Aaron and Lindsey Hockenberry didn’t know.

Their families, who drove to the hospital in Victoria from Houston, Katy and Shreveport, Louisiana, for Lindsey’s cesarean section, didn’t know.

Their doctor didn’t know.

“Everybody was there expecting to bring home a baby and get to hold her,” Lindsey said.

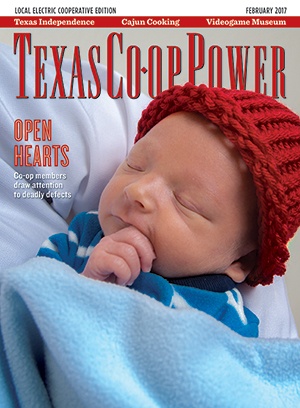

Instead, baby Londyn came out blue. She wasn’t crying and was barely breathing. Within six hours, she was on a helicopter bound for Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi. The next day, the full-term newborn underwent open-heart surgery.

Aaron broke down. The Iraq War veteran met his wife with tears when she had recovered enough from her own surgery to make the trip to Driscoll with her sister.

“At that point, we had been married for two years and together for a year before that,” Lindsey said. “I had never seen him cry like that, and that’s probably what scared me more.”

No one knew until that day that Londyn had a rare heart defect that would require her to be hospitalized four times over the next eight months. Heart defects affect tens of thousands of babies born in the U.S. every year, but Londyn’s was more serious than most.

“A lot of parents don’t know that their babies have this, and they’re just blindsided,” Lindsey said. “They think they have a healthy baby, and all the sudden they don’t have a healthy baby.”

One Southwest Texas woman is doing all she can to bring attention to the issue.

“I Think We Can Do This”

Nancy Johnson has a command center of sorts spreading out across her Sonora family room. Towers of clear plastic totes brimming with skeins of red yarn, prayers printed on rolled paper and bound with bows, and countless tiny, red, auburn and red-and-white knit hats have taken over one wall, nearly burying an antique stove. Against another wall sits her desk, where an iPad and a cellphone connect her to a network of knitters, each denoted by a tiny red heart emoji next to their name in her phone address book. There are stacks of letters, neatly pressed and bound, newspaper clippings and thank-you cards ready for stamps.

Johnson knits red hats, and she leads an army of hatmakers from across Texas’ Co-op Country that is raising awareness of congenital heart defects.

It all started in 2015 when Johnson first contributed to the Little Hats, Big Hearts project. Started in Chicago, the American Heart Association initiative outfits babies born in February—American Heart Month—with colorful, keepsake headwear, along with a card that explains the seriousness of the problem, and asks parents to post a photo of their hat-clad newborn on social media using the hashtag #littlehatsbighearts to raise awareness.

Congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect and affect nearly 1 percent of births in the U.S. annually. At 40,000 a year, their prevalence is increasing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Not long after Johnson mailed off her three contributions to the project, she needed a stent for a heart problem of her own. She discussed the project with her cardiologist, Dr. Michael Blanc, at San Angelo Community Medical Center, and inspiration struck.

“I asked him, ‘What do you think about doing something like this for the state of Texas?’ ” Johnson said. “He said, ‘I think we can do this.’ ”

So Johnson, 76, a member of Southwest Texas Electric Cooperative, with the help of husband Jerry, a former 43-year board member of the co-op, got to work, buying yarn, asking friends to join in, and spreading the word. They named their group “Knitting Hats for Little Hearts,” and they were the first of their kind in Texas.

“I think the little red hat program is great because I honestly believe it starts with our babies,” Johnson said. “It has to start at the beginning for the mothers to understand, to be able to take care of themselves and be able to go to the doctors and get the proper treatment.”

Word of the program spread across Sonora, at Johnson’s church and among the volunteers of Community Hospital. By February 2016, the group had amassed about 1,500 hats—enough to keep warm the heads of most babies born in Southwest Texas for the month.

