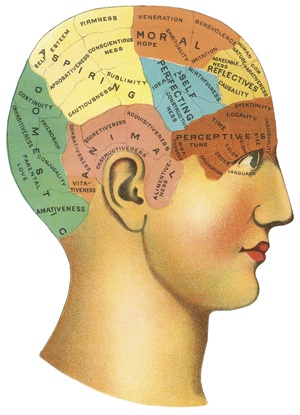

You need to have your head examined.” If we only had a dollar for each time we’ve heard that, right? But have you ever wondered where the phrase originated? Some folks track it back to the antique pop psychology movement called phrenology. Phrenologists believed that the brain consisted of some 37 separate physical “organs” and that each organ was responsible for a different “mental faculty” or “propensity.”

By phrenologizing an individual—examining the shape and size of his or her skull—the phrenologist could purportedly ascertain virtually everything about the person’s character. Traveling “professors” of phrenology, or craniography, testified that humans could change the size and shape of the brain’s organs through exercise, minimizing undesirable tendencies while developing more positive character traits.

Imported from the Old World, phrenological thought reached the young Republic of Texas by at least as early as 1838, when the bodies of two hanged murderers were exhumed so the bumps on their heads could be examined.

Sam Houston was phrenologized by a blind “professor” in Washington, D.C., in 1849. (Perhaps that’s why the Sam Houston Memorial Museum in Huntsville offers phrenology demonstrations by special request.) Many early Texans relied heavily on their phrenological charts when making major life decisions, and employers sometimes consulted a bump doctor about a prospective employee’s character. A blind phrenologist told Matagorda County native Charles Siringo, author of the classic 1885 book A Texas Cowboy, that his “mule’s head” would serve him well as a detective, sparking his career with Pinkerton. Around 1870, an 18-year-old farmhand named Isaac T. “Ike” Pryor submitted his cranium to a traveling phrenologist named Fowler in Austin (no known relation to this writer; the New York firm of Fowler and Wells was the nation’s leading phrenology publishing and education firm). “Mr. Fowler felt all the bumps on my head and … wrote something on a piece of paper, and said that would be $10,” Pryor told C.L. Douglas, author of Cattle Kings of Texas, decades later. “I paid over the money, three-quarters of a month’s salary, and read the paper. It said: ‘All your life you will be under the influence of some woman.’ ”

Somehow, that enigmatic prophecy spurred Pryor to quit the farm and take to the trail on cattle drives. As he related to Douglas, Pryor, who became a cattle baron, was still so enamored of bumpology 60 years after his own examination that he was trying to convince Dean Kyle at Texas A&M University that “before he gives those boys diplomas … , he should have their heads felt of … then put it down on the diploma what every boy is best fitted for in life.”

Sometimes a phrenological analysis proved uncomfortable. When Dr. O.S. Fowler—who might have been the same phrenologist who examined Pryor—examined James Dickson Shaw, pastor of the Fifth Street Methodist Church of Waco, at a public meeting in 1880, he pronounced the minister an agnostic. Church officials then questioned Shaw’s orthodoxy and demanded that he surrender his credentials for views “detrimental to religion and injurious to the church.”

Two of the most active Texas phrenologists, professor William Windsor and his wife, Madame Lilla Windsor, operated a phrenology parlor in Gainesville. The professor exhibited his collection of skulls at the Texas State Fair in 1890, pointing out to fairgoers the telltale bumps and ridges that supposedly indicated one was capable of murder. In a weeklong stand at San Antonio’s Casino Hall in 1892, professor Windsor offered lectures on “Phrenology, and how to Read the Characters of Men,” “How to Become Rich,” “How to Be Healthy and Handsome” and special programs for men only and women only.

Though the head-case craze had lost much of its allure by the time the professor died in 1923, Madame Lilla Windsor continued offering phrenological services from her home in San Antonio until her death in 1934. The Windsors believed that phrenology could be employed for matrimonial success. At an 1886 phrenological party in McKinney the professor examined the heads of young ladies and gentlemen and then paired them off. The Dallas Morning News said it was “one of the most enjoyable affairs of the season.”

Still, even in its glory days, the beguiling science of bumpology sometimes failed to convert a skeptic. In 1887, when professor Windsor launched the Bridal Wreath, a monthly magazine devoted to the “science of phrenology and its application to matrimony,” another scribe for the Dallas newspaper opined, “If the crop of idiots is large this year, the Bridal Wreath will be a success.”

——————–

Examining the lively side of medical history, Gene Fowler’s books include Mystic Healers & Medicine Shows.