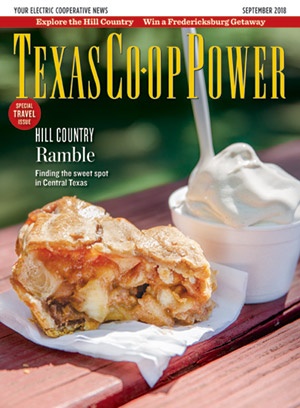

I intended to try only the apple turnover.

Five minutes later, I stand at the counter, balancing a jar of apple butter, a jar of jelly, a strudel, a slice of pie and the turnover. That’s when another visitor mentions the apple ice cream. “Why hasn’t Blue Bell caught on to that flavor?” he asks the cashier.

I turn back to find the ice cream.

Outside Love Creek Orchards’ Apple Store in Medina, I spread my bounty on a bright red picnic table and sample the pastries. I savor the pie’s flawless golden crust. The ice cream is light, not too sweet, and goes down way too easy.

Such are the pleasures you’ll find in the Texas Hill Country, which is adorned with gems like this shop. Visually, the region offers a rolling landscape of limestone-and-granite hills, clear rivers, cedar and cypress trees, and regional haunts that delight weekend visitors and seasoned travelers.

Apple turnover at Love Creek Orchards’ Apple Store in Medina.

Julia Robinson

Love Creek Orchards’ Apple Store.

Julia Robinson

More than 150 years ago, German immigrants were lured to Central Texas by tales of fertile soil and freedom from oppression. Instead, they found rocky fields that had to be cleared by hand and the threat of contentious and fast-moving Comanche. The early settlers persevered and built towns of precise and tidy stone structures, each a day’s wagon ride—about 20 miles—from its neighbor. Today, we know some of those settlements as Fredericksburg, Kerrville, New Braunfels, Medina, Mason, Llano and Camp Verde.

FM 337 between Camp Wood and Medina.

Julia Robinson

Starting in the southwest corner of the Hill Country, FM 337 between Camp Wood and Medina is one of the most scenic drives in Texas. Along a curvaceous stretch popular with motorcyclists, signs warn of “Falling Rocks” going east and “Fallen Rocks” going west, a curious temporal twist. The rise of the Edwards Plateau reveals itself along this 60-mile route, displaying limestone cliffs and following the meandering Medina River.

Along the way, I read about community history. Vanderpool grew out of a Republic of Texas land grant in 1849. Originally called Bugscuffle, the town was abandoned following Comanche raids but re-established in the 1880s. Camp Verde was established to service the region’s military outposts.

East of Medina, freethinkers, including doctors, scholars, philosophers and aristocrats who fled the German Revolution of 1848, sought to establish intellectual, secular and democratic societies advocating scientific reason and religious freedom. They built the towns of Boerne, Comfort, Luckenbach and Sisterdale. Residents met to discuss politics, philosophy and literature; in such meetings, they spoke in the intellectual’s language of Latin, so the towns were dubbed the “Latin Colonies” of Texas.

Boerne was founded in 1849 and originally named Tusculum, after the home of Roman writer and orator Cicero. In 1852, it was renamed for Jewish-German journalist and satirist Karl Ludwig Börne. The town was known as a health resort in the late 1800s because of its proximity to Cibolo Creek and the Guadalupe River.

Cave Without a Name, near Boerne.

Julia Robinson

I drive north along FM 474 to find the Cave Without a Name. Mike Burrell, tour guide and cave manager, leads me down 80 feet of staircases through layers of geologic and human history. At the first landing, a pile of bones is evidence that eons of unlucky animals fell to their deaths through the small entrance above. Down another level, we find a ledge where a whiskey still dripped rebelliously during Prohibition.

In 1935, a group of youngsters shimmied down the sinkhole entrance with a kerosene lantern and crawled through a series of tight turns before finding cathedral-like rooms.

