Texas’ rural veterinarians wear their work.

In Pecos, fresh green cow manure, a souvenir from a local dairy farm, clumps on Dr. Ronald Box’s baseball cap above his ear.

In Gustine, Dr. Lisa Willis is elbow deep inside a heifer’s rump, probing the animal’s uterus to find out if she’s pregnant. Willis’ arm-length latex glove catches most of the heifer’s digested waste. The rest, as Willis slowly extracts her arm, goes on the clinic’s floor.

In Junction, Dr. Larry Brooks is docking the tails of two lambs. Blood pools on Brooks’ cowboy boots, spatters the stripes of his dress shirt and smears with the mud on his jeans. He doesn’t notice his soiled clothes until an assistant points out his appearance.

Brooks shrugs. “This is pretty common,” he says. “It’s what you get.”

Make no mistake: The life of a rural veterinarian is romantic in notion only. For the men and women providing medical care for our state’s large animals and livestock, there’s no such thing as a uniform (clean or not) day.

Judging by their thinning ranks, the mental, emotional, physical and financial toll of their jobs is wearing them out—and scaring off many younger veterinarians who prefer the more comfortable and predictable lifestyle of the city. Typically saddled with enormous debt upon college graduation, often more than $100,000, they’re heading to urban areas for higher salaries and better hours.

But debt is just one culprit for a critical shortage of rural veterinarians nationwide that’s being acutely felt in Texas. As the state’s population shifts from predominately rural to mostly urban, so does its veterinarian work force. The result is what some are calling a misallocation of country doctors that’s leaving farmers and ranchers in remote parts of the Panhandle, South Texas and West Texas with no licensed veterinarian to call for help.

For those Texans who have no idea what rural veterinarians do, here’s a look at three who do it all. They deal with death, disease, injury and emergencies every day. But trade careers? No way, they say.

‘It’s me by myself. Like, completely by myself.’

Veterinarian: Dr. Lisa Willis, 39

Location: Gustine

College: Graduated from Auburn University’s College of Veterinary Medicine in 2005 with about $130,000 debt ($123,000 of that amount remains).

The sorrel filly hit the dirt with a thud.

As sedatives raced through the horse’s body, Willis ran her hand over the animal’s right hind leg. There was no doubt it was injured. The quarter horse, a 2-year-old named Tonto, had probably gotten tangled up kicking in her pen.

The real question was whether Tonto could be saved.

Digital X-rays revealed a fractured hock and, worse, a dislocated patella. Willis kneeled beside the unconscious horse in owner David Pattillo’s indoor corral, near Hamilton, and tried to coax the injured bone into place. She massaged the thigh, then mashed it. Nothing.

She shoved with all her weight as her intern, Stetson Posas, a senior at Tarleton State University who’s interested in pursuing a veterinary pharmaceutical sales career, held Tonto’s leg by the hoof and tugged. Nothing. She tried again with the leg bent at different angles. Still nothing. Willis and Posas traded places, but the patella wouldn’t budge.

Willis informed Tonto’s owner of his options: costly, invasive surgery that might leave the horse crippled, or euthanasia.

“It’s up to you,” she told him.

It was a Monday in August. At the time, Willis had been in business for about a year and a half. Before opening her own practice in Gustine, near Comanche and northwest of Killeen—and buying on credit a $32,000 hydraulic chute, a $50,000 portable X-ray device and other equipment—she had worked in an Austin-area animal hospital. In Gustine, she’s found a niche treating buckin’ bulls and regularly does equine work.

Someday, Willis said, she hopes to bring a partner onboard to open the first state-of-the-art referral hospital in her area. When she does, neighboring ranchers and horse owners will no longer have to drive an hour and a half for major surgeries on their livestock.

“Right now,” though, she said, “it’s me by myself. Like, completely by myself. I’m the receptionist and the technician and all that.”

As Tonto lay in the dirt, Willis waited for Pattillo’s answer. He sighed and smiled ruefully. Of the 40 or so horses in his herd, Tonto wasn’t one of the gentle ones.

“Well,” he said, “just put her to sleep.

Willis retrieved a large, pink syringe containing a lethal dose of barbiturates from her pickup. The procedure was over in minutes.

“Did she go?” Pattillo asked.

“Yeah,” Willis whispered. “Yeah, she died.”

The veterinarian caressed Tonto’s sleek, golden-brown neck. “Sorry, mama.”

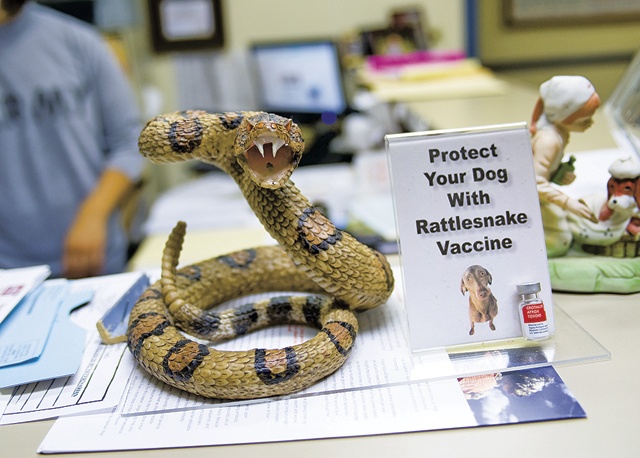

‘I do everything except snakes.’

