Editor’s note: An article on growing olive trees in Texas, published in the March 2002 edition of Texas Co-op Power, produced a flurry of calls from people who were interested in getting into the olive-oil business. Here, we return to the Texas fields to see how the Texas olive oil pioneers are faring.

——————–

A giant, boxy, blue beast on wheels lumbers through Southwest Texas farmland, belching smoke and harvesting row after row of silvery-leafed trees laden with marble-sized fruit, some the color of a cactus pad and others a fine merlot. The much-anticipated fall harvest for the Winter Garden region’s newest—and one of the world’s oldest—crops has finally arrived at the Texas Olive Ranch near Carrizo Springs.

At the edge of the orchard inside the cavernous frantoia, or olive press house, on Jim Henry’s 67-acre ranch, a new mechanized press is doing its job under the supervision of California olive experts. Thousands of the Texas-grown olives flow along a conveyor belt, where they are washed and woody debris is extracted, before yielding a stream of amber-green oil to be stored in 48-gallon drums. The press processes an amazing 3,000 pounds of olives an hour.

After the harvest, Henry reflected on the yield of almost 100 tons.

“We accomplished a great deal,” he says. “It’s finally materialized where there really is something to this. We have to look at the big picture that there is now an olive industry, and it works. The hope is that people can make a living doing this.”

It certainly appears that they are. With a yield of 50 gallons per ton of olives, and the precious oil selling for $12 to $25 per 12.5-ounce bottle, the Texas Olive Ranch partners already have recouped a big chunk of their $1 million investment in the first year of commercial production. (There is less expensive extra virgin olive oil in grocery stores, but Texas olive oil is still rare and pulls a hefty price. It could be argued that Texans—think wine industry—are buying the olive oil because they’re proud of Texas’ agricultural products.)

As the farm’s 40,000 trees of mostly Spanish stock acquired from California mature—it takes about four years on average for them to do so—the company’s future olive production and profits should increase exponentially.

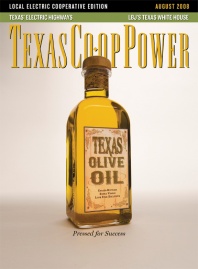

Henry, a Dallas businessman, numbers among a handful of entrepreneurs who are “betting the farm” that the nascent olive oil industry in Texas will be the state’s next wine industry, which is now more than a quarter of a century old. After more than 10 years of fits and starts, unbridled optimism and dashed hopes, a new breed of 21st century “wildcatters,” from Dimmit County in southern Texas to Hays County in Central Texas, struck pay dirt last year with a bumper crop of olives. The first 100 percent estate-bottled Texas olive oil has finally hit the market.

Henry helped found the Texas Olive Oil Council in the 1990s and has been fine-tuning olive tree cultivation in the Lone Star State for more than a decade. With Americans’ love affair with all things olive, the stakes for the state’s dogged olive growers are huge.

Henry and his partners believe the successful 2007 harvest will translate into a burgeoning crop of olive growers, especially in South and Southwest Texas, where winters are typically mild and not as likely to produce extreme temperature fluctuations—perhaps the biggest threat to younger trees that make up the bulk of the state’s olive orchards. Established olive trees, by contrast, are hardy and can tolerate dry conditions and grow in marginal soil.

Harvesting methods are important, too, when it comes to gathering olive crops. Unlike the Texas Olive Ranch, most Texas olive operations depend on family, friends and workers to pick the fruit by hand. It’s a much more tedious process, but one that produces less bruised fruit and damage to the trees than farm machinery.

Soaps and Scents

Saundra Winokur, who operates an organic olive orchard south of San Antonio within earshot of Interstate 37, imported an ancient stone-wheel press from Egypt to do her limited pressing. Because the oil is processed outdoors, it can’t be sold for human consumption, but she reports that the “taste was fabulous.”

Instead of marketing the oil from her crop, Winokur pickles most of her olives and uses olive-tree leaves to produce an extensive line of handcrafted, all-natural skin-care products; she also offers chocolate truffles infused with olive oil and unusual soaps made with olive oil, olive leaves, lavender, flowers and grains. Look for Sandy Oaks products at Shades of Green and the Guenther House in San Antonio.

