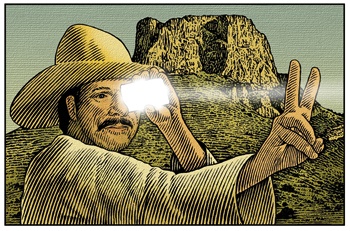

When I’m lucky enough to be in the Big Bend region, I sometimes think I catch a flash of light out of the corner of my eye. It could be anything: imagination, a glint off the corner of my glasses or something else. Put me in another landscape, and I might not even notice or imagine this almost subliminal flash of light. But Big Bend is, or at least was, the land of avisadores.

Before the telephone or even the telegraph, in the Hispanic culture of Mexico and the American Southwest there were the avisadores, people who specialized in communicating over vast distances by using a mirror or another shiny object to reflect the sun and use it to flash avisos—messages—to other avisadores, who passed the word along. Essentially, this might have been the world’s first wireless communication device.

The Aztecs probably used the same method of long-distance communication. Montezuma knew within minutes when Cortez landed near Vera Cruz, nearly four days away. Other, later civilizations, including the Plains Indians, used smoke and mirrors to communicate over long distances.

At any rate, communicating with mirrors has been around a long time, and it’s nice to think it might still exist, thus the hopeful curiosity I feel if I think I see light flashing across those vast distances.

Well into the 20th century at least, avisadores would flash breaking news to other avisadores who somehow knew to be looking for a message, or else picked it out of thin air. The nuts and bolts of the system has always been a mystery.

Photographer and writer W.D. Smithers wrote in Chronicles of the Big Bend (re-issue, Texas State Historical Association, 2000): “Probably the most outstanding features of the avisadores are their secrecy and their wide distribution,” he wrote. Smithers learned as much as an outsider probably could learn about the avisadores by living and working among them.

Avisadores were sending messages for Smithers in the early 1930s. During his many forays into the isolated mountains, canyons and deserts of West Texas, he often found meals or fellow travelers or friendly locals waiting for him when he arrived at a way station or destination.

Even though the avisadores were secretive about their craft, the avisos they sent were not privileged information. Like the Internet, the concept behind the avisos was democratic. You only had to know the codes. Still, the whole business has retained an air of mystery to outsiders.

“Perhaps the most mysterious and inexplicable aspect of this aviso business is how avisadores know when an aviso is being sent their way,” Smithers wrote. “Avisos gave no warning of their arrival, but I have seen many avisadores look up, change directions, or drop whatever they were doing to read them. Some sixth sense seemed to tell the avisadores when avisos were on the way.”

The avisadores and their avisos show up, sometimes coincidentally, in other writings about the Big Bend area. In Patricia Wilson Clothier’s memoir about growing up on a ranch in Big Bend before it became a national park (Beneath the Window, Iron Mountain Press, 2003), she wrote about the difficulty of selling the last of the family’s livestock after her father, Homer Wilson, died. The daunting task was made more frustrating by the fact that they were at least a couple of workers short of being able to get the work done efficiently.

But on the day of the livestock sale, men walked out of the hills above the ranch, ready and able to work.

“One of the Mexican workers must have flashed a message to [the village of] Santa Helena, but none of the hands claimed credit,” she wrote.

Maybe knowing about all this makes my imagination merge with wishful thinking. Even if the message system were still used, the odds of my seeing an aviso flash across the Chihuahuan Desert or through the high passes of the Chisos Mountains would be mighty long.

But I’m still going to take note if I see or think I see a special flash of light out there. A lot of people who are a lot smarter than I am told me I would never see a mountain lion either. I did, but that’s another story. The lion first revealed itself to me as a flash of light, headlights reflecting off the animal’s eyes. I’m no avisadore, but I got the message.

Clay Coppedge frequently contributes to this magazine.