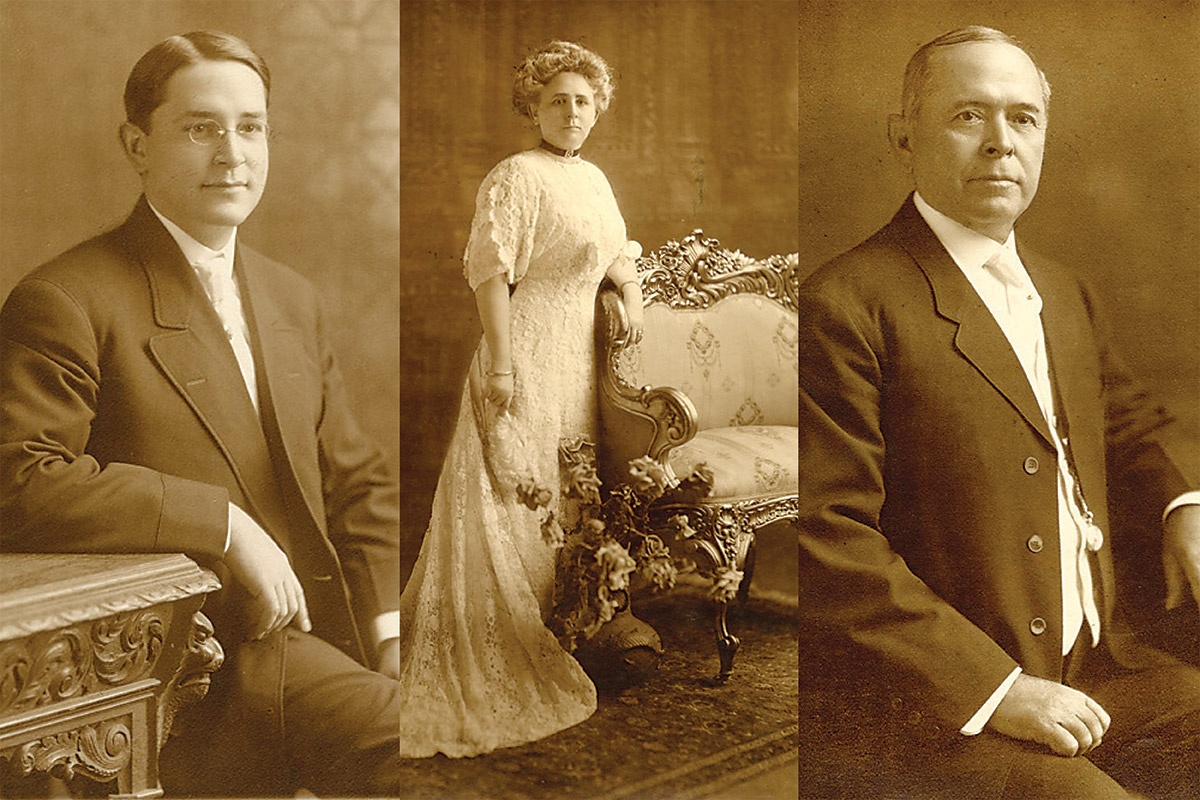

The story of the Stark and Lutcher families in Orange mirrors the rise of the East Texas economy after the Civil War. During the last quarter of the 19th century, grain milling, ranching and cotton were the region’s top producers. The timberlands remained relatively untouched, and because forests were considered an impediment to arable farmland, timber acreage could be bought cheap.

Henry J. Lutcher, a lumberman from Pennsylvania, visited East Texas with his business partner in 1876 and moved to Orange, on the Sabine River, the following year. He purchased 500,000 acres of timberland across the Sabine in southwest Louisiana and built a state-of-the-art sawmill.

The expansion of railroads in Texas helped fill demand for lumber products ranging from barrel staves to wood siding, and Texas lumbering experienced a boom that continued until the Great Depression. Through this 50-year industry expansion, the Lutcher and Moore Lumber Company became a leader in the quantity and quality of finished lumber products in the state.

William Henry Stark, a native Texan working in the mill, married Lutcher’s daughter, Miriam, and moved into management of the family business. That union of families would transform the Orange community over the next several decades.

