners Ricky Skaggs and Marty Stuart to tribute bands celebrating the Carpenters, the Eagles and the Andrews Sisters.

Eckermann says the project sparked a downtown revival that continues to this day and that the success story of the renovation reflects changing attitudes toward preservation.

“People are always coming and going,” she says. “You might own this building now, but one day, you won’t.” The current keepers of the keys—and the stories—are trying to tell new stories while also keeping the old ones alive.

The Simon Theatre could last another century, but Eckermann says that depends on always finding new ways to bring in people. They’ve had success in recent years with themed movie nights and school performances.

“You have to be thinking about the next generation and what would be appealing about this theater to them,” she says. “What can it continue to offer to the community?”

For its 100th year, the Simon Theatre team kicked off the celebration with performances that included juggling, dancing and comedy. “It was fun to have something for everybody,” Eckermann says. “It’s still vaudeville.”