Tales of Texas oil booms can be stranger than fiction, and none more so than the colossal East Texas oil field of Rusk, Gregg, Upshur, Smith and Cherokee counties. The 140,000-acre field was the world’s largest when Dad Joiner and Doc Lloyd discovered it in 1930. One oil historian declared the behemoth of bubblin’ crude the “Granddaddy of Them All.”

Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner, a 70-year-old, Shakespeare-quoting wildcatter, and A.D. “Doc” Lloyd, a self-taught geologist and former medicine show operator, might seem an unlikely pair for such a discovery.

Joiner had dreamed he would find an ocean of oil in the rolling hills of East Texas, and he found the landscape that matched his dream on Daisy Bradford’s farm south of Kilgore. To raise drilling funds, Lloyd produced reports proclaiming that Daisy’s acres contained a spot “known in the oil business as the apex of the apex, a situation not found anywhere else.” Astonishingly, every statement Lloyd made was incorrect except for one: that Joiner would find an immense pool of oil in the Woodbine sand at 3,550 feet.

Because the underground oil ocean was sandwiched in a formation called a stratigraphic trap that was new to petroleum geologists at the time—the big oil companies had passed over this neck of the Pineywoods. But after the rig Daisy Bradford No. 3 hit black gold, the Lou Della Crim No. 1 struck a gusher further north. Then the Lathrop No. 1 came in near Longview, and suddenly it seemed, the whole world rushed to East Texas.

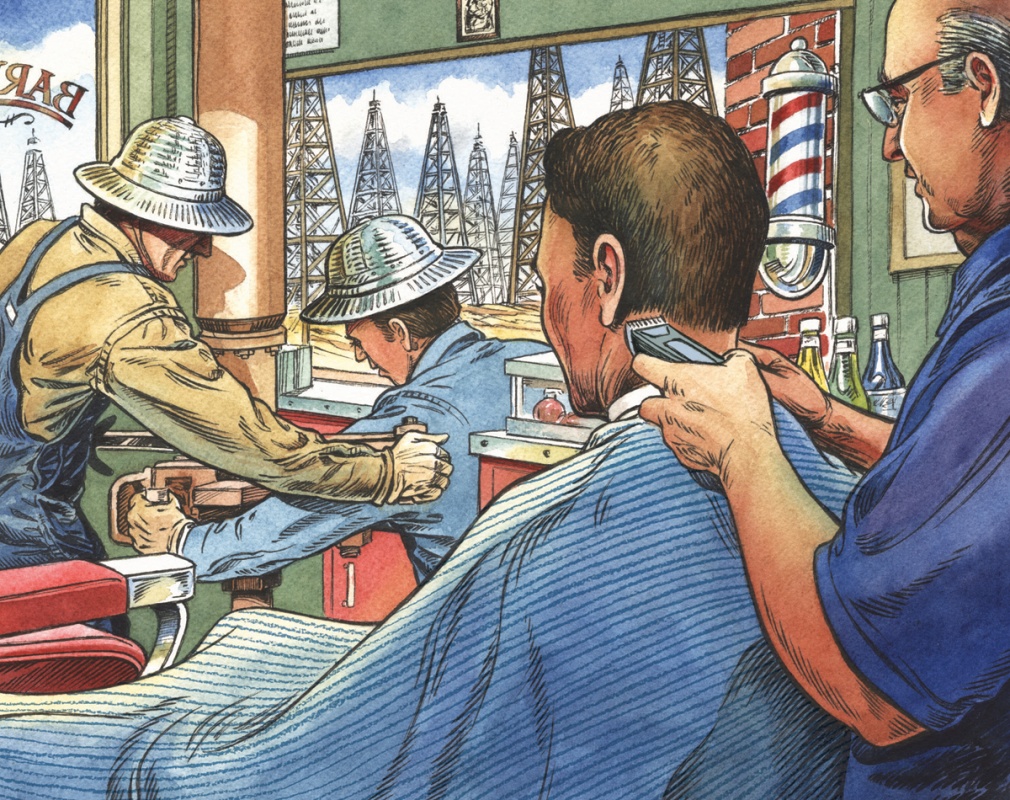

“It was the California Gold Rush, the Klondike, the Oklahoma land rush, and the wildest of past oil booms rolled into one,” according to “The Last Boom.” Kilgore became the heart of the boom as thousands of Depression-beaten job seekers arrived. Some 1,100 derricks went up in the city limits alone as wildcatters drilled in churchyards, flowerbeds and even inside a barbershop.

“In a few weeks, there were men in khaki pants standing in every square inch of town,” Kilgore resident Nanette Wickham reminisced. “People were coming in and building anything to give them shelter. Yards were full of shacks and cars.”

Investors in the discovery well learned that Joiner had oversold shares in the Daisy Bradford No. 3. Beset with lawsuits, Joiner sold most of his East Texas holdings to H.L. Hunt, who parlayed the Pineywoods gushers into his status as “The World’s Richest Man.”

The abundance of East Texas oil and the breakneck pace of extracting it played havoc with the market, driving the price per barrel to as low as a nickel. To stabilize prices, the state passed laws limiting production, which were enforced by 1,200 National Guard soldiers dispatched to the giant field.

The wisdom of conservation and limits on production became even more evident a decade later, as the country was drawn into World War II. Delivered to East Coast refineries through the Big Inch, the world’s largest pipeline at the time, East Texas crude provided the Allied forces with more fuel than was produced by all the Axis powers combined.

To date, the giant field has produced more than 5.3 billion barrels. “And there’s still hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil here, and there are wells from the 1930s still producing with the original pumpjacks and the original casing,” says Kilgore oilman and historian Terry Stembridge, who has collected thousands of vintage photographs of the East Texas field.

“Remember East Texas,” say contemporary wildcatters who know their industry’s history, when skepticism emerges about whether new wells will be dry holes or gushers. “Remember East Texas!”

——————–

When Gene Fowler’s mother was born in 1922, her family was living in a Mexia oil field tent, and her father later worked for a Kilgore oil field supply company.