It was not long after reading Black Beauty for the first of many times that I had a dream that one day I would have a place which would embody everything Black Beauty loved about his final home. [That] would be a place where animals would do whatever they wanted to do, not what people wanted them to do, and particularly not what people wanted them to do when they were watching them. It would also be a place that the animals felt, from the day they arrived, belonged to them, and would always belong to them as long as they lived.

Cleveland Amory

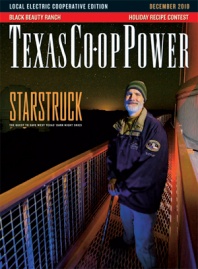

Ranch of Dreams

——————–

Riding in an all-terrain utility vehicle through a ranch in East Texas, I met more genuine superstars than one would ever find in Hollywood.

One after another, I encountered them discreetly going about their business in the rolling hills of a landscape as perfect as paradise. Right there before my eyes were Babe the elephant, Omar the camel, RooRoo the kangaroo, Wilbur the hog, Friendly the burro, and many other diverse and amazing beings.

They are among the more than 1,200 domestic and exotic animals of 50 species that live here at the almost 1,300-acre Cleveland Amory Black Beauty Ranch—the largest and most diverse sanctuary in the world for rescued, abused and neglected animals. I don’t call them “superstars” because of their physical beauty or any ability they might have to perform, entertain or please—but rather for their unique life stories of suffering, their dramatic rescues and their remarkable ability to forgive.

Though some ranch residents were the victims of deliberate abuse, most of them suffered at the hands of previous owners who exploited them for profit and/or pleasure. The animals have been rescued from zoos, circuses, trophy-hunting ranches, breeding ranches, biomedical research projects, the exotic pet trade, slaughterhouses, public lands and more.

A considerable number of them were rescued in Texas. However, many of them were transported from elsewhere, as were the 84 starving and neglected wild mustangs that arrived here last year from Nebraska (14 of the mustangs remain on the ranch). This large-scale equine rescue helped inspire the new Doris Day Horse Rescue and Adoption Center, expected to open at the ranch early next year, said Diane Miller, director of the Black Beauty Ranch north of Murchison, near Athens.

“The most rewarding thing is when you see animals come in from a horrible background–for example, a cruelty case, physically and emotionally damaged–and you’re able to work with them to regain their trust,” Miller said. “To see them live in a protected environment where their needs are met and they’re free to behave exactly as they wish, where they’re able to be who they’re born to be, it’s the best job on earth.”

It Began with a Book

On an average afternoon at Black Beauty Ranch, the animals can be found huddling under shade trees, gliding across peaceful ponds, grazing in silky grass and basking in the sun.

They might appear at first glance to have uneventful lives, but if they could talk, they would surely tell you some stories. Indeed, I only understood who these ranch dwellers were, and a bit about their incredible sagas, because I read about them in a book by the late Cleveland Amory, the famous author and animal advocate who founded Black Beauty Ranch in 1979.

In Ranch of Dreams: The Heartwarming Story of America’s Most Unusual Animal Sanctuary—published in 1997, the year before Amory’s death—he tells the riveting story of how his dream for the ranch, and the ranch itself, came to be. As the book explains, Amory’s concern for the welfare of animals developed when he was a boy growing up in Boston and was nurtured by a beloved aunt who took in many stray dogs and cats. His aunt gave him Anna Sewell’s 1877 classic children’s book Black Beauty about a carriage horse who is passed from one owner to the next and mistreated before finding happiness in his final home. The book changed Amory’s life.

“It was not long after reading Black Beauty for the first of many times that I had a dream that one day I would have a place which would embody everything Black Beauty loved about his final home,” Amory wrote in Ranch of Dreams. That, he wrote, “would be a place where animals would do whatever they wanted to do, not what people wanted them to do, and particularly not what people wanted them to do when they were watching them. It would also be a place that the animals felt, from the day they arrived, belonged to them, and would always belong to them as long as they lived.”

His impetus to realize that dream came in 1979, when Amory learned that the National Park Service planned to kill hundreds of wild burros living on public land in the Grand Canyon. Private sheep and cattle ranchers had claimed the burros were competing with their livestock for food, and the plan from federal officials was to shoot the burros from the air.

Amory and the organization he founded in 1967 to help animals, The Fund for Animals, also had a solution involving helicopters, but theirs was to airlift burros, one at a time, in a sling and deliver them to safety. Their two-year rescue of 577 burros from the Grand Canyon succeeded, necessitating a new home for the animals—hence the birth of Black Beauty Ranch in East Texas.

Since then, the ranch, served by Trinity Valley Electric Cooperative, has taken in several other types of animals, too, including chimpanzees, bison, horses, prairie dogs, iguanas, turtles, rabbits and more.

One of the ranch’s most popular celebrities whom I had the privilege of meeting was Babe, an elephant and 14-year ranch resident whose recent death set off a continuum of online commemorations from hundreds of admirers. As a baby, Babe witnessed the killing of her mother in South Africa. Babe was shipped in a crate to America to work in the circus, Cleveland wrote, “and it was in the crate that, we were told, she not only banged up two of her legs so badly but also, as evidenced by her head, had tried to commit suicide.”

Perhaps the most famous of the ranch’s residents was the late Nim Chimpsky, known around the world as the first “talking chimpanzee.” Raised by a researcher in a human family, Nim studied sign language under researchers and teachers. After several years, “Project Nim” ended, and Nim was slated for a laboratory where he and other chimpanzees would be the subjects of hepatitis vaccine research. After what Nim had done for people, Amory viewed such a move as absurdly unfair and negotiated successfully not only for Nim to come to Black Beauty Ranch, but also for a female chimp named Sally Jones to move with Nim. The pair became best friends at the ranch, and each lived there well into their senior years.

Tears of Sadness and Joy

In 2005, the Fund for Animals formed a partnership with the Humane Society of the United States, which oversees the Fund for Animals and the fund’s ranch, which has 15 full-time employees.

In keeping with Amory’s wishes for the ranch to be a home—not a zoo, circus or other entertainment venue—visitors are not allowed on a daily basis. However, the ranch holds open houses for the public each fall and spring.

Before you visit the ranch, I urge you to read Amory’s Ranch of Dreams. Otherwise, you will not know where you are once you arrive, or who each of the creatures are that you’ll have the opportunity to meet. My family and I read it together, taking a section of the book each night, and were shedding tears of sadness and tears of joy by the end of the first chapter. We’ll never view any venue that exploits animals for human entertainment in the same way again.

Black Beauty Ranch is where Cleveland Amory’s dream came true, and if you believe as I do that animals, too, have dreams, the ranch is a dream come true for every animal who, after years of neglect, years of abuse, years of being whipped to perform tricks or run faster, finally finds this place where they are simply free to be.

A sign at the ranch gate welcomes new residents with a quote from the last lines of Sewell’s Black Beauty: “I have nothing to fear; and here my story ends. My troubles are all over, and I am at home …”

——————–

The Cleveland Amory Black Beauty Ranch is open to the public only on spring and fall open-house days and during special events. For more information, visit http://blackbeautyranch.org or www.humanesociety.org/blackbeauty or call (903) 469-3811.

Staci Semrad is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.