Many Texans swear this is the best time of the year. This has nothing to do with the promise of cooler days, back to school and harvest time on the farm. It’s about the autumnal return of an institution that many believe more than any other—more than barbecue, baptisms and boot-scootin’ dance halls—helps bond the citizens of small-town Texas: high school football.

As any true Texan knows, football isn’t just a game played by teenage schoolboys. It’s about a community rallying together for a common cause. The oft-used metaphor—that a Texas high school football stadium is a modern-day house of worship—seems apt on Friday nights in many small towns, where Texans young and old and rich and poor come together for a communion of sorts under bright lights. You will find a town’s pride on display, along with pageantry and school spirit and bragging rights. And, you will hear about life lessons, the value of hard work and teamwork, about the gridiron legends of yesteryear, and of people’s hopes and dreams, their victories and disappointments.

We could have gone to many places where football is king, from Allen (which broke ground in 2010 on a $60 million, 18,000-seat high school football stadium) to Zephyr (one of many towns only big enough to field a six-man team). We chose Donna, a largely overlooked place of about 17,000 residents in the lower Rio Grande Valley that cherishes its beloved Redskins. A working-class city and once-vibrant citrus center, Donna’s people remain loyal and proud of its winning tradition and the state title its stars brought home in 1961—50 years ago—still the only state football title ever won by a Valley team.

Our visit to Donna took place during the 2010 football season.

Thursday, November 4, between 3:45 p.m. and 4:30 p.m.: Photographer Will van Overbeek and I arrive in town in the late afternoon to the beat of drums. The marching bands (high school and middle school) and the school mariachi band, with the musicians’ instruments flashing in the sunlight, line up near the

H-E-B grocery store, fronting the down-on-its-heels town square, framed by a smattering of palm trees and whipped by a mighty wind.

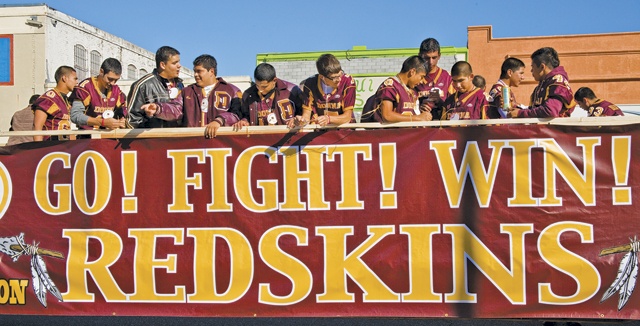

It’s Donna High School’s annual homecoming parade, and you wouldn’t have guessed the Redskins have had a disappointing 4-5 season so far. Swells of people gather along U.S. Highway 83, two and three deep in places, to cheer the team and the twirlers, the banner holders and pep squad members, the cheerleaders and flag bearers and assorted students, parents and teachers who march, walk and ride alongside the horn-blowing, drum-beating maroon-and-gold clad band members and the hodgepodge of homemade floats, decorated by schoolchildren and employees of local businesses.

The football players, wearing their game jerseys, are smiling down from high up in the backs of open-bed trucks.

In a matter of minutes, I’m invited to ride shotgun in a golf cart driven by Dr. Mike Flores, a Donna alum, local medical internist and member of the Donna Independent School District board. My task: throw fistfuls of Tootsie Pops, Jolly Ranchers and other goodies spilling out of a white plastic garbage bag to the kids and grownups along the 1 1/2-mile parade route to the high school, where the bonfire is scheduled.

Somewhere along the way, after we make two stops at convenience stores for more candy, the realization sinks in: This isn’t just a high school football game. This is a coming-out party for this community.

In a little more than 24 hours, Donna will face the Mission Eagles. Despite the Redskins’ lackluster record, Donna pride remains strong in this bedroom community that at one time was home to a Ro-Tel food-processing plant. Today, many jobs have dried up, and many of the headlines in the local newspapers are about border and drug-related violence. Residents say such harsh news belies their family-oriented community, to which the mostly Hispanic residents remain loyal, though many commute to jobs in more prosperous nearby cities, such as McAllen, Weslaco and Harlingen. Donna’s largest employer is the school district, though town promoters have high hopes for commercial development arising from the new Alliance International Bridge spanning the Rio Grande to Mexico.

