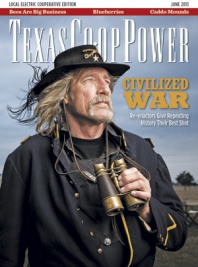

A light breeze pushes the acrid smell of battle across a couple hundred acres of rolling prairie on Mosser Longhorn Ranch outside Midway in Madison County on a cool, drizzly, winter Saturday afternoon.

A glance at your cellphone tells you it’s February 2013. A glance at the horizon tells you something much different.

To the left, on a small hillock beneath a handful of mesquite trees, is a Union cannon, flanked by a company of blue-clad infantry and nine cavalry troopers, their horses snorting and pawing the mud. Ahead, in the distance, is another line of soldiers. Hues of gray, tan, brown, blue and even a dash of red are visible after the smoke from their rifles clears. To their right is a 10-pound Parrott rifle, what passed for a weapon of mass destruction 150 years ago, pulled by four horses and accompanied by cavalry.

A yellow nylon rope separates fantasy from reality. You and about a hundred curious spectators stand behind it, a figurative foot in two centuries. Beyond the rope, there’s only one. For those men, women and children, it’s 1863, and the American Civil War is in full fury.

Out on the line, Union Maj. Howard Green cracks a smile beneath his flowing moustache and shouts to his men, “You guys know we win today, right? Yeah we win today, but tomorrow they kick our butts.”

On this overcast afternoon, the gray may rule the sky but the Blue will win the day.

That’s the rewarding thing for re-enactors: Lose today; win tomorrow. Take a shot in the chest today, live to fight again tomorrow. Re-enactors don’t care so much who wins—well, some do—as much as getting it right. That means eating, sleeping, drinking and fighting like they did in the Civil War, without cellphones, wristwatches or any other modern conveniences.

You find this land that time forgot after you arrive in the early morning fog about 11 miles off Interstate 45 and park your vehicle near the red pickup with the Stars and Bars sticker emblazoned with the slogan “Fighting Terrorism Since 1861.” You walk past the tents of sutlers selling modern food and drink and souvenirs and enter a row of tents, horses picketed on paths of straw, and campfires. Unlike some hardcore re-enactments, the Midway event is a family affair, so women and children—dressed as camp followers, color bearers and even soldiers—are alongside the men.

Halfway down on the left is the camp of Lt. Billy Blow of the 8th Texas Mounted Cavalry. While his wife, Carolyn, in a striped print hoop dress and bonnet, bakes bread, Blow prepares for combat. Wearing wire-rim glasses and the weary look that befits him as one of the event’s organizers, Blow, 63, is bent over a trunk, loading a massive Walker Colt .44 revolver.

Blow, a member of Houston County Electric Cooperative, knows there’s a trick to loading firearms of the period, particularly muzzle loaders. Without a projectile to hold back the powder, the re-enactors need a substitute. They use a lump of Cream of Wheat wadded together with water.

“We in the cavalry call it ‘the breakfast shot,’ ” he quips.

Sounds harmless. Blow sets a can on the ground, points the pistol toward it, yells “fire in the hole,” as you’re supposed to when discharging a firearm in camp, and pulls the trigger. The can flies as if hit with a baseball bat.

Re-enactors began arriving on Friday to set up. It’s chilly and wet, so they’re in winter camp. Some enjoy the relative luxury of a cot, some only a wool blanket on a patch of soft grass. At a large-scale national event, such as the 150th Gettysburg this summer, which a smattering of this group will be attending, you’ll see the entire spectrum, including re-enactors who’ll just sleep wherever they stop, with only a blanket of stars.

“You might start off sleeping on the ground,” says Col. Randy Cohen, 50, whose job as advertising photography manager for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram kept him from participating in the Midway re-enactment but who talked about his re-enacting through that most marvelous of 20th century innovations, the cellphone. “When you get older, have kids, your back gets stiffer and you move up. You go to a pup tent, and then a wall tent when you become an officer. Rank has its privileges.”

They’ll eat what the soldiers then ate, healthy servings of hardtack (a tough, flat, bland cracker) and beans with the occasional treat of chicken and dumplings and beer bread cooked in a Dutch oven. At Midway, one unit was roasting a pig they’d killed earlier in the week.

They fire the same weapons, wear period uniforms made from the same wool and canvas as the real soldiers wore and fight with the same tactics. They’ll soak a brass button in urine for a few weeks to get it to look aged. While most will wear brogans or a pair of boots from the era, some will fight barefoot, just as great-granddad did.