In 21st-century Orange, the legacy of W.H. and Miriam Lutcher Stark, along with that of their son, H.J. Lutcher Stark, who went by Lutcher throughout his life, continues through venues managed by the Stark Foundation: the W.H. Stark House, the Stark Museum of Art and the Shangri La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center.

“The Lutcher-Stark Family would have been some of the wealthiest in the state before the oil boom and still among the richest even after it,” explains Joshua Cole, W.H. Stark House interpretation and programming manager.

W.H. Stark House

The W.H. Stark House, a 14,000-square-foot, 15-room Queen Anne revival mansion, is a Texas Historic Landmark and appears on the National Register of Historic Places. Completed in 1894 and inhabited by the family until 1936, the house was an architectural and cultural anchor for the nascent community of Orange and remains one of the few area mansions fully restored and open to the public.

“When this house was built, [there were] dirt streets and cowboys shooting guns in the air,” says Cole. “This house, paving the streets, bringing electricity, the churches—all this is about domesticating what was a frontier border lumber boomtown.”

The library of the Stark House.

Julia Robinson

The Stark home was not the largest in Orange or even the largest on Green Avenue when it was built. What set the house apart was its exquisite wood finishes. As the only surviving house of its size, it now dominates the neighborhood, with pitched gables and dormers, detailed woodwork, and wraparound porches.

The exterior walls combine two layers of diagonal cypress, Cole points out. “Whichever way the wind blows, this house gets tighter in a storm,” he says. In the foyer, cypress and longleaf pine exude a warm glow, and pine panels, intricate moldings and detailed lathe work line most surfaces of the house.

The Stark House’s dining room is set for a formal evening with one of the many sets of dinnerware the Stark family used.

Julia Robinson

“This home was not only gorgeous; it was completely modern with all the latest modern conveniences,” Cole says. “It was fully electrified, with indoor plumbing, making it one of the very first homes in the world to have those core technologies.”

At its peak in the early 20th century, the house was staffed by 15 full-time employees, including a cook, butler, maid, nurse, chauffeur, laundress and gardener, some of whom lived on the grounds in the carriage house and servants’ quarters.

Visitors can tour three levels of beautifully preserved rooms lined with yellow silk wallpaper, original family furniture and rugs, original ceiling murals painted on canvas, formal porcelain dining sets and Brilliant Period cut glass.

Stark Museum of Art

One block away from the Stark House waits the modern architectural contrast of the two-story Stark Museum of Art. Opened in 1978, the white marble building, with its 60,000 square feet of exhibition, storage and museum facility space, was designed to withstand hurricane winds of 200 mph.

The Stark Museum houses 9,000 pieces from the 19th- and 20th- century American West.

Julia Robinson

The 9,000-piece museum collection emphasizes art of the American West, much of it collected by Lutcher Stark. Iconic sculptures by Frederic Remington and Hermon Atkins MacNeil dominate the entry atrium. Remington’s work is of a bucking bronco, and MacNeil’s bronze depicts a Native American child learning from an elder. Porcelain sculptures of American birds by Dorothy Doughty line the atrium’s walls, and weavings by Navajo women working in the post-reservation period hang from the balcony.

“The theme is exploring America’s frontiers through the early 19th-century artists who traveled into the West primarily to record and document what was then unknown,” says museum curator Sarah Boehme.

A John James Audubon painting of mockingbirds from his personal copy of Birds of America, a signature piece at the Stark Museum of Art.

Courtesy Stark Museum of Art

One of the museum’s signature pieces is John James Audubon’s personal copy of Birds of America in enormous double elephant folio, one of only 100 remaining in the world. “Audubon set out to record and document every species of American bird, to show them life-size and in their natural habitat,” Boehme explains. “To disseminate this information, he had to make 435 prints and produce them as a book.” The volume, set under glass, is 39.5 inches tall and 28.5 inches wide, and the book is opened to a bird that complements concurrent exhibitions.

Ron Tyler, retired director of Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art, explains that the Stark’s Audubon collection is important not only because it includes Audubon’s own portfolio but also because of the naturalist’s letters, documents, sketches and paintings.

Tyler also cites the Stark’s John Mix Stanley painting of the treaty scene between the Republic of Texas and Native Americans at Tehuacana Creek near Waco in 1843.

