Editor’s note: Jim Dent is the author of Courage Beyond the Game: The Freddie Steinmark Story, a biography of The University of Texas football hero scheduled for release in August 2011 by St. Martin’s Press. Dent, a New York Times bestselling author of The Junction Boys: How Ten Days in Hell With Bear Bryant Forged a Championship Team, previews Steinmark’s biography in this story written exclusively for Texas Co-op Power. To read more of Dent’s work, see the “Mighty Mites” feature from our December 2009 issue for a story about the legendary Masonic Widows and Orphans Home football team.

——————–

Of all the players in the glorious history of University of Texas Longhorns football, the late Freddie Steinmark remains one of the most loved and revered. “In his short time at Texas, Freddie became a hero,” current Longhorns Head Football Coach Mack Brown wrote in the prologue to Courage Beyond the Game: The Freddie Steinmark Story, a new biography of the hard-hitting safety whose heroic story riveted the nation. “Not necessarily for what he did, although he was a fine player, but for who he was.”

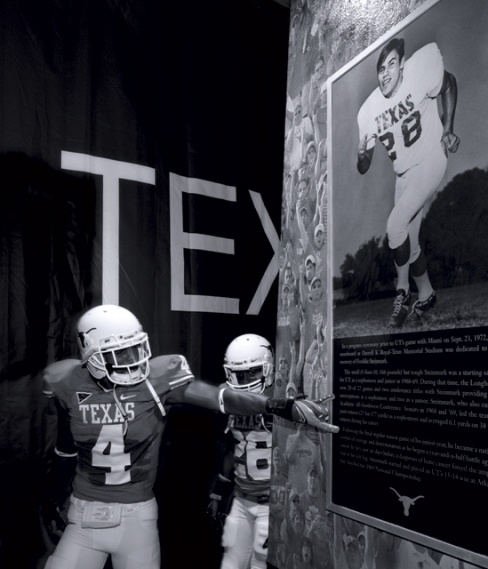

It’s little wonder that two large photos of Steinmark adorn the walls of the tunnel leading to the field at Darrell K. Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium in Austin. Just seconds before charging onto the turf before games, each Texas player touches one of the photos with the Hook ’em Horns hand salute.

It is one of the university’s most respected traditions.

Coming out of high school and enrolling at The University of Texas (UT) in the fall of 1967, Steinmark provided an underdog story that touched every heart. Not a single big-time football program recruited the feisty scatback in spite of his selection for the Denver Post’s Golden Helmet Award as the best high school scholar/football player in Colorado. That was before Coach Darrell Royal studied film of the diminutive Steinmark and decided to take a chance.

Royal dispatched Assistant Coach Fred Akers on a fact-finding mission to Steinmark’s hometown of Wheat Ridge, Colorado. Akers knocked on the door, and a slight youngster greeted him with a big smile. Akers actually thought it was Steinmark’s younger brother, Sammy, six years his junior.

On his recruiting trip to Austin, Steinmark wore high-heeled cowboy boots, hoping he would look taller. He stood 5 feet, 9 inches and weighed 150 pounds.

When he sat down on the other side of Royal’s long oaken desk, he could barely believe what the coach said.

“Son, let me tell you something very interesting,” Royal said. “I didn’t get to the University of Oklahoma until I was 25 years old because of the war. I was just about your size. I quarterbacked the Oklahoma Sooners to a national championship one year. On defense, I broke the record for interceptions. I don’t care how big you are.”

That day, Steinmark committed to UT and made a vow to himself that he would start every game. He did not care how high the odds were stacked. When Steinmark arrived for fall practice, sophomore rover Mike Campbell mistook him for a team manager.

“The kid looked like he was 15 years old,” Campbell recalled.

That was before Steinmark was issued a uniform and began knocking freshman teammates all over the field.

Playing for the Yearlings (the freshman team’s mascot) during an unbeaten five-game schedule, Steinmark led the Southwest Conference (SWC) in interceptions with four. During a 45-0 victory over Texas A&M University in the season finale, Steinmark returned a punt 76 yards for a touchdown.

