Dropping my shovel to catch my breath and gulp down a bottle of water, it occurred to me that the simple-seeming matter of digging a hole in the ground is actually a fairly deep subject. Pondering the matter while taking a break, I realized there’s a “hole truth” to be learned about digging that applies to everything from planting trees or burying deceased pets to the search for hidden treasure.

Back in the early 1950s, I dug my first modest hole in a limestone-walled flower bed in front of my grandparents’ limestone veneer house in what then was far North Austin. Using a garden trowel, I began mining for what I confidently believed to be nuggets of white gold—in reality, small limestone rocks mixed in with the topsoil that had gone into the built-in planter.

Grandmother tolerated my excavations as long as I didn’t disturb her elephant ears, though she did caution me that if I dug too deep, I’d end up in China. While that might have been quite an adventure for a 6-year-old, and would have opened wonderful trade opportunities with the Asian market, I never made it to the other side of the globe.

I dug my first sizable hole when my mother attended Texas Woman’s University in 1957. The site was in the vacant lot next to the duplex in which we lived on the outskirts of then small-town Denton. My motivation for this hole was not the prospect of gold, but keeping up with my fellow kids. With the Hula-hoop craze yet to hit North Texas, the neighborhood boys occupied themselves by digging a deep “fort” in the reddish-tan soil adjacent to the alley behind our duplex.

What got me into a hole was the one the big kids had dug. With multiple diggers, they had excavated a big square in the ground deep enough and wide enough in which to stand and play. They then covered it with boards and mounded dirt on top. A kid-wide trench half as deep served as the entranceway. They had created an Old West-style dugout that could have doubled for a tornado or fallout shelter—a great, albeit potentially dangerous, place to play cowboys and Indians.

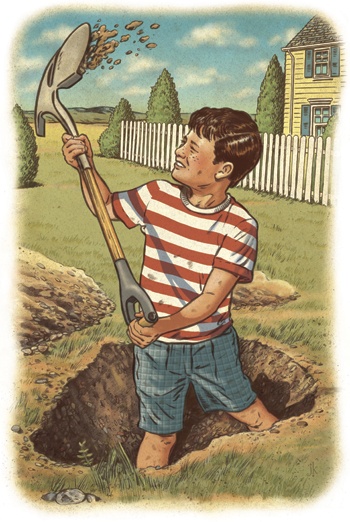

Naturally, I wanted my own dugout. But being only a second-grader, I didn’t have much success. The hole I managed to dig went down only 2 or 3 feet, barely deep and wide enough for me to crawl into, even if I really scooched up.

One reason I never had any luck digging a hole deep enough to stand up in (I have, however, dug myself into some really deep holes in the figurative sense over the years) is because wielding a shovel is plain hard work.

Now, way too old to play in backyard dugouts without causing a considerable amount of talk, I’m occasionally reminded of the extent of physical labor involved in digging a hole as I lay pets to rest, or, on a more upbeat note, plant trees.

Recently, I had occasion to force a shovel blade into the sod once more, this time to bury an old roll of tar paper. I hunt on a small tract of land along the San Gabriel River in Williamson County north of Austin. Over the past several years, I’ve been working to restore the property to its natural state by removing trash that has accumulated on it.

I’ve burned or hauled off a lot of old lumber and junk from the place, but a long-discarded roll of tar paper stuck out like, well, an old roll of tar paper lying in an otherwise pristine outdoor setting. I didn’t want to burn it, knowing that wouldn’t be good for the atmosphere, and I didn’t want to tote it all the way to town, especially not after I found a big bull snake in the cannon-like mouth of the roll.

Finally, with the help of my hunting buddy, Stephen, we developed a plan. Once the snake found another place to hang out, we would place the heavy roll in a wheelbarrow and roll it down a rocky hill to the black dirt-rich flood plain. There, I would dig a hole and bury the eyesore.

It had rained about a week before, so I figured the spadework would be easy. But when I pushed the shovel into the ground, my right knee reminded me why I had gone into journalism instead of manual labor. Finally, with a fair amount of effort, I dug a hole about 1 foot deep and 3 feet long.

“You know,” I joked to Stephen as he stood watching me work, “I have renewed respect for old-time well and outhouse hole diggers. Digging is hard work.”

Seriously, those last four words explain why most Texas treasure tales—beguiling as they are—are merely folklore.

One of the most enduring Texas folktale categories involves a pack train laden with, depending on the teller and location, either Spanish, Mexican, Confederate or French gold. Indians attack, and to escape, the teamsters are forced to bury their loot.

Think about it. Digging a hole big enough to hide a treasure chest full of gold would take a lot of work. Dodging arrows would make the task even more difficult.

I’ll keep digging holes when I absolutely have to, but what little treasure I own is “hidden” in a stainless-steel safety deposit box in our nice, air-conditioned bank. All I have to dig for is the key in my pocket.

——————–

Mike Cox is a frequent contributor to Texas Co-op Power.

Editor’s note: Call 811 or visit their website before you dig to avoid hitting underground utility lines such as electric, gas, cable and phone.