During my time as a staff writer at The Washington Post some years ago, I also taught a journalism course every semester at George Washington University. One morning in class, I happened to mention that I had crafted something of an unofficial beat I called “eccentric Texans.”

A young woman remarked, “Gee, Mr. Holley, you sure must be busy!”

I suppose I was.

There was something about my native state that seemed to lend itself to individuality, if not necessarily eccentricity, whether I was writing about big-time politicians, athletes, show people, even a renowned lady wrestler from Amarillo.

If they were Texans, chances are there was a particularity about them that defied predictability.

Living in D.C. and working at The Post, I was still a Texan. The place where I was born and where I had lived most of my life was in my bones, in my blood. I couldn’t shake my Texas identity any more easily than I could smooth out my Central Texas twang. It gradually dawned on me that when I wrote about Texas, I wrote with more authority, more concreteness, more feeling for the place and its people. I decided to come home—home to Texas.

My return meant coming home to family, literally and figuratively. Once again covering the immense expanse of Texas as a journalist, I rediscovered not only the rich diversity of this place but also the shared sense of identity that transcends difference. Whether I’m talking to a Panhandle rancher near Lipscomb or an East Texas teacher in Kirbyville, a Gulf Coast shrimper out of Port Isabel or a West Texas nurse in McCamey, I know—and they know—that we both are Texans. This place has shaped us.

Black, brown or white; man or woman; old or young—we’re family. Like your kinfolks and mine, we don’t always get along, but as Texans we share an identity and an abiding respect for what we have in common. We know each other well.

—Joe Holley

Jay B Sauceda is an entrepreneur and photographer whose book A Mile Above Texas features 150 photos of Texas taken from a Cessna 182T. Sauceda was raised in La Porte.

Jay B Sauceda

Jay B Sauceda

“The moment I knew what it meant to be Texan was the evening my wife and I were invited to watch George Strait play a private show at Gruene Hall a few years back. There were all kinds of people in the room—professional wrestlers, songwriters, regular folks, you name it. The random group of people came from all walks of life to see and hear King George. It was the epitome of ‘Texanness.’”

