It’s not often that Sylvester, Texas, makes the news.

So naturally, as a Fisher County native, my curiosity was piqued when I saw the town’s name tick across the bottom of the TV screen in early March. The headline said that the remains of Frank C. Ferrel, a soldier from Sylvester, had been identified and would be returned home soon for a proper burial with military honors. My heart was filled with pride and my arms were covered in goose bumps while I continued my routine of getting ready for work.

Within a few days, a more detailed account of the story appeared in the Double Mountain Chronicle, captured in the narrative of the Fisher County Historical Commission’s March meeting highlights.

Roenna Thomas, a Sylvester native and descendant of Ferrel, and whom I know through her Big Country Electric Cooperative membership and visits to the co-op’s annual meeting and open house, had made a presentation to the commission about Ferrel.

I knew that I wanted to share Thomas’ findings—which she readily granted permission for me to do. Thomas said that she had received many phone calls from people far and wide, some of whom had a connection to Fisher County and many who did not, and she was blown away to know how many people genuinely cared about bringing Frank C. Ferrel home.

It was a story 80 years in the making.

April 7—Good Friday—was the day chosen for the funeral with full military honors, a symbolic day for a homecoming so long overdue. The long dirt road to Newman Cemetery, which is likely often untraveled, was lined on both sides with dozens of American flags.

Words can’t do justice to describe the feelings that swelled within me driving past the flags to park in front of the Newman tabernacle across the road from the cemetery, where I often parked with my Papa Monk for Newman Cemetery cleanup days when I was a little girl. The hearse arrived, and members of the Honor Guard carried Ferrel’s stately wooden casket to his final resting place.

As taps was played, then honors and a prayer of thanksgiving for his return were shared, I took note of the bright blue sky, the beautiful day and the approximately 100 attendees who came not to mourn but to celebrate a brave soul being returned to his mother’s side.

People of all walks of life were present. Young and old, from near and far. Some drove more than five hours so that their presence could serve as a thank-you; others brought their young children to impress upon them how special this occasion was.

Jeff Hurt, editor of the Double Mountain Chronicle, asked me and several others at the service, “Why are you here?”

I told him I couldn’t not come. Even as he asked, his voice was almost overcome with emotion. While we didn’t sit down and talk about it, I could tell that he and others gathered shared a calling to honor this man.

In the Newman Cemetery on the afternoon of April 7, 2023, there were no dividing lines—only proud Americans—and for the time there, it seemed as if everything was just right in our little part of the world.

I’m not entirely sure why I felt called to learn more and help share Ferrel’s homecoming story. Maybe it’s the deepened sense of patriotism I’ve developed through many trips to Arlington National Cemetery as a Youth Tour chaperone, or maybe it’s Ferrel’s local connection, his burial in Newman Cemetery—just miles from my home and where much of my family is buried—or it’s a combination of these things. But I was compelled to learn more about him and share. I hope that amid the barbecues, fireworks, parades and days at the lake to celebrate Independence Day, the ultimate sacrifice of a soldier from Sylvester hits home and adds an additional layer of meaning to your celebrations.

Below and in the following you’ll find Roenna Thomas’ presentation and a press release from the Department of Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

