These days, one hears more about obesity than hunger. But almost 3 million Texans visited a soup kitchen or food pantry to feed themselves in 2009. Indeed, between July 2008 and July 2009, Texas had the highest rate of children—one in five—at risk of hunger among all 50 states.

The statistics are appalling, but many organizations and individuals—including electric cooperatives—are seriously working on short-term and long-term solutions to the hunger problem.

The problem is well documented by the census and by an exhaustive survey in 2009 by Feeding America, formerly known as America’s Second Harvest. This does not mean the children went without food but rather that their families lived—at least for a time—with uncertainty over whether there would be enough food in the home. A 10-year-old named Benny describes the dilemma in terms that everyone can understand: “It’s bad when kids lose energy. They might not have enough energy to think in school.” He says sometimes he has to wait a long time to eat, and it makes his head hurt: “It’s important for kids to get enough food so they can be strong and healthy.”

In statistics released in July by Feeding America, the nation’s largest hunger-relief organization, Arkansas, Texas and Arizona, respectively, lead the nation with the highest rates of food insecurity—meaning those who don’t receive three healthy meals a day—for children younger than 18.

In Texas, people who go to food banks tend to earn less than the poverty level. More than half of those surveyed said they have had to choose between paying for food and paying for utilities. More than 40 percent counted their money at the end of some months and didn’t have enough for food and rent.

Although a network of nonprofit organizations, businesses and government programs are working to combat this quiet crisis, “It’s a growing problem,” says JC Dwyer, state policy director for the Texas Food Bank Network. And volunteers have a major role to play in making sure everyone gets fed. The Hunger in America 2010 Texas State Report indicated that about 26 percent of Texas food pantries turned away qualified candidates for lack of food resources.

Almost 20 percent of food pantries indicated that they sometimes or always have to stretch their food resources by reducing meal portions or the quantity of food in food boxes.

One family’s story

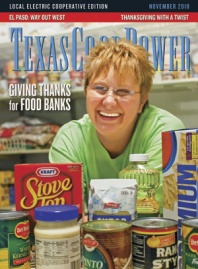

Michelle Gutierrez is one of approximately 100 people filing into a fellowship room at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in Kyle, south of Austin, waiting for their number to be called.

All are here to pick up groceries funneled through the Capital Area Food Bank of Texas in Austin. Its giant food warehouse distributes food to smaller food pantries and provides emergency food needs at 350 partner agencies in 21 counties in Central Texas.

This is the first visit for Gutierrez, a wispy blonde with a husband and three children. They can usually get by on what her husband, Javier, earns from his construction job, but work has dried up, and the kids got sick. The eldest, Evita, had to be treated in the hospital for breathing difficulties. “It’s all OK until it all goes wrong,” Michelle explains of their precarious finances.

So it is for most of the people throughout the state who, like Michelle, are grateful to pick up what this and other food banks have to offer when times are temporarily tough. Today, the warehouse has sent bread, pineapple and other fruits and vegetables, breakfast sausage, cakes and canned goods.

Among the 100 or so who have come for food are young people and old. Thelma O. Johnson, who has fluffy white hair and a smooth complexion belying her advanced age, offers a point that is important to her. “God bless food banks for old people. People that have money in the bank and food in their pantry don’t know what a blessing this is,” she said.

Where there’s help

Many Texas electric cooperatives and their members provide contributions and volunteer at food banks and pantries. Many have Operation Round Up programs that “round up” a member’s power bill to the nearest dollar, with that amount donated to local charities.

Mid-South Synergy, based in Navasota, is one of those that participates in Operation Round Up. Among its beneficiaries is the Brazos Valley Food Bank, which supplies food to over 40 hunger-relief organizations in six counties. Food bank offerings include a backpack program in which schoolchildren at risk of hunger over the weekend receive food items. The food bank also provides Meals on Wheels with 300 Senior Bags each week for volunteers to distribute.

And then there’s KBTX-TV3’s Food For Families Food Drive before Christmas every year. Mid-South Synergy oversees two drop-offs for the food drive, one in Navasota and one in Madisonville. In December 2009, the electric co-op collected 23,900 pounds of food and $9,025 in contributions.

There are too many co-op efforts to highlight, but from the western side of the state here’s another example: Big Country Electric Cooperative, based in Roby, collects nonperishable food items at each of its offices each fall. “We donate to local food pantries and charitable organizations for distribution,” said Sarah Dickson, the co-op’s member service representative. “Also, many of our co-op employees are members of the Roby Lions Club. We meet each Thursday, and our ‘admission’ to the meeting is to bring at least one canned food item for donation to the Fisher County Food Pantry.”

Food banks play huge role

Feeding America is a national umbrella organization comprising about 80 percent of all food banks in the United States. Feeding America supports the emergency food system by obtaining food from national organizations, such as major food companies (see accompanying story below on the role of Texas grocery stores), and providing technical assistance and other services to the food banks and food rescue organizations.

Nineteen food banks—warehouse-size operations—based in major Texas cities account for 83 percent of the food distributed by pantries. Food banks collect, store, repackage and distribute food to the smaller pantries. The pantries can be found in towns of all sizes. Some provide only staples, and others are equipped to handle refrigerated meat and produce. In Texas, according to the latest statistics, 72.6 percent of food pantries are run by faith-based groups, 18.5 percent by other private nonprofit groups, 4.3 percent by various levels of government and 4.5 percent by other entities.

A family in need may qualify for a government nutrition program such as SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as the Food Stamps Program). There are also government-sponsored nutrition programs for women, infants and children, public school students and senior citizens. The 2009 Feeding America survey found that only 36.5 percent of food-pantry clients received food via government mass distribution. However, many of these clients did receive commodities through local pantries.

Big cities have an advantage

The availability of fresh foods and the frequency of distribution may well depend on one’s proximity to a major food bank. In Austin, for example, anyone is welcome to pick up a box of produce and staples at any mobile food pantry stop. The trucks normally visit designated sites twice monthly. “Anything helps,” says Elena Sanchez, who received a box of groceries that included frozen pizza, carrots, potatoes and canned goods for the four people she feeds at her house.

In Madison County, there are only two free emergency food pantries: the monthly mobile food pantry at the Madison County Fairgrounds run by the Bryan-based Brazos Valley Food Bank; and the Son-Shine Outreach Center in Madisonville, a food pantry operated by about a dozen churches.

If a board of directors-approved change goes into effect this year, those in need would be able to receive food once a month instead of twice yearly from the outreach center, and individuals would no longer need a voucher from a church to receive food.

To finance wholesale food purchases and other supplies, the center runs a thriving thrift shop. Even with the thrift shop revenue, the assistance center has money to help only about 75 people per month. Coordinator Debi Raines, the wife of a rancher, says she wishes the center could do more: “The need has increased because of the economy. So many people are out of work in Leon and Madison counties.”

Growing and giving

In her home’s generous yard near downtown Kyle, Michelle Gutierrez tries to catch some time each morning to work in her ambitious garden as Evita, 5, waits exuberantly for the school bus to pick her up, Westin, 3, sprawls on the trampoline, and 1-year-old Brianna eats a handful of Cheerios in the shade of a backyard tree. Michelle’s corn, beans, squash, okra and other produce are thriving, thanks to generous spring rains.

She worries, however, that she will not be able to sustain the garden over the summer as drier months increase her water bills. Meanwhile, she harbors a hope: “My dream is getting my garden to produce enough to be able to donate to the food bank.”

——————–

Kaye Northcott is editor emeritus of Texas Co-op Power.