If you haven’t visited your local public library lately, now is the time. What you find may surprise you. This is especially true in rural communities.

Take the Silverton Public Library in the Texas Panhandle, a half-hour drive east of U.S. Highway 87 between Amarillo and Lubbock. There, across from the historic Briscoe County Courthouse, stands a former Masonic Lodge built in the 1950s, which, after extensive renovations, reopened in mid-2015 as a model 21st-century library.

Step inside and you’ll find a hive of activity rather than a hushed and dusty quiet zone. Seniors and students alike occupy the well-lit rooms, relaxing in comfortable chairs, scanning freshly installed shelves filled with books or taking advantage of the high-speed wireless Internet at computer terminals.

“Before, we had a tiny room in the basement of the courthouse,” says Tina Nance, one of the 25 volunteers who devote their time to operating the Silverton library. “Nobody used it. But with this new building, the new books and new computers, we are seeing a real increase in people coming in.”

The lively scene at Silverton is repeated across the state, says Patricia Smith, executive director of the Texas Library Association, which has 7,000 members representing all kinds of libraries, from small collections to large public institutions. “The modern library is a little bit of everything,” she says. “In these small towns, they are the intellectual hub, community center and a major resource for social services.”

As such, Smith says that rural libraries could not have a better friend these days than the Austin-based Tocker Foundation, a family-run nonprofit. Providing financial assistance to libraries in towns with fewer than 12,000 residents is chief among its philanthropic efforts. The renovations in Silverton, for instance, were paid for with grants from the Tocker Foundation, one of several nonprofit groups in Texas that provide financial support to the state’s libraries.

“The Tockers have been an inspiration,” Smith says. “They are true visionaries and agents of change, and they have given rural libraries real hope. In its way, the Tocker Foundation is every bit as powerful as the Carnegie Foundation. Their help with technology, especially, is helping these libraries to be the very best they can be.”

Darryl Tocker, the foundation’s executive director and nephew of founder Phillip Tocker, says the desire to help small-town libraries grew directly out of his late uncle’s own experiences growing up as the son of immigrant parents near Waco. Young Phillip Tocker learned to read and write at the local library and eventually uncovered resources for filing property contracts and managing bankbooks—skills he taught his mother and father. “He learned all that with the help of librarians, and he wanted to give back,” Tocker says. “He did not necessarily believe in entitlements, but he did believe that with unfettered access to information, anybody could achieve anything they wanted.

“We build collections, but we do a lot more,” Tocker says. “We are helping cut down on the digital divide, solving a lot of connectivity issues for people who don’t necessarily have broadband access in their homes. In some cases, we even have permission to beam Wi-Fi into the parking lot so that the library doesn’t have to be open. There will always be a need for books, but a lot has to do with the patron experience.”