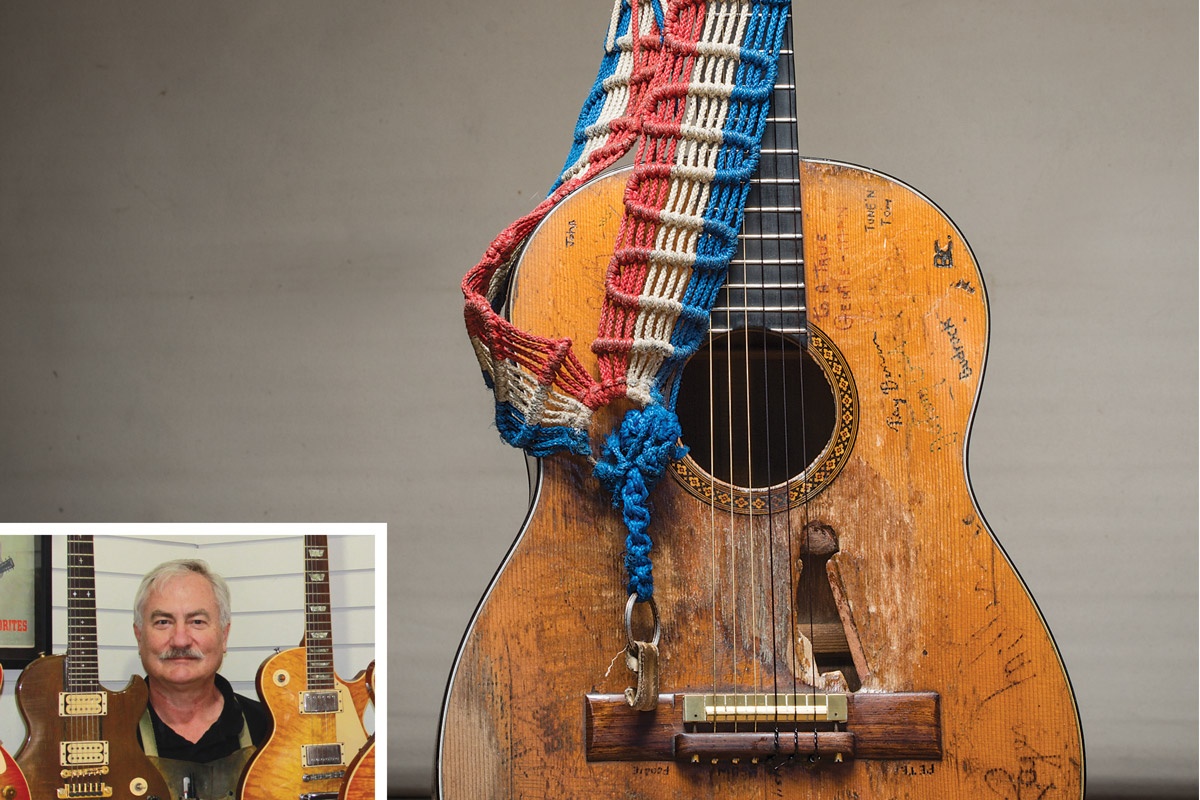

Mark Erlewine first fell in love with Texas when he visited with friends from high school in 1967. He moved his guitar shop to Austin from Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1974.

Guitar: Wyatt McSpadden. Erlewine: Courtesy Mark Erlewine

Mark Erlewine

He has made music for decades, though you’ve probably never heard Mark Erlewine play. He’s a luthier—a repairer and creator of guitars at his shop in Austin. A badly mangled instrument affirmed his karma as a Texan, though it’s not the threadbare acoustic guitar for which he is legendary.

“I was in my shop about 20 years ago, when a man and woman, decked out in full Texas attire—jeans, cowboy boots and hats—came in with a large black garbage bag holding the pieces of a Martin guitar,” Erlewine says. “The man explained that she had put the guitar over his head during one of their arguments, but since then they had started counseling to mend their relationship. They told me part of the process of putting their relationship back together was to have the guitar put back together.

“I was able to mend the guitar and can only hope their relationship has fared as well.”

There’s no question about the love story of the other guitar—Willie Nelson’s Trigger. Willie’s pick and fingernails have carved a gaping hole in the spruce wood of his Martin N-20 classical guitar.

The strains of that relationship fall to Erlewine to mend, and as he has since 1976, he lovingly and tenderly nurses Trigger. Reunited with Willie, they continue a love story that has enraptured a state and changed its musical history.

Tiffany Chen, who, with husband Leon, started Tiff’s Treats in 1999 in an Austin apartment while they were students at the University of Texas. Today the cookie and brownie delivery company has 46 locations in Texas and operates in Atlanta, Nashville and Charlotte.

Bluebonnets: Eric W. Pohl. Chens: Courtesy Tiffany Chen

Tiffany Chen

“Stopping the car immediately to place down kids and puppies in a field of bluebonnets for pictures. Could there be a snake in there? Sure. But the pictures are worth it.”