Burrell lights up the rooms as we walk through, one side formed by the subterranean streams of the Guadalupe River, the other by the slow drip of mineral-rich water onto the cave floor. Some of the largest calcite formations in the nation can be found here, and 3½ miles of the cave have been mapped, making it the seventh-longest in Texas.

We pass a small platform where the owners host concerts. Burrell replays a few previous performances on his phone and offers me a chance to sing. I manage a few lines of the Battle Hymn of the Republic and marvel at the resonance.

Whiskey pecan and Key lime pie slices at Tootie Pie Co. in Boerne.

Julia Robinson

Back at ground level, I rush to Tootie’s. Ruby Lorraine “Tootie” Feagan moved her 20-year-old pie company from Medina to Boerne in 2005. The new building, situated in a business park, serves as a bustling outpost for Tootie Pie Co.

To reach the unlikely address, I zoom past a wrecker service and RV repair shop to find the modest storefront, where cubicle walls support a chalkboard listing a dozen offerings and seasonal specials. It’s not a homey setting, but the pies are delicious. I sample the heavenly chocolate, lemon icebox and pecan, rolling my eyes in delight.

Another day’s wagon ride up Interstate 10 takes me to Comfort, where there are more than 100 historic buildings constructed before 1910. Seven of them, including the old Inguenhuett General Store, were designed by British architect Alfred Giles.

High’s Cafe & Store drew in coffee lovers when it opened on High Street in 2005 and has become a reliable staple for chef-inspired café fare. Proprietors Denise Rabalais and Brent Ault attract a dedicated following, including a steady stream of locals who catch up and share a bite on the covered patio.

Comfort was another of the Latin Colonies, proud of independent thought and human rights for all. In 1862, eight years after the town’s founding, the Confederate Army called upon the locals to join their side in the Civil War. Thirty-six men and boys who refused were killed.

I walk a half-mile down the street from the café to see the Treue der Union, or “Loyal to the Union,” Monument. Etched into the surface of the 20-foot-tall limestone obelisk are the 36 names. The 1866 dedication ceremony was front-page news even in Harper’s Weekly.

East of Comfort, RM 473 turns onto Old Number 9 Highway and twists past fields of livestock penned by hand-stacked rock walls. Old Tunnel State Park was originally a railroad tunnel built in 1917 to link Fredericksburg to the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad. After falling into disuse in the 1940s, the area was turned into a state park; summering Mexican free-tailed bats took roost in the old tunnel.

I arrive around 7 p.m. and make my way to the viewing area just in time for the evening show. Three million bats stream out of the cave entrance in a counterclockwise wave of mammalian fluttering. “The bats circle around a few times to get elevation to get above the trees, and it looks like a tornado of bats,” says park superintendent Nyta Brown. “I never get tired of it.” Each bat eats its weight in insects each night.

Fredericksburg was first settled in 1846, the second colony founded under the direction of the Adelsverein, the Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas. Unlike the freethinkers, the settlers of Fredericksburg were religious—evangelical Protestants, Lutherans, Methodists and Catholics. Each was given a parcel of farmland and a lot in town where many built “Sunday houses” near their house of worship.

Ray Hernandez, known as Chief Broken Eagle, speaks with students at Fort Martin Scott.

Julia Robinson

Doug Baum poses with two of his camels during Fort Martin Scott Days.

Julia Robinson

Living history re-enactors at Fort Martin Scott in Fredericksburg.

Julia Robinson

Fort Martin Scott on the southeast edge of Fredericksburg was the first U.S. Army post on the Texas frontier, built in 1848. The town had negotiatied a treaty with the Comanche by 1847, and soldiers at the fort were the first line of defense.

I wander among well-preserved remnants of the fort on a “living history” weekend. The tents of re-enactors and educators line the circle track, and classes of fourth- and seventh-grade Texas history students visit the encampments of Native Americans, soldiers and other period actors.