In a nearby, specially lit hall, crystal bowls by the Steuben glass company glitter as if illuminated from within. They comprise the world’s only complete collection of the United States in crystal, which includes a specific motif for each of the 50 states and one more for the United States.

In another gallery, the work of Native American artists shifts the perspective on the West from outsider to insider. Clothing, baskets, pottery, carvings and weavings by Navajo, Pueblo and Hopi artists interpret daily life and traditions.

Katrina Nelson Thomas, director of the four Stark Art and History Venues in Orange, explains the Stark Museum’s educational mission. “When students come, they see the work in the galleries, and then they make art inspired by something they see, so they always leave with a piece they made,” she says. “We’re trying to make that connection between the collection and the art that’s made.”

The boardwalk above the cypress-tupelo swamp at Shangri La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center.

Julia Robinson

Less than 2 miles from the museum, visitors can walk through Shangri La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center, named for the fictional Tibetan paradise described in the 1933 novel Lost Horizon. Shangri La is where Lutcher Stark cultivated azaleas and camellias in abundance and created a lake where he launched a houseboat for weekend escapes in the 1950s.

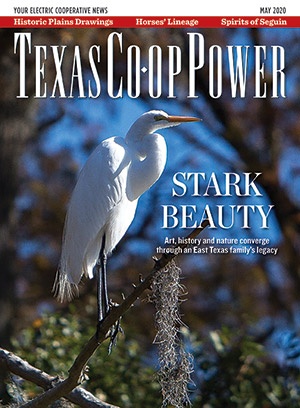

A cold winter devastated Shangri La’s plants in 1958, and the gardens closed to the public. The land reverted to a wild state, but in 2008, the Stark Foundation reopened the restored gardens to the public. Shangri La now occupies 252 acres of gardens and wetlands, with an eco-boat tour and an egret rookery that includes a viewing blind where 50,000 visitors a year watch great egrets nest and raise their young.

“What Mr. Stark did was paint a picture with plants,” says Jennifer Buckner, Shangri La’s director of horticulture. “We honor that and our connection to the museum with garden ‘rooms.’ ” Each section combines plantings that demonstrate an artistic character of line, shape, texture, contrast and color. In the shape garden, rows of dwarf yaupon form perfectly rounded bushes. The contrasts garden showcases flowers and leaves exhibiting colors from opposite sides of the color wheel.

Bowring’s cattleya orchids

Julia Robinson

The gardens revived Lutcher Stark’s original obsession with camellias and azaleas. Each spring, the flowers bloom along the shore of Pond of the Blue Moon. Miriam Lutcher Stark’s original epiphyte house overflows with orchids, bromeliads, ferns and lichens. Other areas include an edibles garden, a daylily collection and hanging gardens.

The majority of Shangri La’s property lies along Adams Bayou and is most accessible via the boat tour. Elevated wooden walkways take visitors past the Nature Discovery Center toward the dock, which is surrounded by cattails, Texas saw hibiscus, rushes and lily pads as well as bald and pond cypress. “We even have some wild orchids that grow here,” says Buckner, who always keeps an eye out for unique flora.

The property along the bayou preserves an untouched section of cypress-tupelo swamp, used as an outdoor classroom for local students. Kathleen Nelligan, an environmental educator, narrates a tour as the boat swings out onto the bayou. As guests motor quietly upriver, they catch sight of turtles sunning on logs or egrets and kingfishers taking flight above the water.

In one classroom, children learn about the swamp ecosystem firsthand. The classroom’s A-frame structure rises out of the marsh like a church, and rows of benches complete the look of a sanctuary.

“I really love teaching outside,” says Nelligan. “The kids get out here and think, yay, we’re out of school. But we are a school; we’re just a school without walls.”

Not far from the dock stands the Survivor Tree, a 1,200-year-old pond cypress that rises from the water near the edge of Shangri La. The species is not typically found in this area, but this tree was here long before Texas was a shape on the map.

“The story of the Lutcher-Starks is the story of the creation of the city of Orange,” Cole explains. To convince his young wife to remain in Texas, W.H. Stark built an elaborate house to make her as comfortable as possible. “This area was always a borderland between empires, between countries, and was very lawless and underdeveloped.”

Stark used the family wealth to pave streets, build churches and schools, and bring refinement to the burgeoning East Texas town.

See more of Julia Robinson’s work at juliarobinsonphoto.com.