Winokur returned from extensive travels abroad with the idea of planting her own olive trees to complement her family’s ranching tradition. Today, she runs cattle on 218 acres and oversees a 40-acre orchard planted with 10,000 olive trees bearing names such as arbosana, frantoio, pendolino and mission. The latter is the only variety developed in America, and the root stock was brought up from Mexico by Franciscan friars more than 400 years ago.

“We’re still in the experimental stages,” Winokur said. “I figured the trees that would grow in North Africa or Spain would do best in Texas, and that has pretty well proved true.”

Sandy Oaks boasts 22 varieties of Spanish, Greek, Italian and Tunisian olive trees that line fences, decorate the ranch’s handsome grounds and undulate in a sea of shimmering silver toward the orchard’s distant tree line.

Faring best in Sandy Oaks’ 2007 harvest were the cold-tolerant Spanish arbequina and Italian pendolino, as well as manzanilla and the hardy Texas mission variety. But Winokur has high hopes for two young Tunisian varieties and koroneiki trees that originated on the Isle of Crete. The Texas rancher was so buoyed by last year’s harvest that she has purchased her own olive press for this year’s crop.

Like Henry’s Texas Olive Ranch, Sandy Oaks is experiencing a growing demand from customers who want to grow their own trees. Winokur sells trees wholesale to places like the Natural Gardener in Austin, Rainbow Garden in San Antonio and online via the Olive Barn website. Her trees cost from $10 to $95 and are sold in 4-inch to 15-gallon containers. Texas Olive Ranch Foreman Tony Correa propagates and sells several varieties of olive trees—arbequina, kor-oneiki and arbosana—in 1-gallon pots that sell from $6 to $12.50.

Most Texas-grown olive trees put on clusters of white blossoms in April and set fruit during the warmer summer months. Most varieties are ready to harvest in August or September.

As for Winokur’s products, all items are available in the Sandy Oaks Olive Orchard store, a Tuscan-style rock building with a tin roof. Winokur does offer Sandy Oaks’ own blend of imported extra virgin arbequina and arbosana olive oils from California that are ideal for bread dunking or cooking. Visitors may schedule a tour of the orchard and the ranch’s picturesque facilities, where horses pace a corral and a handful of cats skulk about. Cooking classes have been added to the ranch lineup, and dinner under the stars is on Sandy Oaks’ menu for this summer.

Bella Vista Meets Success

Jack Dougherty, who founded Bella Vista Ranch near Wimberley in the mid-1990s, finally experienced an excellent harvest last year after a decade of trying. Nonetheless, he sounds a note of caution amid the general optimism.

The straight-talking entrepreneur views raising olive trees in Texas as anything but a get-rich-quick scheme. He says Texas growers need to approach the olive industry as a business and exercise patience in seeing it mature. Dougherty believes it may take a little longer to understand the dynamics of what it takes to grow olive trees successfully in Texas.

“Everybody in Texas thinks he can go out and plant olive trees and make a million dollars,” says the former Silicon Valley computer executive who witnessed the rise of California’s olive industry in the 1970s and ’80s. “I don’t think we’ll really know for 20 years if Texas has a viable industry.”

Dougherty, who in 2001 completed the first commercial pressing of a Texas-California olive oil blend, notes that olive trees are an alternate-bearing crop, meaning they typically produce well every other year. Therefore, olive production this fall may not reach last year’s bumper-crop level.

Dougherty and other Texas growers extol the olive’s myriad health benefits and uses. Olive oil tastes good, feels good on the skin and contains healthy omega-6 oil. In addition, an enzyme (olecanthal) in extra virgin oil is an anti-inflammatory thought to play a role in preventing heart disease and cancer.

“People in the United States don’t look at olive oil as a food product that’s like a butter substitute as they do in other parts of the world,” Dougherty says. “That’s the true opportunity we have in Texas—to create an olive oil that serves as a main dietary intake.”

Rob McCorkle is a Kerrville-based writer and media relations specialist with the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department.