I grew up in a simpler time. A time before central air and heat, cable TV and paved roads. I guess others had those things in the 1980s, but not me. I grew up on my family’s Texas ranch, one that’s been ours for more than 100 years, in a tiny house built in the 1920s. With two bedrooms, one bath and a kitchen that also served as the laundry room, pantry and gathering place—I guess you could say “the heart”—its footprint was just under 1,000 square feet.

It was a modest house—but a grand home.

It spoke to us through the creaking floorboards, the rumbling water heater in the kitchen and the moths fluttering against the lighted windows at night. Horseflies and dirt daubers clung to the screen doors, thirsting to be let into the room chilled by a swamp cooler. This house was not built with modern amenities. There was no foyer, formal dining room, guest bedroom or office. For that matter, there wasn’t even a door to the bedroom that my sister and I shared.

But what it lacked in luster, it made up for in love.

Each night, we’d gather around the small table in the center of the kitchen for supper, holding hands to pray over our meal before we ate. Friends who came to stay with us remarked how “cool” it was that we dined as a family. Even then, many Americans were so busy with their lives that they frequently would scarf down a sandwich while standing over the sink, or microwave a Hot Pocket while staring at the TV.

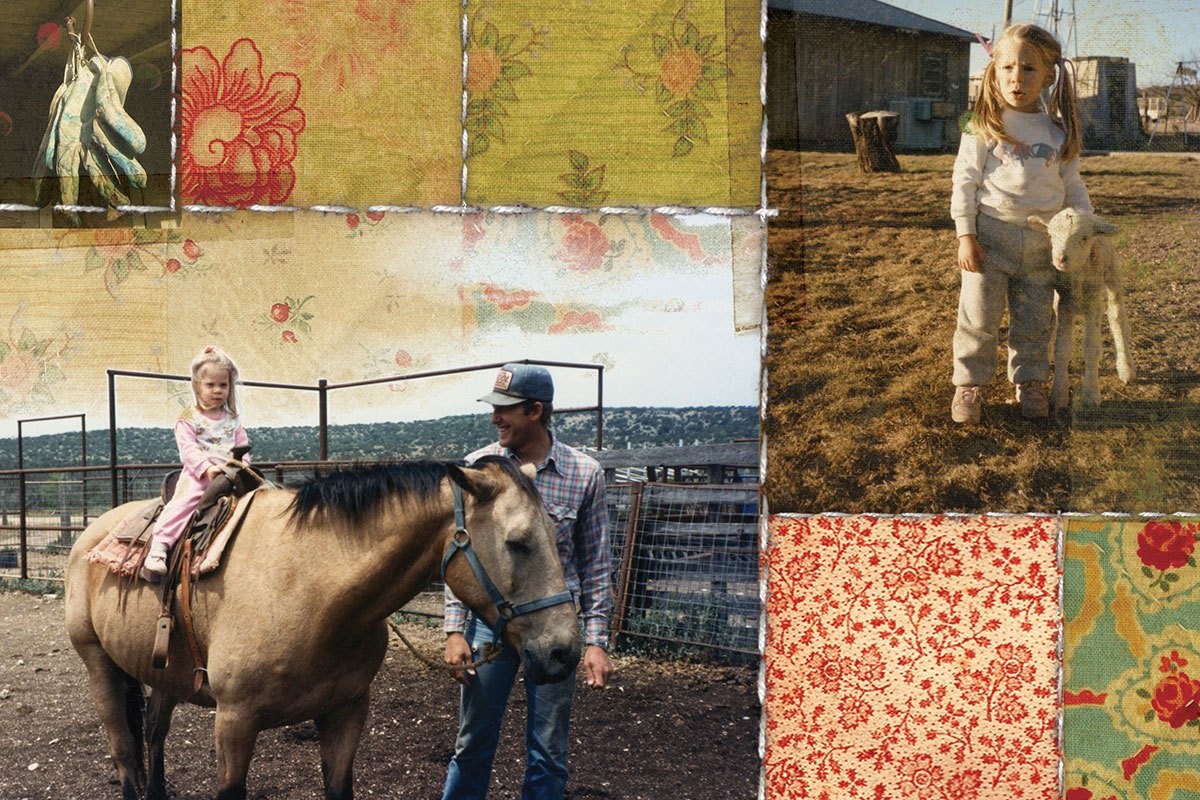

The smallness of the house gathered the four of us—my mom, dad, sister and me—quite close in a way that modern, spacious architecture often fails to do. There was no room to retreat to for privacy on the phone. The three of us girls regularly fought for the bathroom, curling our hair and brushing our teeth over each other’s shoulders. We had only one TV, with three channels, so whatever one person watched, we all watched together.

