Familiar strains of “The Blue Danube” waft through an open-air pavilion in the South Texas village of Rio Hondo, while teens in summertime flip-flops, baggy jeans and sports jerseys pair up in a ragged circle.

Joel Rodriguez, a burly high school football player from Houston, seems to be the unlikely waltz master.

“Hey, pay attention! Start again until we get it right,” he admonishes, as nine couples stoked on Cheetos and orange soda groan good-naturedly. He reminds the group—including in particular one Sara Marie Sanchez, age 15—that a roomful of family and friends will soon be watching.

Later, Rodriguez laughs as the group scatters for hair appointments and tux pick-up. “I just made the steps up,” confides the 17-year-old junior. “I’ve been to these things before. It looks really good when the girls have their dresses on and they all turn at the same time. I just want them to all spin at the same time.”

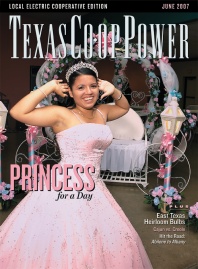

And sure enough, only a few hours later, all eyes are on Sara and company as they step out confidently from beneath a castle-themed arbor trimmed in mini-lights and roses. Sara is reborn in floor-length pink tulle, sparkling tiara and cascading curls. Her entourage is resplendent in pink bowties and cumberbunds, or sophisticated one-shoulder sheaths and strappy sandals.

The way they dance and spin, you’d never know they learned the steps yesterday.

It’s all part of a time-honored coming-of-age ritual for Hispanic girls that dates back to Aztec times and now waltzes smoothly into the 21st century. Called a quinceañera, it combines religious observances with an all-out social extravaganza that has fueled its own retail industry and often pulls the entire extended family into the planning—and paying—process.

From the Spanish words quince for 15 and años for years, a quinceañera is meant to symbolize a young girl’s transition from child to adult, and to acknowledge her thanks for the life she has been given. In many families, it is reason for a massive family reunion and an excuse to invite virtually everyone they know to a special dance and party. Even though she lives in Houston, Sara celebrated her birthday in the Rio Grande Valley, where her family is rooted.

Customs differ around the country, but basic ingredients are the same: A formal gown for the honoree, usually in pink or white; up to 14 of her best female friends, cousins or other relatives, a.k.a. the damas, in matching dresses; a like number of chambelanes or escorts, also dressed for the occasion; a big cake; ceremonial gifts such as a prayer book, doll or religious medallion; a church service; and a choreographed dance at the party to follow.

Limousines and a big photo in the newspaper are not uncommon.

“To me, a quinceañera would be like something a girl dreams of. Something she can look back on when her kids are grown. It’s a lot of memories,” says Sara Flores, who recently helped plan her namesake granddaughter’s big day. “We were all going to pitch in and get her a car, but she said, ‘No! I can have a car later, but a quinceañera comes only once in a lifetime.’”

A home health aide from a modest family, Sara Flores didn’t have a special party when she was 15, but she worked to give her daughters that choice, and now her granddaughter as well.

“She’s a nice girl. She helps my daughter a lot. When my daughter gets home, the dishes are done. Sara deserves this, and we’re trying to make it very special,” Flores says. “There are a lot of people who would say, ‘How come you’re spending all that money?’ But that’s what Sara wants, and she deserves it. If she wants a quinceañera, I will stretch my arm and leg to do it.”

And if any family deserved a big party, it was the Flores family.

Last spring, Sara’s mother, Elodia Flores, a nurse staffing administrator from Houston, donated a kidney to her 34-year-old brother Luis of Rio Hondo. He had been on dialysis for two years and was in desperate need of a transplant.

“He really didn’t want me to do it because of my kids,” said the single mother of five. “I said, ‘Don’t worry about it.’”

The successful surgery took place two weeks after Easter. It was an emotional experience, but one the family survived, together. Elodia Flores says she counted on her oldest daughter, Sara, to baby-sit and help out in other ways around the house. “We had a hard year. A lot of things happened,” she reflected, a few days before Sara’s party. “Now I would like to celebrate Sara becoming a young lady.”