There’s no question that football is the biggest draw, crowding out economic and political concerns of the day, as the Redskins gear up for their last game of the season (a long-shot chance of making the playoffs disappeared with a loss the previous week).

“Regardless of how bad the team is … it pulls people together,” Donna Mayor David Simmons says. “People might have disagreements, but this is one time when they put everything aside. They unite and support the team on Friday nights.”

Around 6 p.m.: The parade ends outside the football stadium, and I run into Mario Ruiz, a Donna alum and high school history teacher, pep and spirit squads sponsor and exchange-student coordinator. With him are two foreign students, one from Germany and one from Brazil. Neither of the teenagers has seen anything like this show of support for a school sports team. “It’s really cool,” says Felix Borgboehmer, the German exchange student.

Because of the high winds, fire department officials won’t allow the annual bonfire, so the crowd in the shadows of the stadium must be satisfied with cheers and rousing words from players and cheerleaders. Among them: Clarissa Gonzales, this year’s Indian Sweetheart and the closest thing to royalty in the Donna student body. The Donna Indian Sweetheart is the oldest student-elected position, dating to 1934. Each year, the female student who wins the honor is expected to spare no expense on her elaborate costume, collecting donations from family, friends and local businesses.

Gonzales says her costume cost about $2,000, including an authentic headdress made by a Navajo artist and a nearly 10-pound overlay handcrafted by a local seamstress using an estimated 250,000 beads. The first game of each season is dedicated to the Indian Sweetheart, who is presented in all her regalia and paraded around the field as a good-luck charm for the team.

Sometime after 8 p.m.: An enticing aroma—homemade enchiladas—greets us as we enter the home of Andrew Salinas, a senior offensive lineman who invited us for supper. Andrew’s mother, Dolores, just pulled a large tray from the oven. Andrew’s father, Rudy, offers refreshments while he and Andrew keep an eye on a college football game on the flat-screen TV. Rudy grew up in Donna and played on the Donna football team in the 1980s. He works as a marketer for Sysco, the food-service firm. Dolores, who grew up in Harlingen, has also built a successful career, serving as president of the regional Better Business Bureau of South Texas. We’re joined by Amanda, the Salinases’ eldest, who moved back after becoming homesick in San Marcos, where she attended Texas State University. She has enrolled at The University of Texas-Pan American in nearby Edinburg.

“We don’t have college degrees, but we want that for our children,” Dolores says. Rudy adds: “It’s a necessity today.”

We talk about growing up in the Valley, the effect on the football team of opening a second Donna high school (the school board is expected to OK a new secondary school to accommodate population growth, but will it dilute talent?) and whether football helps or hurts students in the long run. The majority opinion: Playing sports probably lessens the school’s dropout rate. Rudy notes that if students “don’t pass, they don’t play,” a statewide rule that was not in place when he attended Donna. But Amanda insists football gets too much attention and draws funds from other sports (there’s not even a swimming team, she notes).

Andrew, who wears the same No. 75 jersey his dad wore, plans to attend Texas State or The University of Iowa and major in history or kineseology. He eventually wants to become a teacher and football coach—here in Donna. “That’s what is most important to me—coming back,” he says.

Around midnight: I explore the largely empty streets of inner-city Donna and pass the old food-processing and packing plants (the faded letters of “Ro-Tel” are still visible on a water tower above brick and metal buildings). I step out to better view a mural outlining the city’s history, lit by a street light across from the nondescript city hall.

I notice a buzz of activity on the outdoor patio of Cedar House Bar & Grill. It’s filled with about 100 Donna grads who have gathered for their 20th reunion. Many of them now live in Houston, Dallas and other cities. The reunion organizer is Joey Garza, a sixth-grade Donna middle school teacher and city council member whose mother and sister helped cater the event. They run a Tex-Mex restaurant in a converted home.

Donna alum Elvira Gonzalez Kaiser, who now lives in Dallas, confesses that she cries when she leaves to go back to Dallas. Why? “Family,” she says, explaining that she has five siblings, parents and 28 nieces and nephews in Donna, mostly living near each other in a collection of houses on Seventh Street.