The 6-by-9-foot bathroom was wedged between the two bedrooms, with a door on either side. It was just large enough for a claw-foot tub, toilet and sink. If we wanted to take a shower, we slipped on our flip-flops and trekked 50 yards to the bunkhouse, where hunters stayed during hunting season. When we got older, my sister and I mostly chose that option, and I can remember running back to the house in the dark praying that I wouldn’t step on a rattlesnake.

Yes, rattlesnakes were aplenty out there. Country folk know these creatures well. As soon as we were old enough to walk, my sister and I got a lesson on what to do if we saw a snake—don’t touch it! We lost many kittens to the vile reptiles and watched my dad shoot several. A rattle about 4 inches long lay on the windowsill above the sink, reminding us to watch out for them every time we washed up for supper. One time in high school, my dad thought it would be funny to curl a dead one up on the porch for my “city” friend to find the first time she came out to stay the night. He was wrong.

I learned a lot from the animals that surrounded that house, like how the scissor-tailed flycatcher will tell you summer is here, or the crawling tarantula means rain is coming. They also taught me about death. Sometimes the lambs didn’t make it through the winter, or a white-tailed deer would get tangled in a fence. I can remember crying through the screen door one summer as I watched my beloved blue heeler, Sassy, fight a fox in the middle of the day. Dad said the fox must be sick, possibly with rabies, to come up to the house with the sun at the top of the sky. Sassy had to be put down; it was awful.

In those days, I took growing up on a ranch in Texas for granted. When my parents made the decision to buy the ranch from the rest of the family, I begged them to buy a house in town instead. I wanted a house like my friends had. One that was walking distance from stores, where we could have pizza delivered, with a pool in the backyard. But they told me I would be grateful someday.

Now I am.

My ancestors traveled from Sparta, Tennessee, and homesteaded the ranch in Irion County, west of San Angelo. I can’t imagine the grit they had to settle in that wide-open land. My great-great-grandfather James and his brother, Hosea, were among the very first to live on the ranch. Hosea and his nephew, Houston, James’ son, built our ranch house and lived there as bachelors in the beginning. Dad said they actually stored hay in one of the bedrooms.

It was a box-and-strip house, a popular method of construction in West Texas at the turn of the 20th century. They laid a box frame on the ground, and then 1-by-12-inch boards were nailed side by side vertically to the frame with thin, 1-by-4-inch strips nailed over the gaps. There were no 2-bys anywhere in the house. Nor was there any insulation in the 1-inch-thick walls. Single sheets of newspaper were added as insulation later in the ’40s, when the house was sheathed with plasterboard.

It takes a tough soul to survive the long winters and blistering summers in a house like that. But I wasn’t the first to do it. The first woman to live in that house was Great-Aunt Lorene, who married Houston. She was from green and lush Seattle, Washington, and she must have fallen head-over-heels in love to leave the Emerald City and move out among the mesquites and prickly pear. She lived in the house before it had electricity and was instead powered by a wind-charged battery system and lit by kerosene lamps. In the mid-1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt started the Rural Electrification Administration, which brought co-op electricity to rural farms and ranches, and I’m sure made Aunt Lorene’s life a lot easier.

My granddad described her as “prim and proper,” always donning a nice dress and gloves when she went into town. She was known as a great cook, famous for her chocolate pie and strawberry cake. She is the one who planted the two spartan juniper trees that flanked the house and the pecan trees in the yard that my sister and I played under.

Granddad planted an oak tree in front of the house and later added more around the barn. I think about how the generations before us gave to the land rather than took. They simply built what they needed, nothing more. There is now an oil lease on the land, and I watch as it is populated with wells. My mom passed away the year after I moved out of that house for college. To me, the house never was the same after that.

My dad remarried. So over the years, he found two amazing and tenacious women who loved him enough to move out to the ranch. He is one lucky man.

Our growing family created more demands than that tiny ranch house could meet. It is now gone, replaced by a larger one, fit for entertaining and big holiday gatherings, but it served its purpose while it was here.

Ironically, as I write this memoir, our air conditioner has gone out, but it’s not so bad to me. I say to my husband as we lie in bed with the fan on and the windows open, “It’s like the good old days.” The bugs and birds outside sing us to sleep.

Growing up in that old ranch house taught me many lessons. It taught me that I don’t always have to adjust the planet to fit my needs; that sometimes I need to adjust to fit the planet’s needs. It taught me how to be still, listen to the environment and be content being by myself. It taught me that granite countertops and Jacuzzi tubs, though nice, don’t make a house a home; it’s the people inside who do.

——————–

Brenda Kissko, a member of South Plains EC, has finished her first novel, a coming-of-age story set in West Texas. Visit her at brendakissko.com.