Sometimes they’ll spend weeks choreographing a 15-second saber-tomahawk fight scene to get it so perfect that an EMS crew will end up breaking it up, fearing someone is being hurt.

When it comes to realism, though, Texas re-enactors face a problem that those in most Southern states don’t. There weren’t many Federal forays into Texas—Galveston, Port Lavaca, Indianola, Brownsville, Laredo, Corpus Christi and Sabine Pass, plus an attempt by way of the Red River—which means there isn’t much to faithfully re-enact. So they improvise. The Battle for El Camino Real wasn’t a real event, but everything else—with the notable exception of the portable toilets beyond the camp—is straight out of the Civil War.

It’s a time that obviously pulls at the souls of the 150 or so re-enactors on hand. Like any hobby, re-enacting draws from a predictable pool of candidates. Most are men, though units like the ones in Midway also include women as nurses, camp followers and even combatants; and children as flag bearers, drummers and camp aides. Many are history buffs, keen on the Civil War. Some are military veterans; some are gun enthusiasts; and some are horsemen and horsewomen.

Many say they have kin who fought in the war. Dennis Partrich, chaplain of the 36th Texas Dismounted Cavalry, says he has relatives from Alabama listed on the surrender rolls from Appomattox. Cohen, commander of the 36th, claims his stepfather’s bloodline stretches back to Union Gen. Alfred Terry, the man whose orders Gen. George Custer disobeyed on the way to a date with infamy at Little Big Horn.

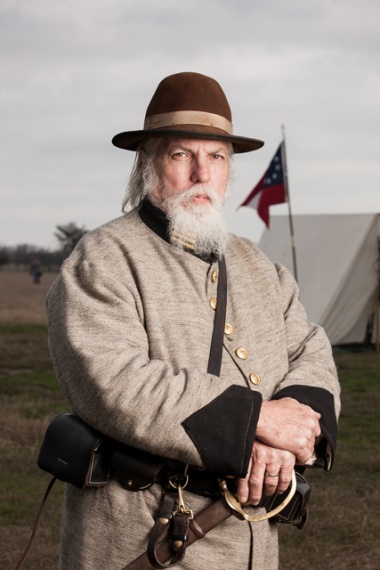

Some just came as spectators and loved it. Dyson Nickle, 49, who wears the charcoal gray wool coat of the commander of the 3rd Mounted Cavalry, sleeves festooned with braiding, went to an event 20 years ago a volunteer paramedic and left a re-enactor. “So I escaped from work into the 19th century,” he says. “I loved it right away.”

“If nothing else, we see ourselves as amateur historians,” says Partrich, an adjunct instructor at Dallas Baptist College. “A lot of us guys like to burn powder, but we also like to honor the memory of those who fought in the Civil War, Blue and Gray.”

To balance perspective, and the ranks, all re-enactors are required to have two uniforms, one from each side. As a Confederate, the mutton-chopped Nickle portrays Patrick Edward Peabody, who dies at Bentonville, North Carolina, about an hour before Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrenders in one of the last engagements of the war. As a Federal, Nickle, a counselor at Stephen F. Austin University, plays a random officer of a New York Cavalry unit who would remain in Texas during Reconstruction.

Most re-enactors are around age 40 and up—no surprise because it takes awhile to acquire the necessary equipment, different for each side, and it’s not cheap. A replica jacket can cost upwards of $150. The gear almost $200. Accurate period boots go for $150. A period rifle can set you back $800. A full 10-pound Parrott cannon, complete with caisson and rigging, as Col. Johnnie Holley of Douglas’ Texas Battery has carried, has a replacement value of $40,000

Such an expensive hobby has its downside. Holley, a member of Upshur Rural Electric Cooperative, won’t be making the trip to Gettysburg because toting the full rig, including horses, is just too expensive. “It would take three diesel trucks to pull everything,” says Holley, 78, a retired Delta pilot. “I wish we could afford it, but we can’t.”

Money is just one of the factors that decides what kind of re-enactor one becomes. Commitment and attention to detail are also important.

There are three types of re-enactors—the Farbs, the mainstream and the stitch counters. The Farbs—a term apparently derived from the German word for color (Farbe)—are the casual re-enactors who capture the spirit, if not the authenticity. They might wear boots that aren’t like the ones worn in the 1860s or uniforms of inaccurate colors (hence the Farb nickname), but they help place the joy in participation.

