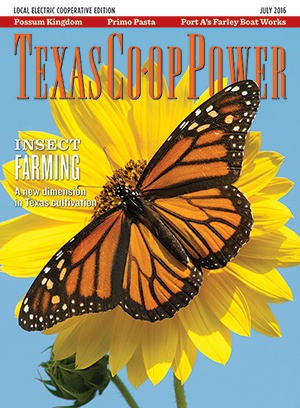

On 24 acres north of Rockport, Tracy Villareal and Barbara Dorf recently started a farm. They ship their livestock all over the state and beyond—by mail.

Big Tree Butterflies raises monarch butterfly eggs and caterpillars for schools and educational programs and adult butterflies for exhibits and releases at memorials, weddings and other events.

Across the United States, you’ll find about 100 butterfly farms, most of them small, one-person operations. Insect farmers also raise grasshoppers, mealworms and crickets for human consumption, and praying mantises and ladybugs to sell as natural pest control. People have kept bees for centuries, of course, but beekeepers operate less like farmers than landlords, providing hives and habitats in exchange for honey, pollination services or both from the bees.

Insect farming, harvesting the creatures themselves, is a relatively new practice in Texas and the United States, and it is not without some controversy. A key concern is that insects distributed commercially might spread parasites or diseases that could affect wild populations. Monarchs, for example, can carry a parasite with a tongue-twister name—Ophyrocystis elektroscirrha, or OE.

“If you bring eggs in from the wild, raise a single generation and let them go, that is probably not a problem,” says Lincoln P. Brower, research professor of biology at Sweet Briar College in Virginia. “But breeding several generations commercially, unless you are extremely careful, the incidence [of OE] builds up from one generation to the next.” Partly because of that risk, Brower and several other scientists and conservationists recently released a statement recommending against large-scale captive rearing of monarchs for release into the wild.

Villareal points out that proper practices on butterfly farms reduce risk. “Our initial stock came from a renowned Florida farm, and because we want to keep the gene pool healthy, we took some caterpillars off natural milkweed in the fall,” he says. “We carefully screened those and released them into a contained area of milkweed. Now, everything is self-contained, so we don’t collect any more in the wild.”

In Maypearl, Nikki Camp raises monarchs, painted ladies and Gulf fritillaries at 13-0 Country Butterflies. Her small operation buys eggs from larger farms and checks all new stock for disease. Screening for OE is relatively easy but must be done constantly.

No law requires this testing, but Wayne Wehling of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service says he has been impressed with the growth in best management practices during the 16 years he’s worked with butterfly farmers.

“It is amazing, the lengths people go to avoid disease issues,” he says. “Obviously, if you have disease problems, you won’t have a product to sell. The folks who do this in the mainstream do a very good job and know techniques for keeping their livestock clean and healthy. We only allow release of adult butterflies into the environment, and generally, if you have a butterfly capable of flying away, you have a healthy butterfly.”

Most butterfly farmers really care about their stock, Villareal says. “As with any kind of animal husbandry, you have people who do it very well and have high standards—and those who don’t.”

Larry Gilbert, director of the University of Texas Brackenridge Field Laboratory in Austin, says he worries about butterfly releases interfering with scientific research.

“We study the genetics and biology of wild species and assume that what we sample in nature legitimately reflects interactions between that species and its environment,” he explains. “If people bring butterflies in from wherever and let them go, [those butterflies] aren’t local and scientists can’t make assumptions about the wild population anymore.”

Butterfly releases could also affect the ability of scientists to track migrations. “You don’t know whether you caught a wild butterfly or one that was released,” Brower says. “Anything that mucks up that research is too bad, because we need to understand the natural system.”

The USDA limits releases to 250 specimens, but even limited releases could cause confusion, scientists say.

Timing also plays a role; releasing butterflies at the wrong time could mean none survive. Camp sells butterflies between late March and November—when temperatures in parts of Texas reach at least 60 degrees. She stops selling monarchs in early November, when they migrate.

“I interview potential clients to find out the purpose of a release, the atmosphere and the surroundings,” she says. “You have to think through the whole picture, what is going to happen to the butterfly after a release.”

Interstate transport of butterflies at any stage, to or from a farm, requires a permit from the USDA. The agency allows release of eight species in Texas: Gulf fritillary, eastern monarch, zebra longwing, giant swallowtail, eastern black swallowtail, red admiral, painted lady and American painted lady. Monarchs cannot be transported across the Continental Divide, as research has suggested a difference in disease susceptibility between western and eastern monarchs, Wehling explains.

Even those opposed to butterfly farming recognize an upside, though: education. “School kids raising monarchs, tagging and releasing them has a huge educational value,” Brower says. “It really engages them, and the value of that versus the potential damage has to be weighed carefully. The main thing is to be as careful as you can, know what you are doing and realize there can be problems if it’s not done right.”

Other insect farmers encounter other concerns. Robert Nathan Allen, who produces crickets for human consumption, deals less with controversy than with people’s reluctance to eat insects. He points out that about 2 billion people around the world eat insects, and humans have done so for centuries.

In 2012, Allen started Little Herds, a nonprofit that encourages eating insects, and in 2014 helped Aspire Food Group found a cricket farm in Austin. It joins several dozen operations nationwide in a market where demand outpaces supply of cricket-based energy bars, pastries and chips. Fast Company says edible insects are a $20 million industry in the U.S.

Most of Aspire’s crickets are processed into flour, and one of its customers, Crickers, uses it to make crackers. The Austin company’s founders, Leah Jones and Megan McDonald, point out that crickets provide protein, including all nine essential amino acids (amino acids are the building blocks of proteins), healthy omega-3 fats, vitamins B-12 and B-6, and minerals such as calcium, magnesium, iron and zinc. Plus, Jones says, “Cricket flour is delicious, with a savory, nutty flavor that lends [itself] well to baking.”

These little herds spend their lives in a climate-controlled warehouse, hatching from eggs in one bin, then moving into ever-larger bins as they grow, eating a custom blend of corn, soy and kelp. In five or six weeks, a cricket matures and lays its own eggs, Allen says. The operation then freezes the critters and sends them to a facility that produces the flour. Some restaurants serve the crickets whole.

“The idea of responsible, organic and local food outweighs the fact that it is weird for some people,” he says, “and others try it precisely because it is weird.”

The farm grows stock specifically for human food, and because crickets and humans are so genetically different, no diseases pass between the two. There is some anecdotal evidence of allergic reactions, says Allen, but it isn’t clear what actually caused those reactions. Aspire Food Group tests for pathogens and bacteria, and handles everything according to health codes and Food and Drug Administration regulations.

Properly regulated and operated, butterfly farms can contribute to knowledge about these species and what we all can do to help keep them healthy. Cricket farmers can produce healthy food using fewer resources.

“Insects have a very small carbon footprint,” Allen says. “People all over the world already eat them, and farming them is not really a complicated process.”

Sounds like tiny livestock could become a big thing.

——————–

Regular contributor Melissa Gaskill specializes in science, nature and travel.