Dear Mrs. Wentworth:

You don’t know me. But I think I knew your grandfather. That is, if I have the right Mary Wentworth. …

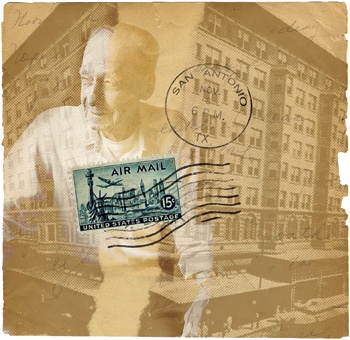

Thoughtfully, I penned a few more paragraphs, then signed my name and addressed an envelope. After scouring the Internet, my high-tech search had finally ended. A special friendship that unfolded long before email and cellphones might finally find closure via a postage stamp.

Cedric Noble and I crossed paths in downtown San Antonio in February 1979. Nearly a lifetime separated us. Barely 20, I was a journalism student, determined to expose the “corrupt” managers of a run-down hotel. He was old and gaunt, crossing a street in front of me. He glared at me when I dared to ask if he’d ever stayed at the hotel. “Yeah,” he replied gruffly. Could I call him? “Yeah.”

It turned out that Mr. Noble had indeed rented a room at the place I was investigating, but it had been 40 years ago. After we spoke, I could have tossed away his phone number. Instead, I called him a week or so later. “I don’t give a damn about anyone,” he told me, “and no one gives a damn about me.” I listened. I asked how he was. Then I said I’d call again, which I did. Regularly. Gradually, he softened.

Mr. Noble shared little about his past. I knew he was born in Chicago. He’d had a daughter with his first wife but left them after returning from World War I. He never told me why. His second marriage lasted many years. But eventually, it ended, too. His third marriage was tumultuous and short. Well past the age of 80, he’d ended up in San Antonio, alone and with little to his name.

Several phone conversations into our friendship, I suggested lunch at a diner not far from where he lived in a 1920s hotel called the Robert E. Lee. At other times, we ate breakfast out. I ran errands for him and grocery shopped when his supplies ran low. One afternoon, I brought my 35-millimeter camera, and he agreed to a photo session. While Mr. Noble talked, laughed and reflected, I snapped pictures of him seated in a worn chair next to the window of his dingy room. I treasure those black-and-white images.

While at home on summer break, I called him weekly. “Hey, how are you gettin’ on?” he’d ask. Fine, I’d say. We’d chitchat but never for long. At 87, Mr. Noble’s health was failing, and he tired quickly. After we hung up, I knew he’d shuffle back to bed and listen to the news or maybe a ballgame on his transistor radio.

In May 1981, I graduated from college and moved home. Six weeks later, I married. Though busy with a new husband and newspaper work, I worried about Mr. Noble some 150 miles away. Could I move him to our town? Should I make other living arrangements for him? I didn’t know. But I kept calling.

A time or two, I drove to San Antonio to visit him. When he went into a veterans hospital in March 1982, I made a special trip. Feeble and groggy, Mr. Noble’s sunken eyes lit up when I sat down by his bed. “How’s the old man?” he asked, referring to my husband. I smiled, took his thin hand in mine and fought back tears. Then I told him that I loved him.

A few days later, the phone rang at 2 a.m. “Mr. Noble just passed away peacefully,” the doctor gently said. “You left instructions to be notified.” After thanking him, I hung up and cried. My dear friend was gone.

I’d been told that if no one claimed his body, he’d be buried in a pauper’s grave. My husband accompanied me back to San Antonio so I could sign the paperwork that authorized a military funeral. Among Mr. Noble’s few belongings, I found letters I’d mailed him, bundled with string.

In July 1988, my mother and I located Mr. Noble’s grave at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio. With her Kodak Instamatic, she photographed me and my toddler son, Patrick Noble Rodgers, by his gravestone. At the cemetery office, I left my name and address, hoping that someday his family might find me.

Through the years, I never stopped hoping. But I never had the tools to search myself. Until I sat down at my computer last March. Little by little, I traced Mr. Noble’s family tree. Amazingly, I contacted Betty and Ann, two great-nieces by his second wife. Ann mailed me pictures of Mr. Noble as a child, teen, soldier and dapper older man. She also sent an antique locket with two photos—a dashing Cedric in his 20s and a young girl wearing a white bonnet. “That’s probably his mother, but we’ve never known for sure,” Ann told me.

Since talking, we both now believe the unidentified child was Mr. Noble’s daughter. After hours of online digging, I finally found her—Miriam Noble Clements Stilling. I also learned that several years after Mr. Noble left, Miriam’s stepfather adopted her. In 1937, she married Kenneth Stilling. In 1989, Miriam passed (just seven years after her father). Were there any children? I held my breath and ordered copies of obituaries. Yes, she’d had two daughters!

I’d never know one daughter, Laura Stilling. She passed in 2002. But Mary Wentworth still lived in Albuquerque, and I’d found an address. That is, if I had the right Mary. …

Ten days after I mailed my letter, the phone rang. “This is Mary Wentworth. I got your letter, and yes, you have the right Mary.” Stunned, I sat down. “My sister and I always wondered what happened,” she continued. “No one ever talked about my grandfather. Thank you for being so kind to him.”

“Oh, thank you,” I began, blinking back tears. “You see, I’d always hoped I could someday tell his family that I knew Cedric Noble … and that I loved him, too.”

——————–

Sheryl Smith-Rodgers is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.