The Ultimate Sacrifice

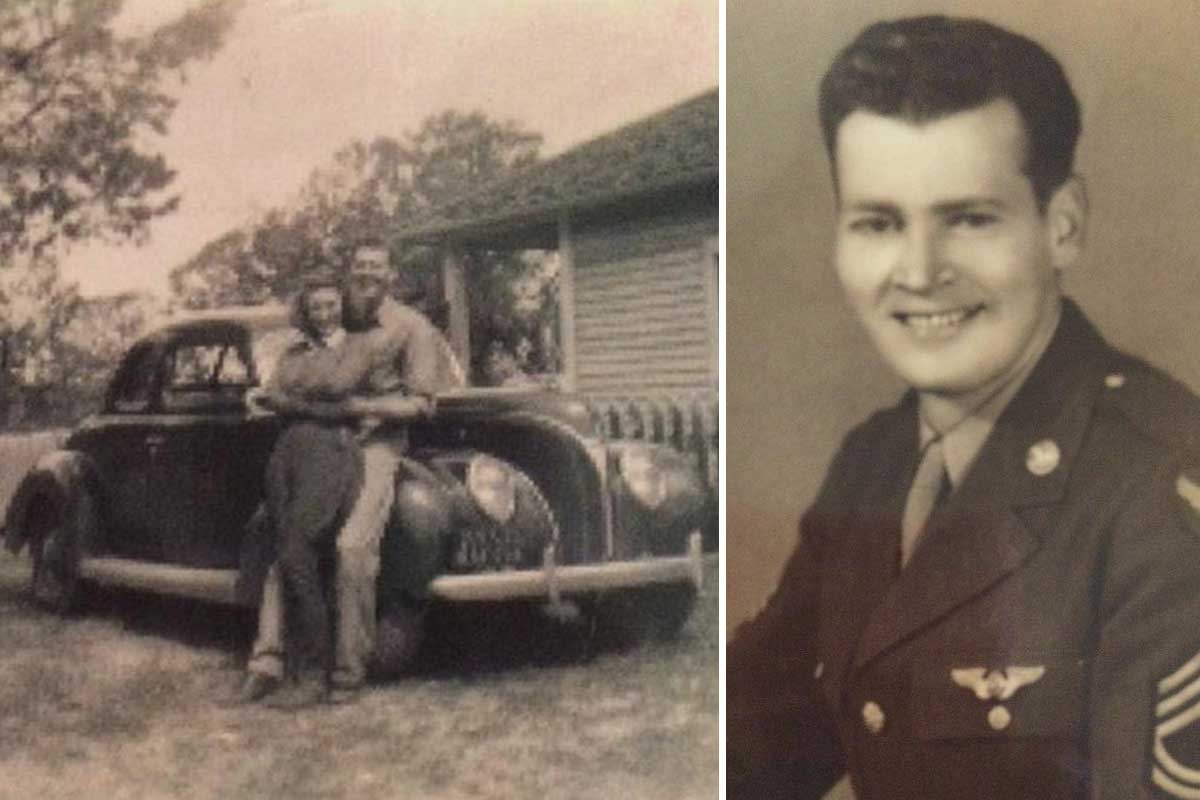

Frank Cross Ferrel was born February 1, 1912, to George W. Ferrel and Clara Jane Cross (my great-grandfather’s twin sister) in Fisher County. Frank graduated from Sylvester High School and attended McMurry University. He married Julia Maurose Putnam on June 3, 1941. They were married in Lueders, Texas, at her parents home. Frank was a teacher in Lueders at that time.

This part of my program comes from an article written in the Fort Worth paper in 1963:

A thundering armada of B-24 Liberators swept across the Romanian countryside at tree-top level, boring toward Hitler’s most productive oil refineries. The target was Ploesti. The date was Aug. 1, 1943. The terrain flashed so near the wings of the B-24s that they could see children swimming in the rivers. Some raiders will never forget that day, others refuse to remember it. The low-level mission was an unorthodox attempt to shorten the war six months by smashing Hitler’s vital oil refineries.

Whether the mission was a success or a failure still is under debate. Losses were so heavy it literally marked the end of the 9th Air Force as a heavy bomber force. Hundreds of Americans volunteered for the surprise thrust, although warnings were issued that half might not return from the bombing run. The mission called for 178 Liberators—manned by 1,763 Americans, a Canadian and an Englishman—to fly 1,200 miles into enemy territory without fighter escort and at a ground-hugging altitude to stay beneath German radar.

When the results were in, 53 of the four-engine bombers were lost, 446 crewmen were killed or missing, and 120 were wounded. The raid shortened the war not by six months, but by days, because the Germans had taken emergency procedures to put the refineries back into production almost immediately after a full-scale attack.

History takes a hard look at Ploesti, one of the war’s most thoroughly rehearsed battles. Because of the low-altitude attack, special perspective charts showing terrain from 50 feet up were prepared for the navigators, and intensive low-level training was conducted near Benghazi, Libya.

Planners theorized the low-level raid would keep the force of Liberators below German radar and predicted defenses around the refineries would be weak. They were also told that their props would cut the steel cables connected to the barrage balloons. This was not the case. Even the takeoff was almost suicidal.

