Imagine flying over Texas on some warm Friday night this autumn.

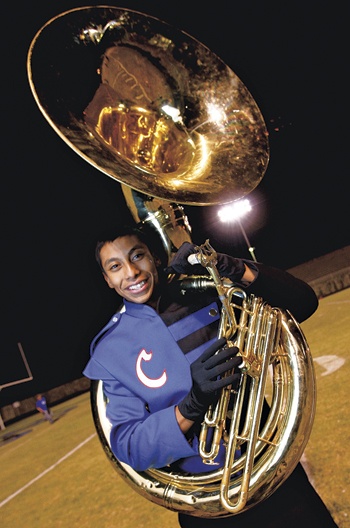

Look down from your window seat and you could easily spot a most interesting phenomenon: all those blazing stadium lights and the buzzing of all the crowds attending hundreds of high school football games simultaneously under way across the Lone Star State. At halftime, you’ll see a real spectacle: uniformed marchers fanning across green fields, forming patterns, drumming beats, blaring horns, flashing flags and twirling batons.

As you hover, consider this: Every Friday night during the fall, an estimated 140,000 young people from more than 850 Texas high schools dress up in crisp uniforms, tall hats with fancy plumes and gawky white shoes, and march and make music for countless fans, family members and townspeople.

We all know that Texans are mad about football, and the players usually get the attention. But what’s a football game without the marching band?

“Yes, you can say that Texas has more high school bands and more participants than any other state. That’s pretty much a ‘no brainer’ when you consider the size of the state and the number of bands,” said Richard Floyd. He’s state director of music for the University Interscholastic League (UIL), the governing body that oversees extracurricular academic, athletic and music contests in the state’s public school system.

Floyd and a chorus of other educators cite numerous national studies showing a link between studying music and improved cognitive skills, higher scores on standardized tests and lower dropout rates.

Texas not only has the most marching bands, but it also has earned a reputation for having some of the nation’s best, with many bands touring the country, winning national awards and sending graduates on to music careers. To be sure, most band members don’t make music their life and may seldom play after they graduate, but band alumni will likely tell you that it was there they learned the skills and habits for success.

With the football season well under way, it’s an ideal time to tune in and learn more about high school marching bands.

Bands in all sizes

Texas marching bands range in size from Class 5A Allen High School’s approximately 650 members, including a drill team and color guard, to numerous Class 1A schools, and others, with 20 or fewer members.

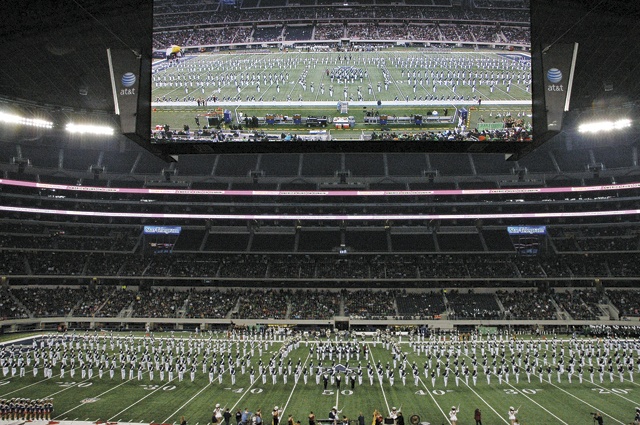

Known as the Allen Eagle Escadrille (French for “squadron”), Allen’s band is considered the largest in the country—high school or college. It’s larger than The University of Texas or Texas A&M University bands, each of which has fewer than 400 members. The Allen band is so large that when it takes the field, it stretches from end zone to end zone. So loud, it can create a wall of sound that has factored in the outcome of games.

When playing at away games, the band requires 20 buses and a team of nearly 100 parent volunteers to help with logistics and other chores, such as moving equipment, chaperoning, handing out snacks and water bottles, and carefully managing plumes that go with marchers’ hats, said Tim Carroll, spokesman for the high school and also a band parent.

The band, still growing in a district with a single 5,000-student high school, has more members than the U.S. House of Representatives. Last year’s band had 59 trombones, and Band Director Charles Pennington has promised if it reaches 76 he’ll add the show tune “Seventy-Six Trombones” to the playlist.

In contrast, Kenneth Griffin, executive secretary of the Texas Association of Small School Bands, said some of the smallest bands have about a dozen members. Griffith’s organization was formed in 1991 to better represent small schools at band competitions.

