Armed with a tattered law book and a pair of six-shooters, the legendary Judge Roy Bean doled out a peculiar form of frontier justice in a lawless section of far West Texas during the last half of the 19th century. Photographs show a tough, grizzled old geezer in a dusty black coat. Tales from the life of the manipulative magistrate bridge the gap between horror and amusement.

Before he mounted the judicial bench in Texas, Roy Bean served as a California Ranger with a penchant for stealing the hearts of San Diego señoritas. One such amorous episode nearly cost him his life. With Bean in the saddle, a jealous suitor and others got the jump on Bean, strung him up to a poplar tree, urged his horse out from under him and left the scene. Unseen, the señorita dashed from her hiding place to cut Bean down. He was alive and kicking, but spent the rest of his life with a stiff neck.

After that incident, Bean, who was born in Kentucky, left California and drifted through the Southwest, at one point delivering milk in San Antonio. In time, as the story goes, he decided to increase his take by adding creek water to the milk. This scheme worked until one of his customers found a minnow swimming in a milk bottle.

“By Gobs,” Bean said when the customer confronted him, “I’ll have to stop them cows from drinkin’ outa the creek.”

Bean left town and in 1882 set up a saloon in a shabby railroaders’ tent camp called Vinegarroon—named for a whip scorpion—west of the Pecos River and just north of the Rio Grande. There, he planned to line his pockets with money made selling whiskey. When the railroad came through and whiskey began to flow, disorderly conduct followed, and the nearest law was hundreds of miles away in El Paso. But packed in the bottom of an old trunk, Roy Bean had a solution: a dusty law book—the 1879 Revised Statutes of Texas.

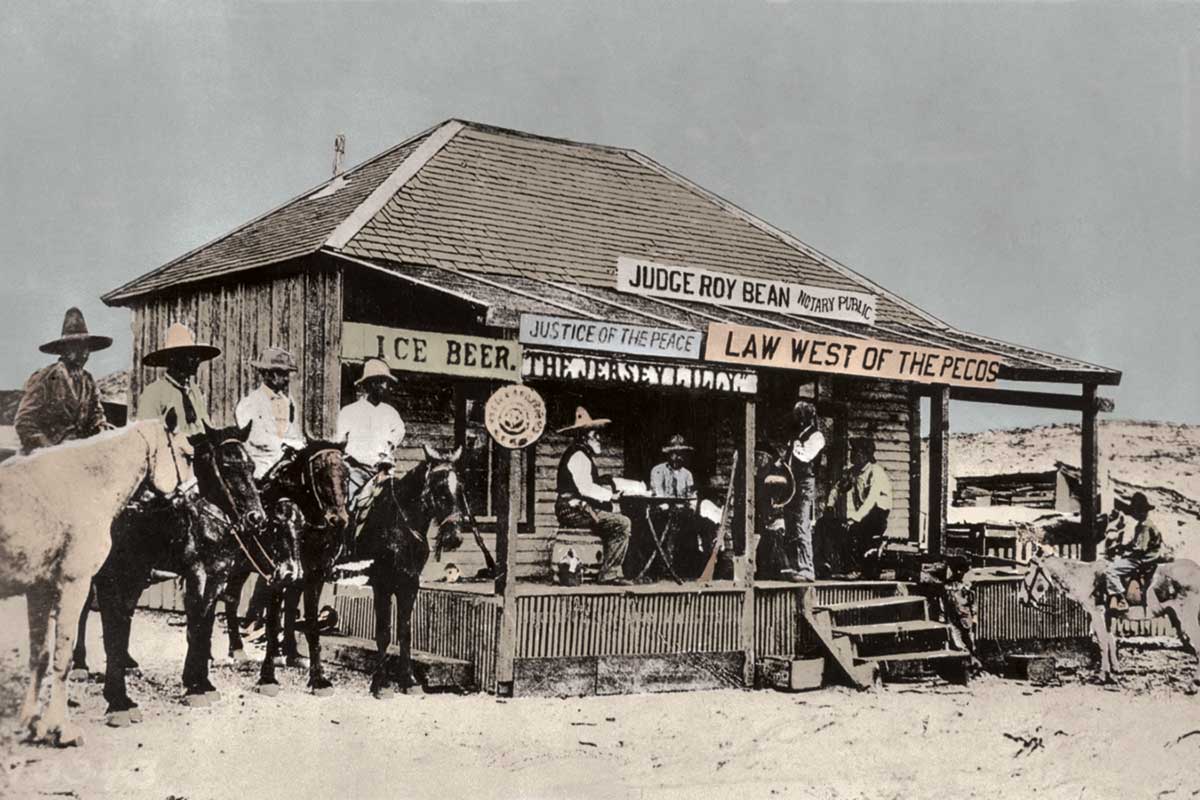

Soon a sign appeared outside the saloon: ROY BEAN – BARREL WHISKEY – JUSTICE OF THE PEACE – LAW WEST OF THE PECOS. Eventually, the judge sent word to the authorities of Precinct 6 that he was willing to accept an appointment to the position of justice of the peace for Pecos County. He got it. With a whiskey barrel for a bench and a gun butt for a gavel, he began to dole out his own brand of frontier justice. Bean’s rulings often had little connection to the statutes in his beloved law book. One handwritten entry read: “cheating at cards is a hanging offense, if ketched.” With no jail in town, the rare prisoner was shackled to a mesquite tree, and justice was meted out in the form of fines, which disappeared into Bean’s pocket.

The tent village, at first called Eagle Nest, was renamed in honor of railroad man George Langtry. Inside Bean’s saloon, an oak bar and poker tables shared space with a crude courtroom. He named the establishment the Jersey Lilly after an English actress, Emilie Lillie Langtry (no relation to George Langtry) of Jersey in the Channel Islands, whose picture he spotted in a newspaper.

Bean, who ignored the correct spelling of Lillie, lost his heart to the beauty. “By Gobs,” he said when he saw the picture, “Ain’t she a purty critter?”

As time passed, murders, robberies, horse thieving, cattle rustling, inquests, marriages, assaults and civil suits all generated income for Judge Roy Bean, who had a tough reputation. He sentenced many criminals to hang, but there is no evidence that he ever actually carried out the threat. He allowed some to escape. Needless to say, they never came back to Langtry.

In his later years, Bean fined a dead man $40—all that the man had in his pockets—for carrying a concealed weapon. But the judge had a softer side that was less well known. The $40 bought a coffin and headstone and paid the grave digger to bury the corpse. And money collected from fines often bought food and medicines for the poor of Langtry.

In 1903, Bean died as he had lived, after a drinking binge. He built his reputation as “The Law West of the Pecos” at a time when West Texas was infested with gunslingers, desperadoes, cutthroats and thieves. The homespun law of Judge Roy Bean worked. And, by Gobs, there are times when the end justifies the means.