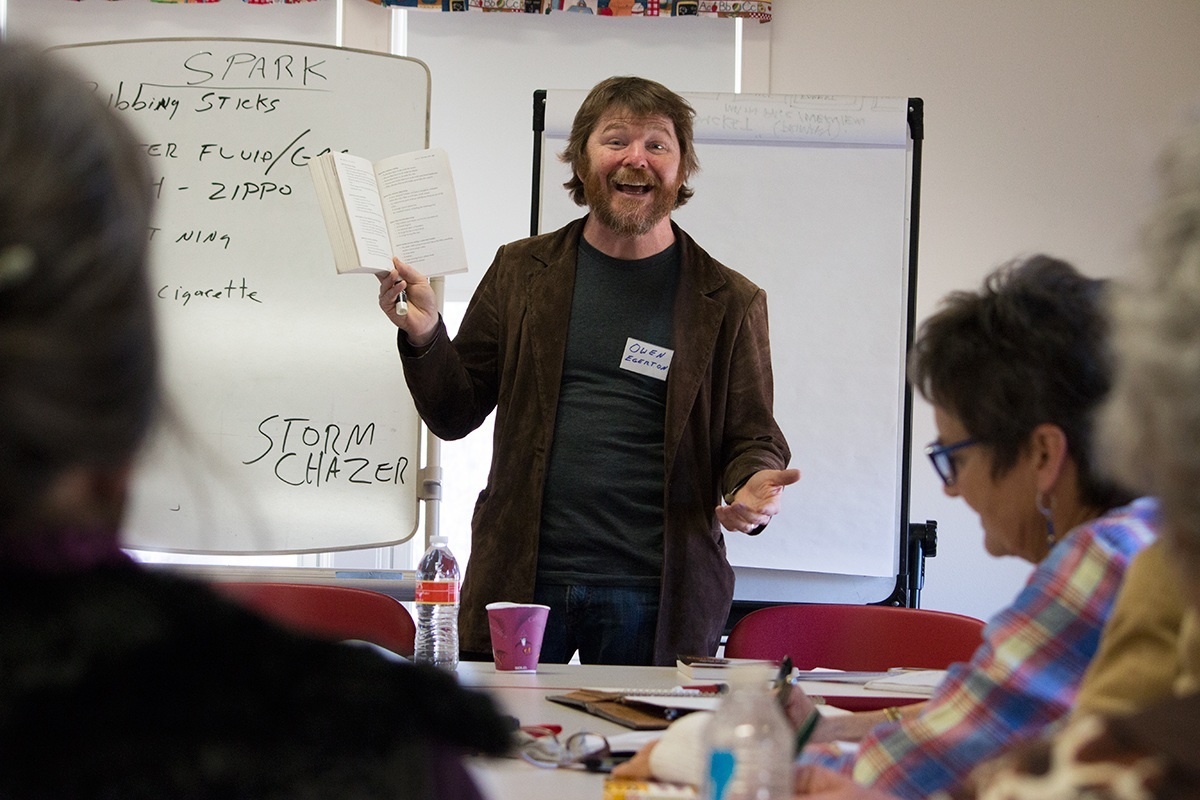

Texas Writes, a program from the Writers’ League of Texas, brings published authors to small-town libraries statewide for half-day seminars on topics that include memoir writing, memorable dialogue and improving productivity. The Tocker Foundation also supports Texas Writes. “The purpose of the program is for us to connect with writers across the state,” says Becka Oliver, WLT executive director. “In these communities, the library is often the place where you find the writers, and we have people checking our website for events and driving 30, 50, even 80 miles to be there.”

In 2015, Texas Writes ushered writers to 30 rural libraries, paying a stipend to the authors for their time. “It’s so rewarding for us to go into the libraries and see what they’re doing,” Oliver says.

The Tocker Foundation’s biggest individual library grants run to $50,000, and the foundation encourages applicants to aim high with their requests so they can make a greater impact. As many as 350 libraries are eligible statewide, says Karin Gerstenhaber, Tocker grant director.

“The more rural it is, or the more remote it is, the more important it is as a community anchor,” says Gerstenhaber, noting that many small-town libraries double as community centers, not just offering an educational setting for youths but also providing employment resources and skills training for adults, and in some cases, even health screenings. “The goal is to update them for 21st-century use.”

Additional organizations aid small-town and rural libraries in Texas. Tocker paid for a new drop box at the Bonham Public Library northeast of Dallas and provided grants for computers and tablets that brought the staff’s electronics suite up to date. However, Bonham has also received grants from the Ladd and Katherine Hancher Library Foundation in Columbus. The foundation, which serves communities of fewer than 50,000 people, bought furniture to replace the 1970s décor at Bonham. The MW and Fair Miller Foundation in Bonham provided $13,000 for the library to buy four child-friendly computers loaded with educational games and featuring touch-screen displays that aim to help kids ages 2 to 12 prepare for school and get a leg up on classwork. “Before, we were just maintaining the status quo,” says Kimberly Bowen, Bonham’s library director. “Now we are a bustling community center—and business center. Our patrons are very excited.”

Tocker Foundation grants provided a lifeline for the Pottsboro Area Library, which occupies a former post office not far from Lake Texoma. Just a few years ago, says Dianne Connery, volunteer president of operations, Pottsboro faced a budget shortfall that could have meant the library’s demise. “It looked like what it was, an old 1960s post office, and the only people who came here were seniors who wanted large-print books,” Connery says.

Today, the online calendar includes an old-school video game night with first-generation console games and a celebration of World Juggling Day. “With the help of the Tocker Foundation, we were able to reinvent ourselves,” Connery says, noting that the Tocker monies acted as a magnet for other grants.

“We bought new furniture and got another grant from the Hampshire Foundation for new shelves. And we were able to buy new desktop computers and tablets, and now teens and tweens all hang out here, too. The Tockers are our cheerleaders,” she says. “They are such strong supporters, we feel like we can go to them anytime we have a new idea.”

That explains why the grants have been used not only for electronics, stylish renovations and plush furniture to draw more library visitors, but also, in some cases, upgrades to infrastructure. Installing e-books and automated circulation systems means that librarians don’t have to track which books are overdue, who owes fines or what volumes remain on the shelves. The Tocker Foundation initiated a program for uploading old newspapers and microfiche systems to the Internet, creating a vast database of historic news reports that might have disappeared without small-town libraries, which have kept the papers. “The libraries are frequently the last repository,” says Gerstenhaber, noting that as more newspapers fold, this information is endangered.

It’s all part of fulfilling a vision that Phillip Tocker first had in the 1960s, says Darryl Tocker. After graduating from the University of Texas at Austin in the 1930s and then earning a law degree, Phillip Tocker became a powerful lobbyist and made a fortune in billboards and outdoor advertising, which led him to the presidency of the Outdoor Advertising Association of America. By 1992, the Tocker Foundation—which also underwrites the Texas Reads license plate program and backs the annual Texas Book Festival—turned its energy to helping rural libraries.

“My uncle felt he had taken a lot of money out of these small towns,” explains Darryl Tocker. “Helping the libraries was his way to repay them.”

——————–

Dan Oko is a Houston writer; his website is danoko.com.