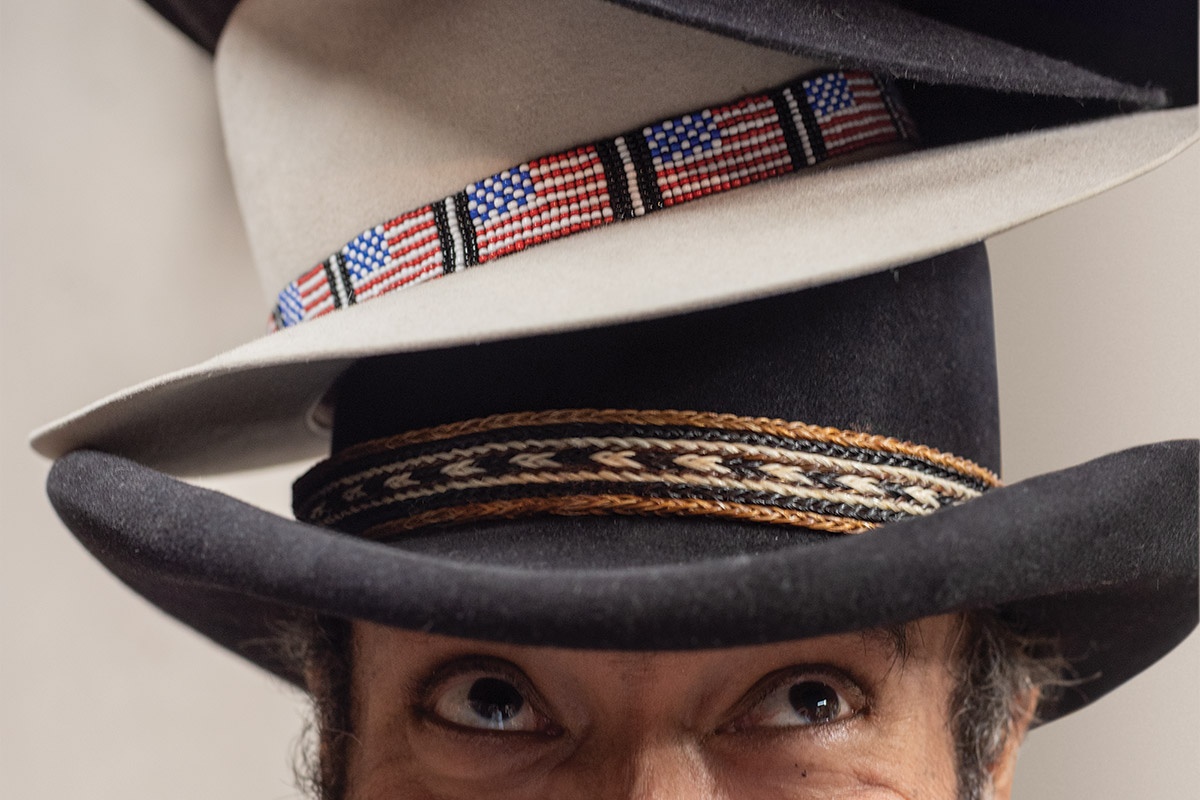

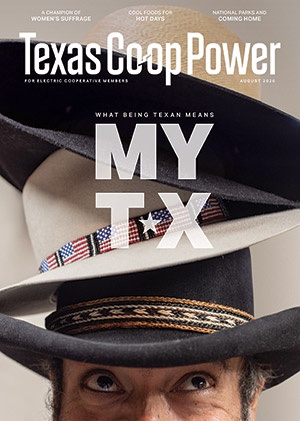

David Torres and Joella Gammage-Torres operate Texas Hatters in Lockhart. Many Texans will remember the original Austin location on South Lamar Boulevard.

Hat: Wyatt McSpadden. Couple: Courtesy Texas Hatters

David Torres

“Stevie used to sit there and play for tips to pay for getting his hat blocked,” David Torres says, gesturing toward the two-seat shoeshine stand by the front door of Texas Hatters in Lockhart. “We modified the flat top and named it the SRV.”

Not every celebrity gets a Texas Hatters style named for them. There is no Prince Charles or Pierce Brosnan or George W. Bush. Stevie Ray Vaughan did get the SRV.

Torres apprenticed at Texas Hatters when he met the owner’s daughter, Joella, who later became his wife. She represents the third generation to operate the celebrated business, which moved to Lockhart from Buda in 2006.

“I grew up in the shop,” Joella says, “and making a hat is like making a sculpture.”

David Torres and Joella Gammage-Torres operate Texas Hatters in Lockhart.

Many Texans will remember the original Austin location on South Lamar Boulevard.

Bernard A. Harris Jr., a physician, former astronaut and the first African American to walk in space. The Temple native is CEO of the National Math and Science Initiative in Dallas.

Capsule: NASA.gov. Harris: Courtesy NMSI

Bernard A. Harris Jr.

“I have logged more than 438 hours and traveled over 7.2 million miles in space. No matter where I traveled and lived, I have always returned to Texas.”

Tom and Lisa Perini own the legendary Perini Ranch Steakhouse in Buffalo Gap.

Wyatt McSpadden

Tom Perini

“We’re proud to be Texans,” says Tom Perini, who with his wife, Lisa, owns Perini Ranch Steakhouse. “We’re out here in the real Texas, surrounded by wheat and cattle.”

They share the story of the day four men in suits came in. “They were looking around and made me nervous. I thought they might be insurance inspectors or something,” Tom says, “so I went over and sat down.” It turns out the four were developing a steakhouse concept for a restaurant chain.

“What do you do to make this place so Texas?” one asked.

“We don’t,” Tom answered. “It is.”