Even though I was born and raised in Laredo, I did not know the background of what actually transpired during the boisterous Washington’s Birthday Celebration on the Juarez-Lincoln International Bridge each February. This birthday party, the largest of its kind in the U.S., drawing as many as 400,000 partygoers, had taken place annually since 1898—though it is canceled in 2021 for the first time.

During my early years, I would watch and work, selling bottles of water or cans of soda from an ice chest to make easy money. My family would go to popular events like the carnival and the Jalapeño Festival. The smell of deep-fried corndogs made me dizzy, and watching contestants eat jalapeños hand over fist troubled me, but I still looked forward to going. It gave us the same fun and novelty you find with hometown fairs everywhere.

When I began my academic career, I decided to study the spectacle surrounding Washington’s Birthday as a research project. I wanted to know more about the true meaning of this celebration. I wanted to find an explanation for why residents in Laredo and Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, continued to celebrate the birthday of George Washington, the first U.S. president, why that tradition persisted and why representatives from both countries hold on to the ritual of meeting on the international bridge. Out of that research came my book, ¡Viva George!: Celebrating Washington’s Birthday at the U.S.-Mexico Border.

One of the most challenging aspects of my years of research on both sides of the border was the search for the deeper significance of the idiosyncratic aspects of the celebration. I learned about the months of behind-the-scenes preparation and even participated in a horseback ride-along with Border Patrol agents to understand the origins of the event.