Accompanying her is her husband of one year, Don, an attorney who grew up and played football for his high school in Topeka, Kansas. “I was shocked when I saw the parade,” he says. “There’s colleges that don’t have a homecoming parade like that. It’s pretty impressive.” He says he also was astounded when he learned that one of his local nephews, a sixth-grader who plays on a middle school team, was watching game film after practice the other day. “When I was in sixth grade, I was watching cartoons,” he says.

Several former football players are standing around, laughing and telling stories. They try to explain how Donna’s football traditions are unmatched elsewhere in the Valley. Donna’s noisy home crowd, with its spectators rhythmically stomping their feet and making chopping tomahawk gestures with their arms, and its drumbeat-playing band, fire up the team.

“It gives me chills,” Frank Villanueva says of coming back and hearing the drumbeats of the band. When you hear that, he says, “You know it’s Donna,” Garza says: “You know it’s home.”

7 a.m., Friday: The offensive linemen, or O line as Andrew Salinas calls them, are having breakfast at the IHOP in Weslaco. The Friday breakfast is a game-day tradition. In addition to Andrew, there are four other linemen filling up on pancakes, syrup and bacon. Andrew and the other seniors talk about tonight’s contest being the last game—not only of the season but also perhaps of their entire lives. They are confident that they can beat Mission, with its 3-6 record, and go out with a win.

Salinas, who stands 5 feet 11 inches and weighs about 220 pounds, is not only undersized to play college ball, but also too slow, he jokes. “That’s running back size, but there’s no running back speed here,” he says motioning to himself, joking that his 40-yard dash is timed in minutes—not seconds.

What will they miss about playing football? I ask. “The smell of the grass, seeing the lights,” says Mark Laballero, a senior offensive tackle, and then with a smile he adds, “Getting screamed at—getting screamed at a lot.” He and others say they won’t miss going over game film with coaches, who use laser pointers to note mistakes they’ve made.

“Oh, I hate film,” says Saul Cruz, a junior.

Just before 9 a.m. I catch Head Coach Manuel Moreno in his cramped office. Moreno, who also serves as athletic director, grew up in Donna idolizing football players, including the members of the 1961 championship team. Fifty years ago, the Donna team came from behind to defeat powerhouse Quanah in the Class 2A state championship game at Memorial Stadium in Austin. The victory is still commemorated on the city’s downtown water tower. Moreno, who has served 23 years as a coach, including the last four as head coach, proudly points to the ’61 trophy, which sits on a bookshelf. He gets it down, and I can see it has become tarnished over the years, its once-shiny golden football dulled with time.

Today is the last day of the second six-week period of the school year. All 48 players on the team are eligible to play, Moreno says, meeting the requirements of the state’s “no pass, no play” rule, which prohibits students from participating in extracurricular activities if they aren’t making the grades. Moreno, an offensive lineman during his high school football days at Donna, says he and the other coaches “keep on them” to ensure that they can play.

Asked about injuries, Moreno notes that sometimes he has kept players off the field for their own good. He says one player continues to dress for games but is not permitted to play because he began suffering headaches. His mother was worried about his continued safety, but couldn’t get him to quit the team. “I told her I was totally supporting her. Sometimes we have to make decisions because we are the adults. We can’t just expect young men to make decisions like that,” Moreno says. He says he told the player: “This [playing football] is only for a little bit of your life, and then you go on. The key is to make sure you have a good education and a good life.”

11:55 a.m.: Donna High School Principal Nancy Castillo greets us from behind her desk. She is a Donna native and served as Indian Sweetheart in 1980 before she graduated and became a teacher and school administrator. She took over as principal two years ago, succeeding her husband, Fernando Castillo (Donna class of 1981), a former football coach and player. Fernando is now assistant superintendent. The Castillos say their local roots are not unusual among Donna staff, which they agree includes an inordinately high percentage of Donna alumni. It is these deep family roots and connections that help keep the faculty tied to the community, which they say gives them strength and helps to uphold traditions.

