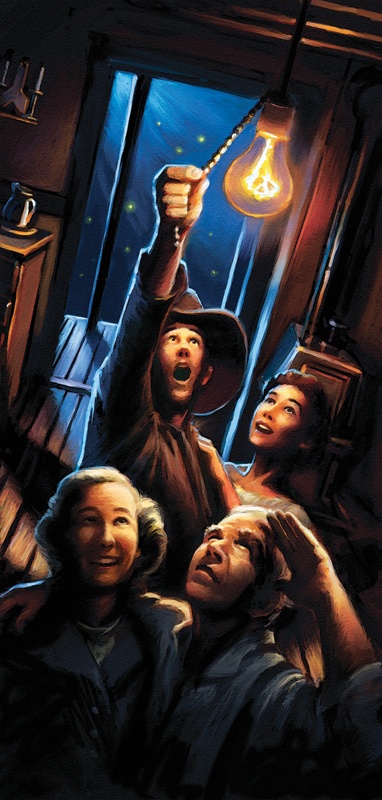

The sun had set more than 30 minutes earlier, and the room is all but dark. Barely enough light filters through the screens to silhouette the four people congregating in the middle.

“OK, Ellie, grab this chain and pull on it—not too hard.”

With an audible “click” from the ceiling, she can now see clearly the face behind the voice, which came from her husband. Standing beside her are a much older man and woman. Each has a turn yanking the chain so they all can see what it’s like to make the dark suddenly give way to light.

“By Ned, what’ll they think of next?” says the older man.

That scene took place in the late 1930s, and I, of course, can only guess at the astonishment expressed over a bare lightbulb. But, safe to say, it must have seemed like a miracle.

Brighter futures for my parents and their neighbors east of Roane became possible with the first meeting of Navarro County Electric Cooperative on November 26, 1937. Within a year or so, they would benefit from the co-op’s initial request to the Rural Electrification Administration for $100,000 to string 92 miles of line. A plus for my mom was the opportunity to attend the co-op’s annual meeting. She enjoyed the socializing and the thrill of winning a door prize.

Mom and Dad married just days ahead of the Great Depression and settled in with her parents on a tenant farm way out in the cotton patches of North Central Texas. For the next eight or nine years, no one in the house paid any utility bills. There were no utilities! Water for the cistern ran off the roof, wood was free if they cut it themselves, and kerosene came in a can from the general store. Even after they clicked on that first light, my parents never paid an “electric” bill. They always called it the “light” bill.

Makes good sense. When the REA high line tied into their house, a few lights were all they had to turn on. For a while, that was enough to marvel over. And this convenience came with a bonus—light from a wire instead of a fire. After the switch, they no longer had to worry about knocking over a kerosene lamp and burning down the house. They’d lived through that horror several years earlier.

Yes, Depression-era people always seemed to carry a special reverence for one of the simplest electrical devices—the incandescent bulb. But they gladly welcomed other conveniences that followed. For my parents, the first was a refrigerator to replace the icebox, much to the dismay of the ice deliveryman. Dad rolled a wringer washer onto the back porch in 1945, making it easier for Mom to wash the diapers she kept pinning on a new baby boy.

I was old enough before we moved to Dad’s home place, in 1951, to take note of two other plug-ins at the rental house. One was a boxy AM radio stationed on a table in a corner of the living room. With programs like “The Lone Ranger” or “Fibber McGee and Molly” on the air, the radio was a magnet. It seems that to listen to the radio back then, folks also had to be able to see it. The new addition replaced a battery-powered console receiver, which very likely joined the laundry washboard as a castaway.

The same fate awaited the paper funeral-home fans that had been my family’s only defense against the sweltering summers. Instead of burning calories to keep the fan fluttering back and forth, they plugged in an Emerson oscillating fan and let it stir the hot air around. It worked pretty well if they were close enough for the moving air to evaporate their sweat.

Refrigerator, washer, radio, fan—all making life better and the meter run a little faster. Still, my parents paid the light bill and continued to do so even while plugging in more and more conveniences in the newly remodeled home place. The first appliance to go on a new kitchen counter was a Sunbeam Mixmaster, which I still have!

It has plenty of company. In my current home, I’ve counted no fewer than 62 devices that require an outlet. And every time I thought I was finished, something in the back of a cabinet (heating pad) or outside in a closet (soldering iron) came to mind.

Many items in my inventory are electrified versions of things that have been around for a good many decades: iron, sewing machine, saw, coffee pot, guitar, even a pencil sharpener. My parents, from a pre-REA perspective, would see many of today’s plug-ins as a newfangled replacement for something they had sweated over.

Mom and Dad did live long enough to at least hear of a personal computer, but it had no place in their universe. “All I need is this journal and a sharp pencil,” Dad might say. And if they could walk into my house now, one of them would surely ask about that black thing with all the blue and green lights over on that table. Well, Mom, it’s a router. What’s it for? Well …

So what’s next? It’s a safe bet that right now some visionary is pecking on a computer or tinkering in a shop as he or she perfects the next big thing to plug in. Or

it might even be a little thing. Whatever the scale or size, years from now the fruits of that genius will make some task easier or faster or safer. Maybe we’ll be around to buy one. In spite of our imagination,

it could be as foreign to us as a router would have been to my parents. But it will happen, and that new wonder, like all the others, will help make our lives better in some way.

As long as we keep paying the light bill.

——————–

Richard L. Fluker lives in Marshall.