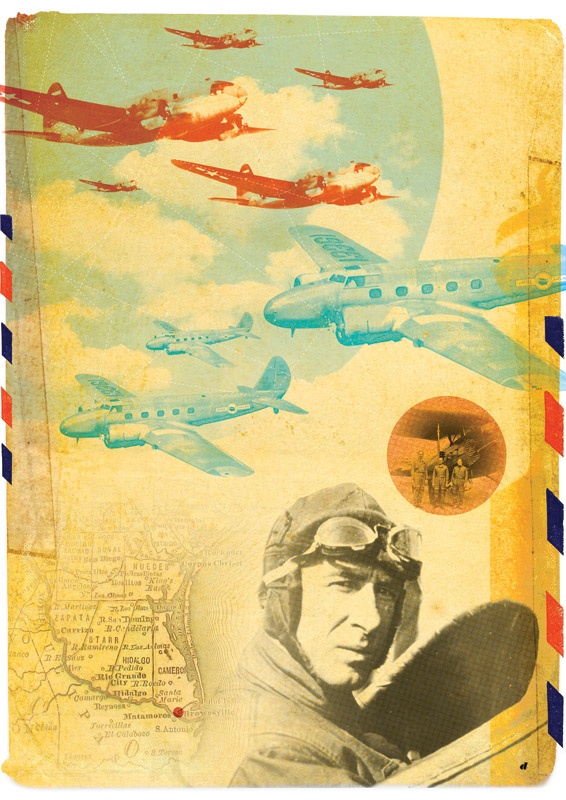

In the early days of aviation, pilots flew only when skies were clear. Flyers needed at least a view of the horizon, if not the earth below, or they became disoriented and could not tell if the aircraft was ascending, descending, flying level or turning.

Even in the best conditions, this intuitive flying demanded bold confidence. According to a U.S. Air Force manual, the pioneer pilot would “judge air velocity by the force of wind in his face and the sound of the wind in the aircraft rigging.” The earliest flying instruments gave only primitive indications of direction and altitude.

“I think those early pilots were proud of their seat-of-the-pants flying and wanted to stick to what they already knew,” says Buddy Ude, a recently retired flight instructor in Brownsville.

As aviation evolved and more Americans realized its potential for travel and mail, it became clear that weather could no longer stand in the way. A new breed of “blind” pilots soon allowed commercial aviation to really take off—and many got their start in South Texas.

By 1929, Charles Lindbergh, then Pan American Airways’ technical adviser, established the first airmail service between Brownsville and Mexico City, an 11-hour round trip.

Meanwhile U.S. Army pilots William Ocker and Carl Crane demonstrated the basics of instrument flight, then called “needle-ball-airspeed blind flying.” To fly safely in cloudy conditions, an instrument pilot had to keep a needle centered on a specific track on a ball attached to the instrument panel. If the needle was correctly aligned, then the pilot knew the craft was flying straight and level. Ocker and Crane’s research and tests appeared in the world’s first instrument flight manual, Blind Flight in Theory and Practice, published in 1932.

Following Lindbergh’s successful flight from Mexico City, Pan Am made the Brownsville airport the hub of its Latin American operations by mid-1929. With the new instrument technology, the airline established the Pan American Airways Blind Flying School. The school today is commemorated by a historical marker in front of the Brownsville South Padre Island International Airport.

David Vogin

With the airline’s fleet of Ford and Fokker tri-motor aircraft at risk and lucrative airmail contracts on the line, Pan Am’s chief engineer, Andre Priester, asked D.C. Richardson and Edward Snyder to operate the instrument flying school for the airline’s pilots. The men transformed the Brownsville airport, with its white Mediterranean-style terminal and two runways of gravel, sand and salt, into the foremost site for training commercial pilots in instrument flying.

Snyder developed an innovative instrument introduction for pilots. First he spun blindfolded trainees on a revolving chair, so they would realize that their innate “seat-of-the-pants” orientation was useless without visual cues. The next disorienting step was to isolate the subject in a box with a turn and bank indicator mounted on a swivel. This confusing experience aimed to convince pioneer pilots of their need for instruments.

Between 1929 and 1955, Brownsville’s blind flying school drilled hundreds of pilots to ignore the input from their eyes and sensations from their inner ears, forcing them to understand the imperative of trusting their instruments. Blindfolds and spinning chairs disappeared by 1951, but the pilots still learned that they could rely on flight instruments to tell them if they were flying level, in the right direction, and at an established speed in good and bad weather.

Instrument flying allowed commercial aviation to really take off, but popular culture exerted influence as well. In the 1930s pilots were marketed as American role models and heroes. Youngsters read novels with titles such as Flying the U.S. Mail to South America and The Mail Pilot of the Caribbean. Author Lewis E. Theiss wrote 12 such books with the support of Pan Am.

In practice, instrument flying not only made flight safer but also dramatically expanded domestic and international air travel for passengers and shipping. With more accurate instruments such as artificial horizons, altimeters, rate of climb indicators and directional gyroscopes, blind flying became more precise and reliable.

“The pioneers of instrument flight were up for a challenge,” says Bob Carter, who is based in the Rio Grande Valley and has been an instrument-rated pilot for 20 years. “Flying blind was cutting edge. Learning to trust their instruments, not their senses, showed how much they wanted to fly.”

Eileen Mattei is a member of Magic Valley Electric Cooperative and serves on the Cameron County Historical Commission.