I ask the Castillos if there is too much emphasis on football, given that 89 percent of the student body is considered low income and qualifies for the government-subsidized lunch program. Wouldn’t it make better sense to spend more money on academics and improve overall educational standards than plowing money into football? No, they tell me, as if with one voice: Football, as well as other sports and extracurricular activities, is vital to keeping students engaged and involved in school.

Nancy cites research showing students are more apt to stay in school if involved in such activities. Fernando says he advises new middle school and high school principals throughout the Valley to “learn the ABCs: Athletics, Bands, Cheerleaders. I tell them you take care of your ABCs, and you’ll be in good shape. If you mess those up, you’ll be in more trouble than anything else.”

The high school, including a separate freshman-only campus, has about 3,100 students, giving it Class 5A status, but that number is undercounted in the first months of the school year when several hundred students travel with their migrant families for farm work. The student body typically rises to hit about 3,400 by January.

3:15 p.m. to 3:55 p.m.: Students fill the gymnasium for the Friday game-day pep rally. They squeeze into the bleachers and compete for the “spirit stick,” given to the most boisterous class. Most join in and unleash ear-splitting sounds when prompted by cheerleaders (wearing cowgirl hats and boots), teachers and the D’ettes—the dance team members. They sway back and forth, dance in place and sing the fight song and the alma mater, the words of which appear on big signs on a wall along with posters (“Beat Mission,” “Cage the Eagles,” “Pluck the Eagles”).

Sometime between 6 p.m. and 7 p.m.: Just outside of the high school, I spot four boys sitting around a concrete picnic table. I learn they are members of the freshman football team that won the district championship by beating Mission the day before. They each intend to play on the varsity team when their time comes. “I’m just waiting for the chance to get out there,” says Austin Nash, the quarterback of the team, motioning to the nearby stadium where the lights have just come on.

“Football is life out here,” says Daniel Guerra, who plays linebacker and fullback. He says all their lives they’ve heard about the ’61 team winning the state title.

“We’re next,” says George Garcia, a wide receiver.

As we walk to the stadium together, yellow buses carrying the Mission team and band pull in and park on the south side of the stadium. Meanwhile streams of fans, mostly wearing maroon and gold, make their way to the stadium as a police car, with its blue and red lights flashing, blocks traffic. Among those entering is a woman who says she graduated in ’68 and now lives in Edinburg. She is walking in with her daughter, sister and niece. “You always come back to the stomping grounds,” she says, carrying a fistful of season tickets.

7:15 p.m.: Coach Moreno huddles his players and coaches in the temporary building adjacent to the field. After a pep talk about how they have prepared for games like this since they were little boys, and how they need to pick each other up and carry on the proud tradition of Donna football, he does what he always does: He leads the team in reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Many players hold hands or put arms around each other. Some squeeze shut their eyes as they mumble the words. After the prayer, players bellow as if exhaling and pound each other’s shoulder pads, slap on their helmets and bolt out the door into the darkness, running toward the lighted field.

7:30 p.m.: The players emerge from a tepee set up in one end zone, running through a cloud generated by a fog machine—another tradition at Bennie La Prade Stadium, also known as “The Reservation.” Depending on whom you talk to, the stadium seats 10,000 or 12,500, meaning it can accommodate about three-quarters of Donna’s population. One of its most conspicuous features: a video scoreboard that provides high-tech graphics and instant replays. It’s plastered with advertisements from local businesses.

After the opening kickoff, the Redskins take the lead on a 50-yard touchdown run. But Mission ties the score on a long pass play and pulls in front 14-7 in the second quarter of what proves to be a back-and-forth scoring affair.

Among those walking the sidelines is Jerry Jones—no, not the owner and notorious micromanager of the Dallas Cowboys. It’s Assistant Superintendent Fernando Castillo. “They’ve nicknamed me—affectionately, of course—Jerry Jones,” he said earlier, confessing that a couple of years ago he was flagged by a referee for disputing a call despite not being an official member of the coaching staff. Castillo elicits no flags tonight, nor is he laughing as he paces like a caged lion during the tense, hard-fought game.