The mainstream are more serious, striving for accuracy but not demanding it. Close is good enough.

Most re-enactors, like ones in Midway, seem to fall between this category and the hard core.

Known as stitch counters, hard-core re-enactors crave absolute accuracy in gear and tactics. When at a re-enactment, they are always in character and attire. Did the Texas units they’re depicting wear white jean cloth pants, which were made and worn by the prisoners at Huntsville State Prison in the mid-1860s and then dyed with ground pecan shells or coffee grounds to get a shade of tan? Then, dadgummit, that’s what they’re wearing, right down to the correct number of stitches on the buttonholes.

Go ahead. Count ’em.

• • •

Re-enactments aren’t just shooting and dying. There are many sides of the Civil War that don’t get much play in history books and documentaries.

Trooper Jackie “Jack” Cook, 25, a chemist from Magnolia, portrays a woman who eats, sleeps, lives and fights among the men without giving a hint of her true identity. After getting tired of the politics of competitive horse riding as a teen, she yearned for an outlet to keep riding. Then a cavalry unit sent out a call for re-enactors. At 14, she was in.

Her hair short and face free of makeup, she wears up to five layers of restrictive clothes to hide her figure. Sometimes in a re-enactment she’ll be wounded and the surgeon will discover her secret, and she’ll be summarily court-martialed. And there are other tales, ones that cause her green eyes to light up as she tells about what she learned from the book, They Fought Like Demons (LSU Press, 2003).

“Just because you didn’t read it in your history book doesn’t mean it didn’t happen,” says Cook.

When the 12th Texas Dismounted Cavalry portrays its Union alter ego, the Kansas Redlegs, it becomes a guerrilla unit of members who wore red leather spats and took great pleasure in raiding pro-slavery areas in Missouri. “Everything that actually happened then we have simulated,” says Lt. Michael Fields, “with the exception of burning down a town.”

Occasionally the 36th will re-enact a scene in which a surgeon will amputate a wounded soldier’s foot and toss it—or, more accurately, the man’s real prosthetic—to the side. Another re-enactor is known to carry a realistic-looking fake arm, and when an artillery round lands nearby, he pinwheels it toward the crowd. Then he’ll stagger toward the arm, pick it up and go off dazed, looking for the surgeon.

Save for those few video-game worthy moments, though, Civil War action is slow-paced and methodical, with lines of troops marching across open fields and firing volleys.

On this day, no more than a dozen combatants get “shot.”

“Studies show that in the Civil War it took about 300 pounds of lead and 400 pounds of powder for every 10 casualties,” says Russell Birkner, a history major at the University of Texas at Arlington who’s first sergeant for the 36th. “So there aren’t a lot of casualties. Still, no one wants to be one. At national events, a lot of re-enactors drive 900 miles and it’s not fun to take a hit in the first volley and be dead for the next 90 minutes.”

Particularly when it’s hot and sunny. “You’ll be surprised how many die conveniently in the shade,” he says. “We’ll joke, ‘That shade is deadly.’ ”

How do you know when your number is up? Sometimes line officers will shout, “All soldiers with birthdays in May die on the next crisp volley.” Or, as the 36th sometimes does, the officers will slip powder charges wrapped in red instead of white paper into the men’s bags. When the soldiers draw one in battle, they die—grudgingly, because these are folks who fight to live and live to fight.

If they’re lucky, they’ll experience the moment that all re-enactors crave, when fantasy and reality become one. Veterans call it “seeing the white elephant.”

“It’s when you get so absorbed in the event you feel like you’re really back in 1863,” Cohen says. “It’s like when an athlete’s in a zone. It doesn’t last long, but it’s there. It’s like a modern time machine.”

• • •

It’s late in the afternoon. The spectators are gone; the sun is setting. The time machine has returned the soldiers to 2013, at least physically if not spiritually. They put up their weapons, maybe splash some water on their faces and prepare for dinner.

In an hour, they’ll gather in the open area between the lines of tents for a dance. A band, complete with fiddles, bones, mandolin, banjo and guitars, will play Civil War songs, and the women, clad in their period-specific finery, will dance with their partners.

Cook is excited. She gets to wash off the grime of a soldier and became a gentile Southern belle.

“It’s the best of both worlds,” she says, echoing a now familiar theme.

——————–

Mark Wangrin is an Austin writer.

See more work by Houston photographer Robert Seale at robertseale.com.