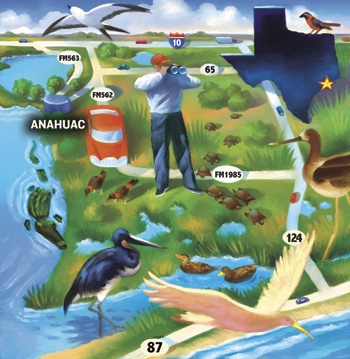

Beaumont likes to describe itself as “Texas with a little something extra.” West of the Louisiana border, The crumpled Texas map lay open beside me on the front passenger seat of the car. Just east of Houston on Interstate 10, I felt lost. Where, I muttered, is my exit? And then, there it was: Exit 810. Anahuac. I breathed a sigh of relief and turned south onto FM 563.

Six miles later, I was slowly driving through the little town, searching for the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge headquarters building, when a flash of movement caught my eye. I looked up and saw a hawk-sized bird, strikingly dressed in black and white, dipping and gliding like … a kite! A Mississippi Kite! But wait … this bird has a long, forked tail. It’s a Swallow-tailed Kite! Unbelievable. Five minutes in Anahuac—and still 15 miles from the refuge itself—and I’ve scored a bird for my life list.

I considered the kite a harbinger of the wildlife I’d see at the refuge and in nearby High Island, a migratory bird mecca. But reality tempered my optimism on this mid-April day: On September 13, 2008, the upper Texas Gulf Coast was pummeled by Hurricane Ike, a horrific storm that destroyed buildings at the Anahuac refuge, ripped up its roads and boardwalks and decimated its wildlife, including alligator, frog, salamander and turtle populations.

After meeting with Tim Cooper, manager of the Texas Chenier Plain Refuges Complex that includes the high-profile Anahuac refuge, I had a better snapshot of the situation: On the surface, things looked bleak. But the Texas coast has withstood hurricanes for centuries. Somehow, fragile ecosystems recover. And somehow, without maps or compasses, displaced animals find their way home.

“There’s mystery here, and you can participate in that,” Cooper says of Anahuac. “You can see things that you’re probably not going to see again.”

Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge

After massive repair work in the wake of Hurricane Ike, the refuge is now fully reopened and easy to find by following southbound FM 562 out of Anahuac to eastbound FM 1985.

For now, don’t expect to hear a chorus of frogs at dusk. And instead of seeing dozens of alligators sunning on the banks of canals, you might see five or six.

But something magical is happening here: In May, little brown turtles crossed FM 1985 in great herds, all marching south to the refuge as if they were one, driven by who knows what.

And yes, Anahuac, which offers them trees and wetlands, has birds. Lots of them. Possible fall sightings range from Tricolored Herons to American Avocets to Mottled Ducks, year-round residents here. And if you’re really lucky, you might see American or Least Bitterns, secretive masters of camouflage that freeze in place with their bills pointing up to resemble the reeds in which they’re hiding.

Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, (409) 267-3337, free admission, www.fws.gov/southwest/refuges/texas/anahuac/index.html

High Island

High Island is just that—a high island, and small community, surrounded by salt marshes. At more than 30 feet above sea level, it’s the highest point on the Gulf of Mexico between Mobile, Alabama, and the Yucatán Peninsula.

Thanks to its height, the island dodged the brunt of Ike’s storm surge and remains, at least in my mind, the Holy Grail of Texas birding.

The birding is fantastic all along the upper Texas coast. “We’re probably the birdiest place in all of America,” says Winnie Burkett, sanctuary manager for the Houston Audubon Society, which owns four sanctuaries on High Island, an 18-mile drive from the Anahuac refuge on eastbound FM 1985 and southbound Texas Highway 124.

But in the spring, there’s no place like High Island, where the sanctuaries and their big trees serve as five-star hotels for migrating birds exhausted from their 600-mile flight across the Gulf of Mexico.

You’ll see the most binoculars raised at the Louis Smith Boy Scout Woods Bird Sanctuary, where birders crowd the grandstands overlooking Purkey’s Pond. But come back for fall migration: Birds aren’t wearing their bright spring colors, making identification more difficult, but you can still get good looks at flycatchers, warblers, tanagers and orioles.

Also this time of year, egrets, herons and White Ibises return at dusk to roost at the Smith Oaks Bird Sanctuary rookery. And there’s nothing like the spooky sight of alligators inhabiting the sanctuary, sharing space with wading birds.

And in a fall ritual, thousands of migrating hawks fill the sky at nearby Smith Point and the Candy Cain Abshier Wildlife Management Area on the eastern shore of Galveston Bay.

High Island sanctuaries, (713) 932-1639, open daily from dawn to dusk, $5 donation covers admittance to all, www.houstonaudubon.org

——————–

Camille Wheeler is staff writer for Texas Co-op Power.