Just before halftime, I catch up with players from the 1961 team sitting together in the packed bleachers on the Donna side of the field. The quarterback of that team, Luz Pedraza, motions to a man on the sidelines, Hollywood filmmaker Frank Aragon, who has spent several days interviewing the old players and their 83-year-old coach Earl Scott, who lives in Harlingen. Aragon wants to make a documentary and possibly a feature film about the ’61 team, later telling a reporter that he is intrigued by the story of how the team overcame prejudice to win the state title. At a time when few teams were integrated, the Donna team was roughly half Hispanic and half Anglo.

The story is recounted in the book Mexican Americans and Sports: A Reader on Athletics and Barrio Life (Texas A&M University Press, 2007). “[A]thletic ability could help increase Mexican Americans’ acceptance among their white peers,” reads a passage from the book. [A reporter wrote in 1931 that] ‘the Mexican children who can show their skill in art, music, scholarship, or physical prowess soon become favorites with the other white children and are wholeheartedly admired by them.’ By the late 1950s, therefore, the Donna Redskins had a history of fielding competitive, ethnically mixed teams.”

Pedraza, among the many champions who still live in Donna, said the players didn’t care about anybody’s ethnic background. They were all poor, scrappy kids who, with the help of their much-admired coaches (one of whom the stadium is named for), pushed each other to excel.

“To me, if it hadn’t been for athletics, there’s no telling where I’d wind up,” Pedraza told me in an earlier interview, recounting how he went to college, played semipro ball in San Antonio and spent 35 years as a coach and teacher. “I might have ended up on the wrong side, too. But it gave me something to do, to be part of a team.”

Other members of the team echoed those sentiments, including Richard Avilla—who grew up in a family of 15 kids and played with four brothers—and Fred Edwards, who played linebacker and running back and sometimes worked 12-hour days at his father’s fruit stand before going on to star as a linebacker for The University of Texas at Austin. Edwards, now retired from a state government job and living in Paige, says playing for Donna taught him to “never to quit—never. If you did, someone was going to kick your heinie. And football taught me to get along with people whether I wanted to or not.”

Fourth quarter, after 9 p.m.: With only seconds left, senior quarterback P.J. “Pete” Quiroga throws an 11-yard touchdown pass, and the Redskins tie the score 21-21 with the extra-point kick. Play is extended to an overtime (OT) period, but neither side musters a score in the first OT. They match touchdowns and extra-point kicks in the second OT.

In the third OT, Mission scores first but misses a two-point conversion. With Donna driving to tie the score and possibly win, it’s clear the momentum has shifted in favor of the Redskins. Donna moves the ball forward, the drummers pound out a relentless Indian beat, ever louder and louder, and the Donna crowd stomps its feet and chops the air, with fans using their arms as faux tomahawks. Then—suddenly—a Redskin running back fumbles. Donna holds its breath. A Mission player emerges with the ball. The drumbeats fade. But—clearly—the running back’s knee was down before he fumbled … wasn’t it? The pleas of the exhausted Donna players and coaches to the referees go unheeded. The realization sinks in: The home team has lost. The scoreboard reads: Donna 28, Visitors 34.

As they begin to comprehend their loss, tears roll down the cheeks of some players, including Salinas and other seniors. A cheerleader comforts a crying player, his head on her shoulder. Nearby, youngsters beg for mementos (a chin strap, a sweat band) and autographs from their heroes. Family and friends snap photos of the players, who reluctantly leave the field, but not before touching fingers and fist bumping fans who’ve remained.

10 a.m., Saturday: The game is the talk over breakfast at Danny’s, a downtown diner and popular meeting place. Among the topics: Will Coach Moreno keep his job? This is the first year since he became head coach four years earlier that the team didn’t make the playoffs.

***

Postscript: In January, the school board relieved Moreno of his athletic director duties. He remains head coach but with only a one-year contract. “We take our football very seriously,” Assistant Superintendent Fernando Castillo says in an e-mail, explaining the board’s actions.

Rattling around in my head are the words the coach told me during an earlier interview: “If there are strangers or people coming through the area, we help them out or whatever. We are very friendly people. We’re a humble people and a very proud people. That’s the key about my hometown.”

That—and they take their football very seriously.

——————–

Charles Boisseau is an Austin-based freelance writer.