It’s hard to tell whether Elodia Flores is talking about the surgery or the birthday party: “This is a family event. When things like this happen, we try to stick together and do the best we can for everybody.”

Sara’s quinceañera began with a family barbecue at a park in Harlingen. The meal included brisket, chicken, sausage and all the extras—including music for dancing—for about 100 family members and close friends.

Next was the church service at domed St. Benedict’s in nearby San Benito, where Sara proceeded in with her damas and chambelanes, read a prayer of thanksgiving, and received ceremonial gifts from her godparents and other sponsors.

The highlight of the evening was the dance at Harlingen’s Casa de Amistad event center. Guests brought their own coolers, bottles and snacks to tables decorated with miniature lace- and pearl-trimmed carriages. Sara reigned from a pink and blue rose-trimmed throne, flanked by carriage lights. A constellation of 15 cakes arrayed on an elaborate stand trimmed in matching roses waited nearby.

Once the waltz was finished, pictures taken and bowties loosened for the evening, whoops and laughter greeted a conjunto tune that drew dozens of foot-stomping dancers—from grandmothers to young children—out onto the dance floor.

Pulling it all together, says grandmother Sara Flores, was a group effort. Aunt Pauline paid for the invitations. Uncle José gave the medallion. Other cousins, grandparents, aunts, uncles and friends contributed for the cakes, music, limousine and traditional gifts. Uncle Luis, who also paid for the decorations, stood in for Sara’s father, who was unable to attend, for the ceremonial father-daughter dance.

Today’s quinceañera can be as simple or extravagant as the family that plans it. From homemade barbeque in the backyard to dancing in the shadow of Sleeping Beauty’s Castle, they span the spectrum of expense and can often cost more than a wedding. Even families of more modest means often throw big parties with the help of madrinas and padrinos, the sponsors who help with expenses. Magazines like Quince Girl and Internet sites like www.be15.com offer advice, photos and, of course, retail opportunities.

These days, traditional pink and white have been joined by a rainbow of choices for the honoree and her damas. From Mardi Gras-themed dresses in jewel tones and metallic accents to Victorian lace and pearls, quinceañera ensembles can be as varied as wedding and bridesmaid dresses.

Some families even throw quinceaños celebrations for their sons.

La Especial Bakery in San Benito, a family-owned bakery that has been turning out pastries for 60 years, made the multiple cakes for Sara’s party. Their most popular offering, says family member and quinceañera specialist Alma Ornelas, is the Cinderella theme, with 15 cakes arrayed on a display stand shaped like a carriage, for about $375 to $400. While fairy-tale and princess themes are perennial favorites, Ornelas also recalls Hawaiian and angel-themed cakes, and several topped with Precious Moments figurines or fountains.

But a growing emphasis on extravagance has pushed some Catholic Church dioceses to develop guidelines for this quasi-religious event. The Diocese of Austin, for instance, wanted to tone down the hoopla—an expensive burden for many proud families—and to refocus the event on spiritual matters.

Sister Rose Moreno, who has been director of religious education for 20 years at Dolores Parish in Austin, says her church is one of many that require girls to be active members and attend religious instruction before scheduling a special quinceañera service.

“The Diocese felt there was too much emphasis being put on the dance hall, the music and the dress, and therefore the girls didn’t know the real meaning of why they were coming to church,” says Moreno, who wishes more families would put their money into college funds instead.

Moreno says classes required for girls who want a quinceañera at Dolores Parish try to provide a more solid foundation for approaching adulthood. “They try to give the girl a sense of who she is as a woman, and not only the spiritual part. We talk to them about their decisions in life, how they see themselves as a young person and a young woman in society.”

A quiet high school freshman who “gets along with everybody” and enjoys talking to her best friend, Crystal, on the new cell phone she got for Christmas, Sara Marie Sanchez attended two years of instruction at her Houston church in preparation for her quinceañera. And she wouldn’t have traded it for a car or a college fund.

“Ever since I was 5 years old,” she says firmly, “I wanted a quinceañera.”

——————–

Karen Hastings lives in Harlingen. She has written about the San Juan Basilica and Winter Texans for Texas Co-op Power.