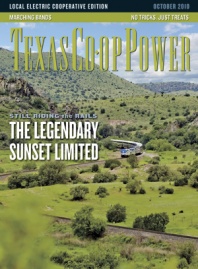

The train’s eight, double-decked passenger cars shimmer silver like a mirage in the afternoon sun just north of Big Bend National Park. In Alpine, I learn that this train, the Sunset Limited, runs from New Orleans to Los Angeles three times a week, westbound and eastbound. Primed by reading mystery and spy novels set on the Orient Express and Trans-Siberian Railway, I decide the 18-hour journey from Houston to El Paso is tailor-made to fulfill a fantasy: I can finally experience a comfortable, overnight trip on a legendary train, even if it means flying from Harlingen, where I live, to Houston to catch it.

Early one winter evening, my husband, Guy, and I enter Houston’s Amtrak station on a dead-end downtown street. The fabulous night skyline of the metropolis twinkles overhead. Inside the station, displays of vintage railroad brochures rekindle excitement for rail’s golden age of streamlined locomotives.

When the Sunset Limited arrives in Houston, sleeping car attendant Oscar Jimenez, a fit 39-year-old wearing a red Amtrak tie, welcomes us aboard. While he transforms our lower-level roomette with two wide seats into upper and lower berths, we head to the observation car, walking through the 90-foot-long, double-decker passenger and dining cars on the upper level. The Sunset Limited, which has been in operation more than 100 years, pulls out of Houston promptly at 9:50 p.m. Our elevated perch lets us spy into backyards as the train slowly picks up speed, its whistle warning cars at crossings. Once the city lights disappear, only our reflections remain visible in the tall windows.

A suitcase absolutely cannot fit in a cozy, 7-by-3 1/2-foot roomette. I change in the dressing room next to the sleeping car’s compact bathrooms and luggage storage bin.

With our roomette’s curtains and glass door pulled shut, we settle down. Three carpeted steps lead up to my bunk with its own reading light and mesh gear bag. Guy reminds me to secure the webbing from my bunk to the ceiling so I won’t slide out as the train rolls west. The muffled, rhythmic clack-clack of the train accented by an occasional distant train whistle lull us to sleep. Around 3 a.m., I wake to see silhouettes of passengers boarding in San Antonio. This is one of the Limited’s seven stops on its 900-mile trek through Texas, says Jimenez, who has 21 rooms under his care for the entire 1,995-mile trip to Los Angeles.

By 7:30 a.m., I’m watching Southwest Texas go past from the lower bunk. The gray morning offers glimpses of dry washes and barbed-wire fences strung on weathered posts. Guy reports he’s slept like the proverbial baby rocking in a cradle.

The train is carrying a full load of 243 passengers on this rainy day. Sleeping car accommodations include meals, so we seat ourselves in the white tablecloth dining car for mushroom omelets and thick French toast. Our breakfast companion Russ Optiz, traveling from Houston to Arizona, explains, “I hate flying, and it’s too far to drive. You get to see the sights this way. Plus, I like standing up, being able to walk around, and then go lie down for a nap.”

The Sunset Limited’s melting pot and social center is the observation car, where passengers in sleepers and coach seats mingle. Window-facing seats occupy two-thirds of the car. Tables where people snack, play cards and visit fill the rest.

On Tuesdays, National Park Service guides interpret the views for passengers from Del Rio west to Sanderson. Education Specialist Lisa Evans and two volunteers from the Amistad National Recreation Area board the train to present their award-winning Trails & Rails program. They point out the Rio Grande, which we won’t glimpse again until El Paso, 436 miles and eight hours away. Amistad Dam comes into view and then we see solitary homes, each with its own aging windmill. Volunteer Fern Herrington draws our attention to dark-green creosote bushes spaced out like a checkerboard. The plants are so efficient at sucking up water that even their own seeds can’t sprout near them.

Mixing natural, cultural and railroad history of Southwest Texas, the guides chat with the passengers. The 1872 completion of this southern transcontinental railroad route spelled the end of wagon trains, we learn. Herrington, a retired teacher, passes around laminated photographs of plants, snakes, birds and pictographs found in this arid land. For a moment, we are suspended on the Pecos River bridge 265 feet above the water. Then, paralleling the track, we see old Highway 90, abandoned 40 years ago and being erased by drifts of sand and tough spiky grass.

“Unless you point things out, people don’t think there is anything to see,” Herrington explains. “I’ve been told we make it interesting and bring what they’re seeing to life.”

Jim Miculka, meanwhile, the national coordinator for the National Parks Service’s Trails & Rails partnership with Amtrak, tells me he is testing a podcast guide developed for 101 points of interest along the full Sunset Limited route. Miculka, who is based at Texas A&M University, says the podcast—the first of its kind—is celebrating Trails & Rails’ 10th anniversary this year.

Miculka points out that train crews have their own jargon. For example, when engineers and conductors reach their 12-hour work limit and must be rotated out, no matter where the train is, railroaders say, “the crew died.” He tells me of a passenger who, finding the train stopped in the middle of nowhere in the middle of the night, asked the sleeping car attendant what was going on. He was told, “The crew died.” The rumors were flying around the dining car the next morning.

Guides and crew get off at the Sanderson whistle-stop where winter clouds are dropping lower on the mesas. I spot corrals made of railroad ties and a curious sign: “Deer Shop.” As the train passes through Marathon, the fabled adobe-brick Gage Hotel and the funky Marathon Motel, a revived motor court with compact cabins and its own windmill, pop into view. So does snow, now dusting the ground and drifting onto yuccas and lechuguillas.

In the dining car, over Angus burgers and salads accented by apples, nuts and crumbled cheese, our lunch companions confess their addiction to the no-hassle, no-hustle mode of train travel. “I don’t bother putting on my regular makeup,” a well-groomed woman admits.

When the train stops in Alpine, I’m disappointed only because there’s not enough time to grab a beer from The Holland Hotel’s microbrewery, across the tracks (the brewery is now closed, but the historic hotel is well worth an overnight stay). One heedless passenger, I hear, wanders off and is left behind.

Although the train is traveling at 79 mph, the observation car is quiet, half-filled with people reading. In the coach cars, some passengers are tucked under quilts in roomy seats that resemble recliners with plug-ins for DVD and game players.

Time feels suspended as the snow piles up deeper outside. Tumbleweeds frame cattle-loading pens. Clouds cluster like sagging white socks near mountain bases. A train trip gives you a chance to enjoy the journey itself, Guy and I agree, sightseeing from the privacy of our roomette. Trains bring a different perspective to what you see besides being more relaxing, more fun, than a car or plane ride.

“What train travel takes is time,” observes Jimenez, the sleeping car attendant, as he makes up berths with tightly tucked sheets.

At 4:40 p.m. our time runs out, and we stand in front of El Paso’s majestic, 105-year-old Union Depot Passenger Station. We promise to find the time to travel by rail again, soon, as the train’s silver cars glide west into the sunset without us.

——————–

Eileen Mattei is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.