After my mother’s funeral, I put off returning to the cemetery as long as possible—indeed, until I began to hear her saying in an exasperated tone of voice: “Two years, I’ve been gone. It seems you’d at least want to see if my headstone is in place.”

I knew exactly what her headstone looked like, but I finally got in the car and made the 80-mile drive from Austin to Fredericksburg. I turned off Main Street and headed north on Texas Highway 16 to the Greenwood Cemetery, which dates back to 1898. Post oaks and blackjack oaks line the 20-acre cemetery just north of town. Away from the cemetery’s paved roads, its narrow, gravel ways are like quiet country lanes.

Greenwood has a silk-stocking district where affluent families rest in small mausoleums or in enclosed terraces surrounded by rock walls. They remind me of House & Garden magazine photo spreads from the 1950s.

My parents had chosen to be buried in a newer section, which is like a lawn with flat, minimalistic headstones. Confident that an inner compass would guide me to them, I started across the grass, but when I arrived at our row, the graves weren’t there. I moved to the next row, looked around, then to the next. Bewildered and beginning to panic, I was reduced to that most unnerving state of childhood: I had lost my parents; therefore, I was lost. Had a nearby grave been open, I might have toppled in, but then, looking down, I noticed a familiar name carved on a stone: one of my mother’s friends and one of my junior high teachers. If she was there, then I couldn’t be very lost.

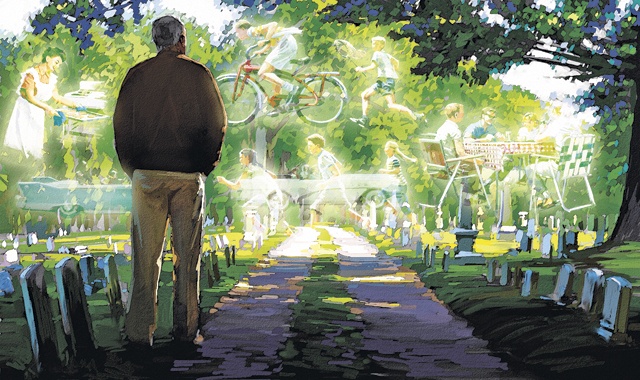

Calmer, I saw that I was in the wrong section of the cemetery. After finding our graves, other familiar names drew me from one headstone to another. I was surprised by how many people I knew, such as my friends’ parents and some of my friends. The past came back to me, all of the names and stories, the overlapping lives, the romances, the intertwined tragedies. The town I’d known was there, an entire community.

In most cemeteries, there are many competing narratives. There are the stories of the individual deaths, which are often sad, if not tragic. Then, there is the larger narrative that the surviving community tells by creating a place of peace and order.

Fredericksburg had seemed like a separate world when I was a child—safe, confined, yet somewhat strange. There were, of course, two languages—German and English—and my family spoke only the latter. There were two cultures, and, without quite realizing it, we were in the minority. We lived on a block that people in Fredericksburg called “little America” and that we referred to as “the neighborhood,” and by that we meant four families—the Coxes, the Browns, the Lawrences and the Davidsons.

Our parents had all come of age during the Depression and World War II and wanted our lives to be ideal. The mothers stayed home, baking cookies and organizing Scout troops and PTA events. The fathers came home for lunch. At noon, you could hear the town stop for the midday meal, the clatter of knives and forks; you could smell the food. In the long, cool Hill Country evenings, the parents would sit together in lawn chairs, while the children played hide-and-seek, chased fireflies or lay on quilts spread on the lawn and looked up at the stars.

In the summers, we rode our bicycles to the public swimming pool or to the public library, which was housed in the octagonal-shaped Vereins Kirche, Fredericksburg’s first public building. Its polished granite and marble floors were cool no matter how hot it was outside. Our world was so small that I always scanned the library checkout card inside a book to see who had read it and was aware that someone would do the same and see my name.

In high school, we drove up and down Main Street as though we were tethered on an invisible leash. We would cruise through the Dairy Queen or The Tower to see who was there, but we would always turn back at the same place at either end of the street. We were innocents, raised to believe that government should be respected and that we lived in a fair society. We didn’t know what lay beyond, didn’t realize we could break the gravitational pull of Fredericksburg. Only one car kept going, the three boys sailing all the way through West Texas on their way to California.

I found the graves of two classmates, then walked back to my car, stopping again at my family’s headstones. I’d never noticed how the much the cemetery was a reflection of the town or considered what a spell graveyards cast upon the living.

But that is part of their intended function, to pull the living back to the dead, to create a sense of continuity and meaning to help us confront the mystery of life and death.

——————–

John Davidson is an Austin-based writer.