The Liberators stirred up a mammoth, man-made duststorm as they took off at two-minute intervals from their Libyan bases and swung into formation 100 feet above the Mediterranean for the flight to Ploesti. The lumbering bombers—heavily overloaded with fuel and bombs—struggled to become airborne. One ship lost an engine and crashed, killing eight. Another Liberator—this time the bomber carrying the lead navigator—was lost during the low-altitude Mediterranean crossing. The airplane wobbled and dipped into the sea. Someone may have clipped his wing, but at low altitude, there was no chance to recover.

Colonel K.K. Compton assumed the lead position. He made a navigational error and turned too early for Ploesti. Some pilots followed Compton, while others continued to the correct turning point, scattering the attacking forces. Compton, now a major general and chief of staff at SAC headquarters, caught his error and corrected it, approaching Ploesti from the opposite side. The maneuver kept his group away from direct runs over the city but left them in the battle area for more than half an hour. It was a navigational error, but a major one.

Despite all precautions of the raiders—including the low-altitude water crossing and flying through ravines in drizzling rain—the Germans had spotted the Liberators shortly after takeoff from Benghazi. Intelligence reports had been incorrect concerning Ploesti defenses. When the bombers dipped to zero altitude to dump their bombs inside the protective refinery walls, the raiders found themselves in the heaviest flak concentration in Europe.

Haystacks popped open, and railroad cars collapsed, revealing concealed weapons. The short-fused guns spread a highway of flak in the path of the B-24s, riding the steel cables up 100 feet before friction ignited the gasoline and the planes exploded. As the Liberators roared across the city, explosions wafted some of the 30-ton bombers about like leaves in a whirlwind.

The actual battle lasted only about half an hour, but in that time, more firepower than two Gettysburgs was exchanged and five men earned the Medal of Honor.

Upon return to his base, one pilot discovered how low his low-level bombing actually had been. “A chicken was plastered against one of the engines,” he said.

Frank Cross did not survive the battle. His nephew, Simon Ferrel Terrazas, son of Frank Cross Ferrel’s sister, Claudine Ferrel Terrazas, was contacted recently by the U.S. Air Force stating his remains have been identified. Interment will be at Newman Cemetery in the community where he grew up.

Finally Home

Editor’s note: The following is a March 8, 2023, press release from the Department of Defense.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency announced today that U.S. Army Air Forces Tech Sgt. Frank C. Ferrel, 31, of Roby, Texas, killed during World War II, was accounted for January 10, 2023.

In the summer of 1943, Ferrel was assigned to the 328th Bombardment Squadron, 93rd Bombardment Group, 9th Air Force. On Aug. 1, 1943, the B-24 Liberator bomber Ferrel was an engineer hit by enemy anti-aircraft fire and crashed during Operation Tidal Wave, the largest bombing mission against the oil fields and refineries at Ploiesti, north of Bucharest, Romania. His remains were not identified following the war. The remains that could not be identified were buried as Unknowns in the Hero Section of the Civilian and Military Cemetery of Bolovan, Ploiesti, Prahova, Romania.

Following the war, the American Graves Registration Command, the organization that searched for and recovered fallen American personnel, disinterred all American remains from the Bolovan Cemetery for identification. The AGRC was unable to identify more than 80 unknowns from Bolovan Cemetery, and those remains were permanently interred at Ardennes American Cemetery and Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery, both in Belgium.

In 2017, DPAA began exhuming unknowns believed to be associated with unaccounted-for airmen from Operation Tidal Wave losses. These remains were sent to the DPAA Laboratory at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, for examination and identification.

To identify Ferrel’s remains, scientists from DPAA used anthropological analysis. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis.

Ferrel’s name is recorded on the Tablets of the Missing at the Florence American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Impruneta, Italy, along with others still missing from World War II. A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Ferrel will be buried in Sylvester, Texas, on April 7, 2023.

For family and funeral information, contact the Army Casualty Office at (800) 892-2490.

DPAA is grateful to the American Battle Monuments Commission and to the U.S. Army Regional Mortuary-Europe/Africa for their partnership in this mission.

For additional information on the Defense Department’s mission to account for Americans who went missing while serving our country, visit the DPAA website at dpaa.mil or find us on social media at facebook.com/dodpaa or linkedin.com/company/defense-pow-mia-accounting-agency.