Everything was clicking for the young man with the warm smile and bright, sparkling eyes. He strolled the campus with his blonde-haired, blue-eyed girlfriend, Linda Wheeler, whom he had dated since the eighth grade. Freddie was making good grades, attending Catholic mass on a regular basis and living the ideal life.

On the first day of preseason drills in 1968, Steinmark replaced Scooter Monzingo at safety on the varsity defense. It was rare when Royal opened the season with a sophomore in the starting lineup, but Steinmark, with his speed and agility, offered the perfect antidote to some of the country’s best passing attacks, which were popping up all over the SWC. (The conference was formed in 1914 and disbanded in 1996, with four of its members—UT, Texas A&M, Texas Tech University and Baylor University—uniting with the Big Eight Conference to create the Big 12 Conference.)

The Longhorns began the 1968 season raggedly, tying Houston and losing to a mediocre Texas Tech team. But with James Street replacing Bill Bradley at quarterback, the wishbone offense began to roll in the third game against Oklahoma State. The Longhorns won eight straight games en route to 18-wheeling Tennessee 36-13 in the Cotton Bowl, finishing the season as the third-ranked team in the national Associated Press (AP) poll.

The start of the 1969 season generated enormous hope. America’s sporting press trumpeted Texas as a possible national champion, and the ABC television network persuaded Texas and Arkansas to move their mid-October game to December 6 with the prospect of playing for the collegiate title on national TV.

Steinmark was named to the preseason All-SWC team. But he had developed a limp, and the Texas coaches were keeping an eye on him. The hitch in Steinmark’s gait had first been spotted that summer by his boss at a car dealership in Denver. Then his dad, Fred Steinmark, noticed him running unevenly during conditioning sprints.

In the early part of the season, Steinmark tried to hide his pain. Finally, Akers insisted that he undergo treatment from team trainer Frank Medina. He initially diagnosed the injury as a charley horse that would heal in time. Steinmark limped his way through the season, intercepting only one pass.

Both Arkansas and Texas rolled through the season with nine straight wins. The Horns and Hogs were ranked 1 and 2, respectively, in the AP Top 20 poll for the “Big Shootout’’ in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Steinmark was limping so badly in pregame warmups that his friend, Bill Zapalac, began to call him “Ratso,” the gimpy, third-rate con man played by Dustin Hoffman in “Midnight Cowboy.”

The Texas coaches considered benching Steinmark before recognizing the extent of his contributions during the 18-game winning streak. In spite of his limp, Steinmark remained a savvy coverage man, never letting a receiver past him. Plus, when tackling, he packed a sledgehammer wallop.

The Shootout

December 6, 1969, was cold and drizzly in Fayetteville. Almost every seat in Razorback Stadium was filled more than an hour before kickoff, and President Richard Nixon was in attendance.

Steinmark was limping badly.

Arkansas built a 14-0 lead through three quarters. But two Texas miracles were coming: Street opened the fourth quarter by splitting the Arkansas defense and sprinting 42 yards for a touchdown. He also scored the two-point conversion. With six minutes and 32 seconds left to play, he completed a 43-yard pass to Randy Peschel on fourth down to set up another touchdown. Jim Bertelsen’s 1-yard touchdown run and Happy Feller’s extra-point kick made it 15-14.

That deficit was almost erased on Arkansas’ next possession. The Hogs targeted Steinmark on a post route by Chuck Dicus. The little safety showed a huge amount of gumption, grabbing the All-America wide receiver as he ran past him. The holding penalty moved the Hogs to the 7-yard line—but they did not score. Three plays later, Steinmark’s gamble paid off as UT’s Danny Lester intercepted quarterback Bill Montgomery at the goal line, killing the scoring threat.

At the final gun, the pain finally died in Steinmark’s leg. Numbed by the excitement and the adrenaline, he danced with his teammates along the sideline. Then he took off running at full speed for the dressing room. When he came upon teammate Steve Worster, he asked, “Why are you crying?”

“No, Freddie,” Worster replied. “Why are you crying?”

