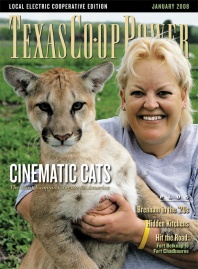

The most famous cougar in the American entertainment industry, a female named Kasey, lives in the Texas Hill Country. In fact, pretty much every cougar you see on TV or in the movies is Kasey.

Kasey is the official cat of Puma, the athletic shoe maker. (Puma, by the way, is one of as many as a hundred different names by which cougars are known—they’re also mountain lions, panthers, catamounts, Tennessee wildcats, mountain screamers and painters.) Kasey was the cougar in “Talladega Nights.” She is known as the gentlest, safest cat in the movies.

In a popular Chevy Colorado commercial, Kasey plays tag across a western plain with a guy in a pickup. She has appeared with Brett Favre in a deodorant commercial and Demi Moore in a sports drink commercial. She has acted in “Flicka,” “The Arc” and “Where the Red Fern Grows.”

Kasey lives at the Lone Star Wildlife Ranch near Geronimo, owned and run by 44-year-old identical twin sisters Jamie Ruscigno and Jewels Satterfield. They believe that constant prolonged human contact, including nighttime cohabitation, is the best way to socialize big cats. For the past 11 months, Jamie has shared her bedroom with three young cougars named Austin, Dallas and Houston. Last summer they were kittens; now they are 80-pound, 3-foot-long teenagers.

“You cannot take a cat to a movie set and work it unless you have an incredibly strong bond with that cat,” Jamie told me when I visited the ranch recently. “That takes months and months of being with that cat 24/7. The first thing I did after I got the cougars was refinance my house, because I knew what it was going to take.”

The Lone Star Wildlife Ranch sits on 10 acres northeast of Seguin. Structures take up little of the acreage, leaving most of it open. Green hills surround it in all directions.

Jamie explained her immersive style of training to me as we were walking from the one-story traditional frame house in which she and Jewels live to a complex of big-cat cages, which hold Kasey, the three boy cougars (in the daytime), and two Bengal tigers, Asia and Riah.

A large, high-fenced arena in which the cats can run freely adjoins the cages. Jamie and Jewels also have a herd of 17 show goats, for sale to Future Farmers of America students, two Great Pyrenees to protect the goats, five rescued dogs, and a rescued, housebroken goat named Stewart.

“The second I got around a big cat on a set, it just grabbed my heart,” Jamie said. “I just always wanted to be around them. They’re so wild. All their instincts are still there. They can be persuaded not to act on them by tons of love, but you have to be watching for those instincts every second of every day.”

Riah was the only cat visible as we approached the cages. Jamie walked up to the edge of her cage, to within conversational distance, as if she were approaching an acquaintance at a party. Riah weighs 500 pounds. She can run 35 miles an hour. She was lying on a waist-high platform in her cage, looking at us. Riah’s fangs were hard to comprehend. She could easily have taken my entire head into her mouth. In her lucent gorgeousness, she was like a drug. The bewitchment of a tiger at that range is unconditional. Its close presence invites you to visualize your own death, and its beauty is absolute in the way of a sea anemone or the moon.

She chuffed—an exaggerated lippy exhalation that Jamie said was a tiger’s way of saying hello. Jamie encouraged me to chuff. I did. It seemed like patently human mimicry, but Riah looked at me with lovely indolent amicability and chuffed right back.

In the cage behind Riah’s, Asia got up and started pacing and growling. She began talking to Asia familiarly, but Asia roared several times in consternation. The word “roar” is helpless to convey the sound she made, which was so granularly deep and massive it was hard to imagine it came from an animal. It was closer to a subterranean-earth sound. Evolution designed it to banish every immediate threat a tiger might face, and Asia’s roar seemed to permanently alter the environment. Once a tiger roars someplace out in the uncaged world, it is always there.

Jamie and Jewels moved to Texas from Los Angeles in April 2005 after 20 years in the film business as animal trainers and producers. They left mainly because they realized they liked animals a lot better than Hollywood people.

Jamie and Jewels chose Texas because they were raised in the Wenatchee Valley, in central Washing-ton state, which is populated almost entirely by Texan, Oklahoman and Arkansan migrants who arrived in the 1930s and ’40s after Dust Bowl crop losses and oil industry collapses.

“We grew up Southern as Southern can get,” Jewels told me. “All our family was from Texas.”

Jamie and Jewels are no-nonsense and outspoken and laugh easily, and they possess a kind of forbearing, lightly fatigued generosity that probably has to do with living almost exclusively for a group of exquisite, hard-to-satiate animals.

After I saw the tigers, Jamie and Jewels took me to see Kasey, Austin, Dallas and Houston. The glamorous Kasey, after squeak-chirping, which is the incongruous cougar way of saying hi, came gliding low-bellied out of her house and lay down to be scratched. Jewels got down and scratched her. She began to purr. It was exactly like the purr of a housecat through an amplifier. Cougars, Jewels said, are the largest purring cat. The bigger ones all have a bone in their throat that causes them to roar.

“Cougars act just like big housecats,” Jamie said. “They can be super-aloof, super stuck-up, super-playful. They’re the laziest cats. Eighty percent of what they go after, they kill. They’re so good at it they don’t have to do a lot of work.”

Cougars stalk and spring selectively. They may follow their prey for 10 miles. They are fast and startlingly agile. From a standstill, adult cougars can jump 12 feet straight up into the air and 15 feet forward. They can leap off 60-foot cliffs and land unhurt. In flight, they remain perfectly balanced. They can pause in midair and change direction. Their tails, as long as their bodies, act as stabilizers and rudders.

Behind Kasey’s cage, in the arena, Austin, Dallas and Houston were mock-stalking and mock-pouncing. Jamie and Jewels have watched them leap, turn their bodies into quasi-sails by arching their backs and spreading their arms, and rotate 90 degrees in the air before landing.

After we’d watched the boys for a while, I asked to see the master bedroom Jamie shares with them.

“Oooh, it’s really bad right now,” Jamie said. The cougars were outgrowing the space.

She and Jewels keep their house nicely furnished and well maintained, except in certain zones. We went through the kitchen to get to the master bedroom. A thawing block of chicken necks filled one sink basin, and a 5-pound package of ground chicken, also thawing, filled the other. The cats on the ranch collectively eat 42 pounds of meat a day: 1,260 pounds a month, 15,300 pounds a year. “Everything we do is to feed the cats,” Jamie told me.

The master bedroom was pretty trashed. The cougars had chewed up the windowsills, paw-printed the wall mirror over the bathroom sink, pulled down the closet racks, torn and eaten blankets and pillows, and tail-daubed the inside of the door with brief, vertical, high-up streaks of mud that would be completely unidentifiable if you didn’t know where they came from.

Jamie plans to keep Austin, Dallas and Houston in her bedroom for another month. “The longer they can keep that tight mama bond,” she told me, “the better they’ll be when they grow up. In the wild they live with their mom sleeping in their den for up to two years.” They sleep soundly through the night, and they purr with increasing softness before they fall asleep. Jamie sleeps well. She has a lot of cougars in her dreams.

——————–

Jeff Tietz has written for Rolling Stone, The New Yorker and Vanity Fair, among other publications.