Veterinarian: Dr. Larry Brooks, 60

Location: Junction

College: Graduated from the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences in 1975 with about $4,000 debt (college debt has been erased).

One time, Brooks was trying to castrate an unbroken stud horse when it kicked his thumb right off. “Got that put back on,” he says.

Another time, an angry bull knocked him over, crushing two vertebrae in his neck. And he suffered a herniated back disk when a 350-pound buck sheep hit him from behind. He’s 60 years old. How long can he keep this up?

“Till I fall over dead,” he says. “I love it.”

Brooks has silver-gray hair, and tobacco flecks his teeth. He’s the sole veterinarian in Junction and Kimble counties, on the western edge of the Hill Country. Money’s been tight, and the past 31/2 decades haven’t been kind to his body. But Brooks isn’t complaining. Other vets have had it tougher.

“Most of us have been beat up one way or the other—run over, kicked, stomped, drug—if we do it long enough,” he says.

It’s a Wednesday in August at Brooks’ clinic. It’s not even lunch time, and already he’s frozen a cancerous skin tumor on a cow’s eyelid with liquid nitrogen; prescribed medicine and advice when a deer breeder burst through the door and hollered, “I got a pen full of yearlings sick”; shown a woman how to set a trap for feral cats; and docked the tails of two lambs being groomed for livestock shows. When he showed up to work this morning, a bag of sheep feces was hanging from the doorknob. No note. No label. In his lab, he diluted the dung with water to check for parasites, which resembled tiny footballs under his microscope.

“I do everything except snakes,” he says. “Worked on giraffes last week. If you drag it in here or call me, I’ll come try.”

Now he’s fielding a call from a rancher. “So you’ve got a dead calf,” Brooks barks into the phone.

A steer has died mysteriously in the night, and the rancher wants to know if Brooks should perform an autopsy.

“It’s up to you,” the vet says. “Not gonna bring your calf back.”

An hour later, Brooks is standing inside a little corral made of hewn cedar posts. His afternoon autopsy is lying in the hot summer sun. Brooks and the rancher chain the carcass to a tractor and drag it to a patch of shade. Brooks slices open the calf and digs out the heart. He examines it and turns to the rancher: “You’re vaccinating.”

“When?” the rancher asks.

“As soon as you can.”

The heart is covered in speckles of blood, indicating the calf died from blackleg. The disease spreads through feed or forage that has been tainted by a bacterium called Clostridium chauvoei. Without vaccinations, more calves could be dead within days.

“Let’s do it quick,” the rancher tells Brooks.

“Yeah, let’s do it tomorrow,” the veterinarian replies. “We’ll run ’em through as fast as we can shoot ’em.”

‘A veterinarian never knows where he’s going or what he has to do.’

Veterinarian: Dr. Ronald Box, 57

Location: Pecos

College: Graduated from Texas A&M in 1985 with $5,000 debt (college debt has been erased).

From his clinic in this dusty West Texas town, Box roams a stretch of desert as vast as some states. He leaves for work most mornings when the stars are shining.

He might drive 70 miles south to the Davis Mountains, 100 miles northeast to Midland, 150 miles west to Fort Hancock, or 140 miles north to Lovington, New Mexico.

He only schedules one ranch call a day: “A veterinarian never knows where he’s going or what he has to do.”

Half of his job is the treatment of beef and dairy cattle. One early morning in August, he tested more than 200 head of dairy cattle for bovine tuberculosis. He was back at his clinic by 8 a.m.

Later that morning, Box was spaying a dog when a young cowboy in a ten-gallon hat walked in unannounced through the back door. The cowboy said his horse had been snakebitten, but another couple was already waiting for Box to finish the spay so he could examine their dehydrated mare. The cowboy said he’d come back in a little while.

Then a different client, from Fort Stockton, 50 miles to the southeast, rolled in with a dead calf in the back of his pickup.

“We told him to be here after lunch,” said Box, exasperated, as he stitched up the dog’s belly.

“Well,” his assistant replied, “he’s early.”

Box figures he could earn the same pay if he shuttered his clinic to eliminate overhead costs and just worked at dairies and ranches. But he can’t do that. Too many people—and their animals—rely on him.

Box started an intravenous drip in the mare’s neck. He took a quick look at the stillborn calf, its hair wet and matted, and gave the same diagnosis he’d given over the phone: It was the mother’s first pregnancy, and the calf got stuck in the birth canal. It happens. When the cowboy came back, Box determined the horse wasn’t snakebitten. It was a puncture wound on the horse’s knee. The prescription: penicillin and frequent flushing.

Box works 60 to 70 hours a week, but today was extra busy because one of his assistants was on vacation, and he lost his son to high school football practice. Nathan, a junior at Pecos High School, hopes to attend veterinary school at Texas A&M and follow his father into the practice.

“He could possibly be through in 10 years,” Box said. “I’d be 68 years old. If I can last that long, I can give it to him.”

——————–

Wes Ferguson is a freelance writer based in Northeast Texas. Camille Wheeler is associate editor for Texas Co-op Power magazine.