Tragic News

Three days later, Steinmark finally confessed his pain to Royal. The coach sent him for X-rays, and a few hours later, Steinmark learned he might have a tumor at the tip of his left thighbone. He was flown to Houston’s M.D. Anderson Hospital, and a biopsy was scheduled. Royal caught the next flight back from New York, where his team was receiving the MacArthur Trophy as the national champion. He paced the hospital’s hallways, repeating the same phrase. “I can’t believe this is happening.”

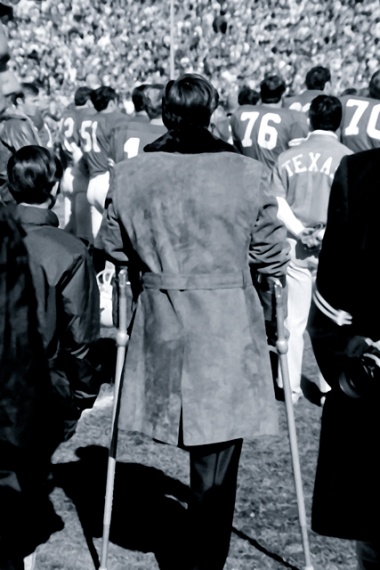

The biopsy revealed that Steinmark had played most of the season with almost an inch of his femur devoured by cancer. The leg was amputated at the hip. But Steinmark was not about to be beaten by osteosarcoma, a malignant bone tumor. He was up and walking on crutches within a few days, and soon announced that he would stand on the sideline during the Longhorns’ Cotton Bowl matchup with Notre Dame.

Nineteen days after the operation, he crutched down the long Cotton Bowl tunnel to a standing ovation. He saw his team rally in the fourth quarter once more to defeat the Fighting Irish 21-17.

Twelve days later, he walked across the stage on a shiny new prosthetic to receive his letter jacket from Royal. There was not a dry eye among the 6,000 fans at the Austin Municipal Auditorium.

Steinmark’s life in the next few months became a whirlwind of change. One night at a restaurant, he broke up with Linda, telling her: “Linda, I might not make it. You, on the other hand, have a long life ahead of you. We are going to live two different lives.”

He moved into the Catholic rectory on the east side of town. He drove his first car, a brand-new blue Grand Prix. He learned to play golf and water ski on one leg, visited Nixon in the White House, grew his hair out, and even started drinking beer for the first time.

By the fall, he was missing Linda so badly that he asked her to come back. They were walking across campus one day when Freddie spit blood on the ground. Linda rushed him to the hospital, and soon he was undergoing painful chemotherapy treatments for lung cancer. With his hair falling out, Steinmark asked his friend, Texas offensive tackle Bobby Wuensch, to shave his head in front of the entire team as a form of “hazing” for becoming a freshman coach. Steinmark, who had been named a coach by Royal, did not want the team to know his condition was deteriorating.

Over the Christmas holidays, Freddie and Linda went to see “Love Story,” the movie about two Harvard students, Jennifer Cavalleri (played by actress Ali MacGraw) and Oliver Barrett IV (Ryan O’Neal). In the movie, Oliver marries Jenny, and she is soon stricken with deadly leukemia.

Before seeing “Love Story,” Freddie and Linda knew nothing about the storyline. Thus, they were rendered speechless at the end. Standing outside in the falling snow, in Denver, a tearful Freddie said, “We just watched our future.”

A few days later, in spite of his bleak condition, Freddie proposed marriage. Rings were purchased and a date of May 23, 1971, set for the wedding. Linda sewed her own dress, and Freddie bought a white Italian suit for the wedding. Invitations went out.

But the wedding was called off: On May 23, Freddie was beginning to slip in and out of a coma. He died on June 6, 1971, and the funeral held in Denver drew the largest crowd in the history of the state.

The glorious life of Freddie Steinmark spanned 22 years, five months and nine days. On the morning he died, he was a national symbol for courage. His great friend and teammate Tom Campbell compared Steinmark to Notre Dame legend George Gipp, who died at the age of 25 and is considered by some to be the greatest all-around player in the history of college football. “Freddie,” Campbell said, “was George Gipp without all of the hype.”

Or, as former trainer Spanky Stephens summed up: “Freddie gave us a road map for life.”