After a brief profile of the project appeared in the February 2016 issue of Texas Co-op Power, crafters from across the state responded with calls, letters and hats.

“It came kind of overwhelming at first because I didn’t plan for this to happen,” Johnson said. “I was just going to do a few hats and didn’t realize that this was going to literally snowball. I just started getting calls from everybody. Even husbands were calling, wanting their wives to do it.”

Now, the map of Texas in Johnson’s command center is littered with dozens of multicolored pushpins.

“I was getting the hats from so many different areas,” Johnson said. “And Jerry suggested, ‘Let’s get a map; let’s put the little pins on there, and then you can look back at ’em and go, wow!’”

“She’s a Friend From the Heart”

For Johnson, the stories poured in with the hats.

At 10, Ileana Baker, a granddaughter of one of Johnson’s Sonora friends, is the youngest hatmaker. She learned to knit in order to help, and now she has a shoebox full of tiny hats. Baker was born with two holes in her heart that affected her when she was younger.

“My mom noticed I was getting very hot and sweaty, and I wouldn’t eat, so she took me to my pediatrician,” Baker said.

Valerie Draper, 80, one of Johnson’s longtime friends, was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect some 18 years ago. Her father and brother both died of heart failure. She guesses she’s made some 200 tiny hats so far.

Blanc said congenital heart defects are the most common, about as prevalent as autism and many times more common than cystic fibrosis—“A lot of things that get a lot more press.”

Although not all congenital heart defects are fatal, it’s a big problem—and one that Johnson is fighting with big goals. She hopes to someday get a hat to every baby born in the state in February. Some 32,000 Texas babies are born every month, according to data from the Texas Department of State Health Services, but Johnson isn’t deterred. She expected to have 2,000 by the end of 2016 and hundreds more by February.

“I hope … we run out of hospitals, we run out of babies,” she said.

Most of Johnson’s hatmakers are retired women over 65, and most are electric co-op members. They all come to know and appreciate Johnson for her work, and she’s built a network of friends across the state.

“I can’t even begin to tell you how many,” she said. “I just love them all.”

They make the hats in groups around kitchen tables and alone with their thoughts in comfy chairs. They make them while they’re riding in cars, while they’re watching TV and while waiting in doctors’ offices. Some of them knit, and some crochet. Some spend days on every hat, and some can finish one in a couple hours.

They’re all making a difference.

Opal Powell of Shelbyville, a member of Deep East Texas EC; Aurora Hernandez of Seguin, a member of Guadalupe Valley EC; and Gina Fobbs of Centerville, a member of Houston County EC; exchange calls, photos and letters with Johnson.

Hernandez sends her hats off in batches of 50, some of which she makes while getting her monthly treatments at a cancer center in Houston.

Fobbs is a counselor at Federal Prison Camp Bryan. She introduced Johnson’s program to an inmate group called Beyond the Fence, which contributes to society from inside the women’s prison. They made 800 hats with donated yarn last year.

Powell puts her granddaughters to work making hats and still has the February 2016 issue of Texas Co-op Power on her living room table, open to the red hat story. She hopes to donate hundreds of hats by February.

“She’s a friend from the heart,” Powell said of Johnson. “I just love talking to her. She’s got a good outlook, and she’s got one good worker bee here.”

“This Has Touched So Many Lives”

Aaron and Lindsey Hockenberry didn’t know.

In April 2016 Lindsey got word that Londyn might not survive the day. The memory stayed with her.

“I saw the hospital’s number on my phone,” she said. “I can still feel the way I felt. You just get like cold. I was like, ‘Oh, no.’ ”

Now, Aaron and Lindsey Hockenberry know.

Londyn died that day. “It shouldn’t take somebody experiencing it for them to know about it,” Lindsey said.

With a lot of hard work and thousands of tiny, red hats, Nancy Johnson and her corps of knitters hope to help with that.

“This has touched so many lives,” Johnson said. “You cannot imagine.”

——————–

Chris Burrows is a TEC communications specialist.