At some small schools, roughly half the student body is in the band. Last year, Sundown High, on the South Plains near Lubbock, won the UIL Class 1A marching band title with 117 band members, including some eighth-graders. The high school’s entire student body was 188, said Assistant Band Director Zane Polson. It was Sundown’s sixth state marching band title, more than any other school in any classification.

Polson said the community’s strong support and high expectations motivate band students. “In some places, being in the band is not the in thing; it’s not cool. It’s cool to be in the band in Sundown,” he said.

Geeks and nerds

At some places, band members are labeled “geeks” or “nerds.” Usually good-natured ribbing, such teasing may help members rally around each other to form one of the strongest subcultures within high schools.

“You have your preps, your jocks and your band nerds,” said Jolynn Harwell, 24, who played clarinet and served as drum major for two years at Stephenville High School. She now teaches English at North Garland High School, where she also serves as unofficial adviser to clarinet players. “We always called ourselves ‘band nerds.’ I don’t think it’s derogatory or anything. It doesn’t bother me one bit.”

Band kids bond by hanging out together in the band hall; enduring seemingly endless rehearsals, particularly during the grueling summer band camp; engaging in all sorts of fundraising activities; and sharing many experiences outside the classroom on long bus trips to games and competitions.

“It’s like camaraderie,” Harwell said. “For four years, it’s your family.”

Of course, none of this means there isn’t plenty of friendly competition among players in different sections. Carroll, of Allen High, remembered his son, John, a horn player, coming home from his first day of summer band camp and having already been indoctrinated by the upper-class horn players in his section. He blurted out gleefully: Flutes stink!

Travel: Band members go places

Going on trips is a big draw and a tradition.

The Duncanville band has played concerts at Carnegie Hall, Washington’s Kennedy Center and in Japan, and marched in London and at Walt Disney World.

The Allen band has played every place from the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California, to the new Cowboys Stadium in Arlington.

Alumni of the Rockdale band still talk about their 1980 trip to Mexico City, which amounted to the first airplane flight and visit to a foreign country for most of the students. All 140 students in the band made the five-day trip, during which they performed many times, including at a large soccer stadium, said Don Thoede, the retired band director.

One of the students on that trip was Connie Ahlefeld, who wrote in an e-mail: “I remember all the hard work we did as a group to earn money: car hopping at Sonic for tips, selling stuff door to door, washing cars, etc. And, I think that’s why high school bands are so great—one of the best ways to learn teamwork.”

Leaders of the band

As you might expect, bands are only as good as their leaders.

Some bands have suffered because of revolving band directors. Childress High, a Class 2A school in the Panhandle, saw its band membership drop in recent years after its longtime director retired for health reasons and a new director lasted less than a year. The next director, hired in 2007, made strides to rebuild the program, but in May he made the sudden announcement to leave for another school.

“The whole band is pretty disappointed,” said Shane Statham, a sandy-haired senior and band member since junior high. Like many students at small schools, Statham is involved in multiple activities, including playing on the football team’s offensive line. This means at halftime he marches and plays his trombone with the band while his football teammates are in the locker room.

In contrast, there is the band at Duncanville, a Class 5A school south of Dallas, that has become a music program powerhouse, winning state marching band titles three times and numerous other competitions as part of its comprehensive music program. The 350-member band was directed for 30 years by Tom Shine, who announced his retirement in May. Within weeks of his announcement, 70 current and former students sent letters to fill a scrapbook about how much Shine meant to them.

“Almost every single one thanked Dr. Shine for preparing them for life and teaching them all of these things about having pride in your organization, putting everything into what you do, and that awards and honors don’t matter if you do those things,” said Brooke Ballengee, a senior oboe player.

Ashley Stephens, a flute player who graduated in 2000, wrote: “He wouldn’t let us settle for a level below what he knew we were capable of and would just continue to work on the sections of a piece that needed improvement until they were better.”

Stephens, 28, who now lives in Flower Mound, works as a project manager at a research and development firm. After high school, she earned a bachelor’s degree in biology and chemistry and last year a master’s degree in business administration.

“I think being in band in high school kept me focused and prevented me from getting caught up in the wrong groups of people,” she said. “I like being challenged and excelling, and that carried on for both of my college degrees.”

Now married and expecting her first child, she seldom picks up her flute anymore; when she does, she plays in private, disheartened that she cannot play as well as she did in high school. Even so, she insists there is one thing she never will do: “All I know is: I’ll never sell my instrument.”

——————–

Charles Boisseau is associate editor of Texas Co-op Power. You can reach him at (512) 486-6226 or [email protected].

<!–

Editor’s note: What do you remember about high school band? Share one of your fondest—or funniest— stories below or send an e-mail to the editor.

–>