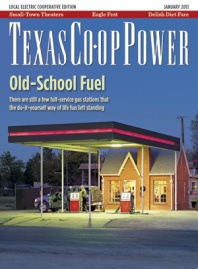

As it has for the last 83 years, the sun rises slowly over the tan brick building with the distinctive high-pitched gable roof on the corner of Doak and Seventh streets in O’Donnell, a gritty farming community 45 miles south of Lubbock. The 74-year-old man in the red T-shirt, stingy-brim fedora and suspenders unlocks the front door, turns on the lights and the gasoline pumps, opens the service bay doors and makes coffee, much as he’s done for 45 years. Then he waits for what the day holds.

Maurice Jackson already knows most of it. At 6:30 a.m., Ben Franklin, a director for Lyntegar Electric Cooperative in Tahoka, will come in, go to the back room, fill his travel cup with coffee, chitchat for a minute or two and drive his daughter to school in Lubbock.

Five minutes later, Don Forbes will stop by, read the local paper, chitchat, buy some gas and head out. He’ll be back later, with his father, to get more coffee and chat some more. And so it will go almost every day at O’Donnell Oil & Butane, where full service still reigns and old ways die hard.

O’Donnell O&B is old-school even for old-school. From the emphasis on full service to the unaffected 1920s building with the distinctive Phillips Petroleum Tudor revival architecture of the period to the steadfast Jackson, who works 12-hour days dispensing gas and good cheer, this service station is a high-octane fill ’er up of the way things used to be.

There are no giveaways of furry tiger tails or replica tanker trucks or presidential coins or sports tumblers; nor are there armies of white-suited men in bowties and caps swarming your car to check every level and pressure and squeegee your windows. Some sacrifices must be made in the interest of survival.

According to 2007 figures from the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 10,727 businesses that sold gasoline in Texas. Of those, 9,488 were linked to a convenience store.

Today, there’s one that blows the old business model out of the water.

The new Buc-ee’s in New Braunfels epitomizes the Walmartization of the gas station industry: a sprawling 18-acre, 60-pump complex in a construction-happy sector of Interstate 35 that’s expected to handle more than 5,000 cars daily. Fronted by its mascot, Buc-ee Beaver, the facility boasts 83 spotless urinals and toilets and a 68,000-square-foot convenience store—about the size of a typical grocery store—that sells everything from the convenience store staples of beef jerky and oversized drinks to Beaver Nuggets (caramel and butter-glazed corn puffs), deer feeders, an abundance of Texas kitsch—and the not-so-ridiculous notion that it’s a tourist destination, not a way station.

“They’re the new Stuckey’s,” says historian Dwayne Jones, recalling the ubiquitous gas-filling, pecan-log-boasting highway oases whose heyday came in the 1960s and ’70s. “They’re trying to create a new image of gas stations. Texans love the cowboy, larger-than-life image of the state. The attitude is ‘Stop in and see what crazy things are in Buc-ee’s.’ ”

Over in O’Donnell, they don’t stock crazy. They just pump gas, check the oil and radiator levels and tire air pressure, clean the windows—the basics.

The amiable Jackson has given his heart and soul and the last knuckle of the middle finger on his right hand—at 15, a stark lesson in how not to adjust a fan belt—to the quaint notion of putting customer service first.

Jackson got his first job as a gas jockey after dropping out of school during his freshman year at O’Donnell High School, partnered in O’Donnell O&B in 1968 and bought it outright four years later—just in time for the game-changing Arab oil embargo of 1973.

“Starting out, that was the way to do it,” he says with a shrug. “In the ’70s, they started doing away with the smaller stations. But a lot of older people like to be waited on, like to have their windows washed, their oil and water checked and their gas pumped.”

And Jackson is nothing if not a creature of habit. Aside from Sunday, when he closes for the Sabbath—and that fishing trip he took with clients in ’74—he can be found at the station from 6 a.m. to 6:30 p.m.

“We always did it, so we’re used to it,” says Jackson, whose wife, Patsy, has been his bookkeeper for 40 of their 55 married years. “It’s for the people. I very seldom close, because of the people. That’s my business. I have some customers I’ve had since 1968.”

It’s unclear how many full-service-only operations like Jackson’s are still in business, but the number is low and dwindling. And with each closing goes another slice of Texana.

With thousands of miles of roads, and an adventurous spirit to boot, Texas has long been the perfect breeding ground for a love of the road. Trouble was, the roads didn’t always love back, many of them unpaved, dirty and with limited access to gasoline. Making the experience more appealing became a growth industry.

Jones, the Galveston Historical Foundation’s executive director, has researched the role of the service station in Texas history, assembling “A Field Guide to Gas Stations in Texas,” a 148-page report for the Texas Department of Transportation on the architectural history of service stations in Texas, primarily to help road planners recognize a historically valuable former service station when they see it.

“It was all service-oriented,” Jones says of the resulting outgrowth of service stations. “It was a way to make everyone enjoy the experience. Because of the time, because of the cost, it became a luxury that could be afforded.”

In 1947, Frank Ulrich, a California entrepreneur, opened three “gas-a-terias” in Los Angeles, where patrons were allowed to dispense their own gas. Despite industry objections, the practice gained a toehold but didn’t take off until the early 1970s, when environmental awareness and economic recession were compounded by the OPEC oil embargo.

“The oil embargo suddenly made people think of oil and gas as a priced commodity, not available to everyone,” Jones says. “Geopolitics, working with environmental concerns that there were limits to the resources, made self-service the way to go.”

Full-service stations were unable to obtain their allotment of gas, and profits were gutted, forcing cost cutting—and the workers were the first to go. Struggling for survival, the industry began moving toward self-service, and baby boomers, reveling in the technological advances fostered by World War II and NASA’s race into space, were keen to handle the technology, even if it was only at the local pump.

(Only Oregon and New Jersey still bar the practice, clinging to the fear of rampant self-immolation.)

Self-service has become so prevalent—the number of full-service stations nationwide had shrunk from 220,000 in the 1970s to 40,000 in 1997—that Jackson sometimes has to explain the process to confused drivers.

“Some people have never had full service,” he says. “They expect to wait on themselves.”

Jackson recalls a car of young girls terrified that he was going to hijack their car when he started opening the hood. Ironically, they were the grandchildren of the woman who sold him the station.

It’s midday. Jackson plans to keep seeing the sun rise and set from that little brick building at Doak and Seventh for as long as he can. His grandson, Courtney Stewart, is in line to take over the station when Jackson moves on. He says he’ll keep the tradition going. “I collect antiques, and we like to eat at home,” says Stewart, 29. “I like the older style of living.”

From a bottom-line perspective, it helps that the bulk of O’Donnell O&B’s income comes from diesel sales to area farmers, though cotton farmers have been hit hard by the drought. With the trend away from fossil fuels and toward alternative energy and the economic influences that favor the new and different, the future of full-service stations like Jackson’s is uncertain. Then there’s Jackson, and his two artificial knees, the missing back discs, the cataract surgery, the shoulder reconstructions, the spinal tap, the sciatica and the neuropathy. But the man is game to see many more sunrises. “Just keep on trucking,” he says. “I’ll be here as long as I can.”

More than 300 miles and a world away, another man fills his own tank at a gigantic convenience store and heads inside to mull which of the more than 30 varieties of beef jerky he’ll buy. Out front, a cartoonish 4-foot bronze beaver is smiling, waiting on the next eager customer to pose for a snapshot. His sun is rising, for the time being.

——————–

Mark Wangrin is an Austin writer.