In one corner, Ray Hernandez, aka Chief Broken Eagle of the Tonkawa tribe, has set up a teepee and shows family heirlooms to wide-eyed children. Rita Rice, the living history coordinator, appears in the officer’s quarters in 1890s period dress. She walks students and adults through the two-room structure, pointing out features of frontier living. “I love seeing the kids in awe when I describe what people lived like back then,” she says.

On the lawn just outside the fort, Doug Baum is tending his camels, Richard and Jadid. Curious groups gather to take pictures and ask why in the world there are camels in Texas.

Baum explains that in 1857, U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis directed the importation of 34 camels from Egypt to establish a camel corps based in Camp Verde. The animals quickly proved their worth by carrying twice the usual load of survey teams and mail-carrying ventures.

The Civil War interrupted and ultimately doomed the camel experiment, but Baum keeps the curious story alive with this Texas Camel Corps. “I fell in love with the camels and had to get a few of my own.” He now leads camel tours through West Texas.

I turn north on State Highway 16 toward Llano, a frontier trading center that grew to prominence in the 1880s when iron deposits, granite quarries and brick-making sparked a boom period in anticipation of the town becoming the “Pittsburgh of the West.” Today, the city still is known for granite but also embraces its connection to Highland Lakes tourism.

Llano’s Leonard Grenwelge Park, along the south side of the Llano River, honors the city’s heritage in a new and charming way. Just east of the dam and Inks Bridge, the park has become a civic art project of rock stacking.

Leonard Grenwelge Park in Llano features towers of rocks called cairns lining the shore of the Llano River.

Julia Robinson

Resident Belinda Morgan started the Llano Earth Art Fest to bring attention to Llano’s natural resources. The 2015 fest created the first World Rock Stacking Championship. The springtime festival leaves stacks of rocks, called cairns, along the riverfront, inspiring others to contribute their own stack.

An ornate sandcastle grabs my attention as I pull into the parking lot. Then an 8-foot-tall dirt armadillo with a saddle on its back emerges from the bridge abutment. I pick my way down the granite boulders toward the water as rock cairns take over the landscape. Arches of rock defy gravity and rival the steel bridge over the river. On hot days, people create their stacks along the shoreline while standing in the cool water. This weekday, I see few visitors, and the park feels like an archaeological mystery created just for me.

Before I head back to the car, I try my hand at creating a stack, collecting medium-sized stones around my feet. Daily stress melts away, and my whole world joyously focuses on the fulcrum between rocks. Delightful.

Gorman Falls at Colorado Bend State Park near Bend.

Julia Robinson

Gorman Falls at Colorado Bend State Park near Bend.

Julia Robinson

North of Llano, I turn off Highway 16 at Cherokee and follow country roads to Colorado Bend State Park for a glimpse of Gorman Falls, a treasure of the Hill Country. The day is sunny but cool, and I head straight to the trailhead. Signs remind hikers to bring water and sunscreen, even though it’s only 1.4 miles to the falls. A few minutes on the trail helps me imagine an ill-prepared summertime hike.

The trail is easy but rocky, and it takes my full attention to keep my ankles true. After more than a mile, I come to a steep vertical descent down slick rock (thank goodness for handrails) to the hidden fairy pools of the travertine falls. Verdant green mosses drip water into clear cascading basins. The temperature here is 10–15 degrees cooler than the bright, open flats above, and I bask in wafts of misty breeze coming off the face of the cliff. A few feet from the falls, the titular bend in the Colorado River provides a place to cool yourself and your dog before heading back up the trail.

Now the incline of the trail feels more pronounced. I stop to catch my breath and admire the blooming cactus and try to listen for birdcalls coming from nearby trees. As I head for the parking lot, I pass hikers on their way down, watching their steps, raising their hands against the midday sun and reaching for their water bottles. I smile the secret smile of having seen the hidden splendor, knowing it was worth the struggle.