Paul Cox

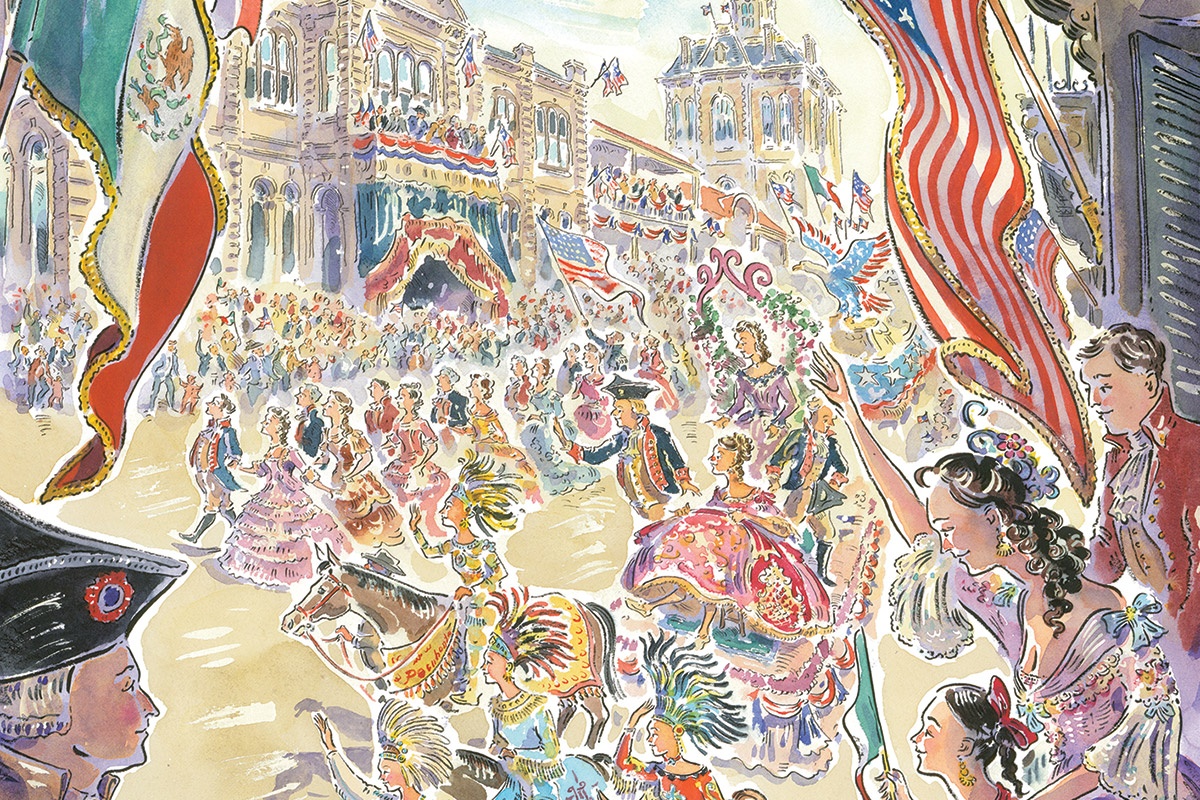

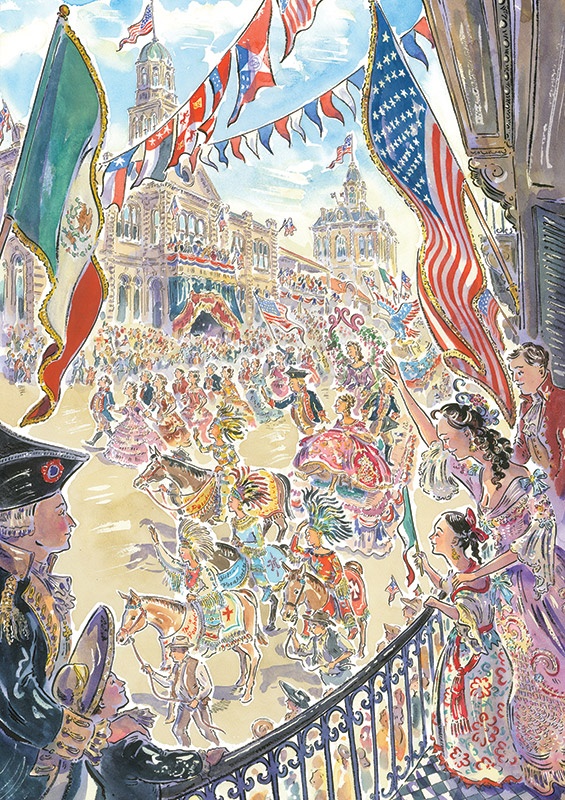

Originally organized and promoted by members of a white fraternity who impersonated Native Americans, the two-day festival included a reception in the middle of the international bridge, a reenactment of the Boston Tea Party, a grand parade culminating with Pocahontas receiving a key to the city and a pyrotechnic show advertised as “the greatest display ever seen in the State of Texas.” This cross-border tradition has changed over time, but the grand parade and the international bridge ceremony continue, and the event is still unapologetically ostentatious.

I had learned about the history and culture of Native Americans in school, but those lessons did not match up with the spectacle presented in Washington’s Birthday. “Playing Indian” is not appropriate. Rather than disparage those activities, I decided to use my research to understand the broader impact of the events.

Now the festivities include more than two dozen events in February, but the bridge ceremony is still the highlight. It includes abrazos—hugs—between celebrities and high-profile U.S. and Mexican politicians as well as actors portraying Washington and Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, the priest known as the “father of Mexican independence.”

These embraces are presented as evidence of how los dos Laredos, the two Laredos, have maintained cross-border ties, even during times of crisis.

In one important sense, the celebration is purely promotional, confirming the significance of international trade. As a researcher, I started asking basic questions about the legitimacy of the celebration. My research told me that it is less important to question the validity of the ideas behind the festivities.

I wondered if the ritualistic mythologizing of history could lead to any conclusion other than evidence that communities invent traditions.

Reading up on critical studies of nation and nationalism helped me take a big step back and figure out how to piece together the puzzle without expecting this border tradition to conform to any familiar national narrative.

In the course of more than a decade of research for my book, I learned that Washington’s Birthday Celebration has ensured positive media coverage for Laredo, solidified cross-border political and economic connections between the U.S. and Mexico, and even provided free and clear border crossing privileges to festivalgoers.

Studying the meaning behind celebrations changes how we think about national history and national heroes and helps us consider which heroes are worthy of veneration. Border enactments such as Washington’s Birthday are more than goodwill gestures because they challenge the perception of the border as a place only of violence and illegality.

Laredo native Elaine A. Peña is an associate professor of American studies at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.