Anyone driving by one evening last August probably thought we were nuts. Seated in plastic lawn chairs, binoculars at eye level, my husband and I both had our heads craned upward at a huge live oak in our front yard.

A few weeks before, a pair of golden-fronted woodpeckers had drilled a hole high in a thick branch. Now we knew why. A little head kept popping out of the cavity, eager to devour whatever the exhausted parents brought to eat.

Throughout summer, James and I enjoyed other mini-dramas in our yard: Three black-bellied whistling ducks roosted in the same oak. Amid a thicket of lantana, a yellow garden spider caught grasshoppers on her large orb web. Black-chinned hummingbirds battled over sugar-water feeders. Delicate queen butterflies swarmed a thick patch of mistflowers. On a nearby butterfly weed, tiny queen caterpillars chomped through green leaves, quickly growing chubby and long.

The more we planted, the more fun we had watching nature respond. So we added more natives, including Texas betony, rock rose and several varieties of salvia. We bought more birdbaths and hung more hummingbird feeders. For toads, we set out shallow water bowls and halves of a broken pot for shelter.

Our efforts to create a wildlife habitat earned our yard certification as a Texas Wildscape through the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. The program encourages landowners to create pockets of habitat for the benefit of birds, small mammals, reptiles and butterflies. (Habitats must comply with local and county ordinances.) Since 1994, Texas Wildscapes has certified approximately 3,500 residential yards, school grounds and corporate parks across the state.

To qualify, a landscape must be planted with at least 50 percent native vegetation, provide year-round food and water for wildlife, and offer shelter, such as rock piles, nest boxes and toad houses. (Bonus: Native plants generally require less care and water.)

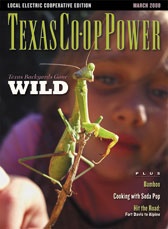

The program targets two major objectives: offset habitat loss due to increasing urban sprawl and encourage Texans—especially children—to get outside and interact with nature.

“Three years ago, I had a butterfly on my finger, and a girl in junior high was scared to touch it!” recalled Mark Klym, Texas Wildscapes coordinator. “A reaction like that means we’ve got to get our young people more involved with nature.”

Northside Elementary

As a prime example, Klym points to Northside Elementary School in Angleton, where students, staff and parents tend a half-acre Texas Wildscape. The fenced area features separate ponds for koi (non-native) and turtles plus herb, vegetable and butterfly gardens. Bird and hummingbird feeders as well as a purple martin house attract scores of birds. At one pond, youngsters love visiting Rosie, an American red-bellied turtle (also a non-native) who “rules the roost.”

“Some of our students don’t have a backyard of their own, so our habitat is very exciting to them,” said instructor Pam Williams. “Teachers utilize the habitat tremendously in their science curriculums and as rewards for students who make high grades and have perfect attendance.”

Benches and picnic tables provide places to sit and watch whatever happens to be unfolding that day in the habitat: Tadpoles wiggling in the pond, dragonflies sunning on rocks, plump tomatoes reddening by the dozens.

“We’re within the monarch coastal flyway,” Williams added. “The kids have held butterflies still wet from their chrysalises and watched as they flew away. Our students are well versed in all aspects of nature, thanks to our wildscape.”

Star of Texas B&B

Near Brownwood, Debbie and Don Morelock tend a certified garden around their home and complex of guest cottages, called Star of Texas Bed and Breakfast. Wildflowers, bird feeders, birdbaths, a small pond and a variety of native plants—such as Texas sage, salvias and American beautyberry—create a lush habitat that’s frequented by birds, butterflies and other critters.

The couple especially enjoys watching a pair of eastern screech owls that raise their young each year in a constructed nest box hung on a dead tree. “They’re such cute creatures,” Debbie said. “They’ve brought me the most joy.”

In the future, the Morelocks hope to entice an endangered species to their garden. “Horned lizards have been seen on a nearby ranch,” she said. “On our property, we have several beds of red ants, which they eat.”

El Pasoans John & Kathy Kiseda

In El Paso, Kathy and John Kiseda last year glimpsed a greater earless lizard and red-spotted toad in their yard, a certified Texas Wildscape. A number of other birds and animals have visited, too. Hermit thrushes dined on turk’s cap and yaupon holly. Gambel’s quail fed on and roosted in junipers. Fresh scat marked recent stopovers by gray foxes.

“A giant hesperaloe sent out its first-ever flower stalk this past year,” John said. “It attracted verdins and various hummers, who vied for the copious nectar from its waxy flowers.” Within their yard, the couple has identified 120-plus species of birds, 11 mammal species, 10 herptile species and 30 species of butterflies and moths.

“We love our wildscape because we think it’s the right thing to do, and we also use it as a learning tool for visitors,” said John, an animal curator at the El Paso Zoo. “Our yard is often a part of local garden tours.”

Bentsen Palm Development

Lori Rhodes emphasizes education, too. She and her husband, Mike, own one of the state’s largest certified habitats: a 2,000-acre master-planned community under way in the Rio Grande Valley town of Mission. The entire Bentsen Palm Development, which will include single-family residences, a gated adult community and RV park, embraces the Texas Wildscape program.

“Our roadways, parks, common areas, entrances and community centers are all certified,” Lori said. “We’re teaching the concept of Texas Wildscapes to homeowners and how to plant natives. One way is through our 35-acre Texas Wildscape Demonstra-tion Site, which flourishes with more than 10,000 plants and trees that feed and protect wildlife. We follow a natural organic program and have an abundance of wildlife, especially butterflies.”

In some of the development’s parks, the Rhodes purposely left dirt piles and other “wild” areas where youngsters can dig around, explore and create their own adventures. “We believe that in order for people to want to protect our environment and be a part of the solution, not the problem, they need opportunities as children to experience nature,” Lori explained.

Kids at Heart

Like children, James and I love finding weird bugs, strange egg cases and critters of all kinds, including toads and an occasional rat snake (they’re harmless). We admire the snakes from a respectable distance and relocate the toads to a tangle of vines, shrubs and dead limbs that’s overtaken a small backyard corner.

“There’s someone in the sanctuary!” I exclaim whenever I spy a toad languishing in one of the shallow water bowls we put there. Then we both dash out to see.

Yes, the neighbors probably think we’re both nuts, but we sure have fun in our wildscape!

——————–

Sheryl Smith-Rodgers is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power. She’s written about everything from Greater Tuna to the Caverns of Sonora for us.