Connie Turner can tell you all about the time she cracked three ribs battling a gate over a cattle guard, slipping on ice in the process. Or about the time an electric meter exploded in her hands, knocking her unconscious. Or the time she injured her foot jumping from a fence.

“And since then, I’ve had shoulder surgery,” she says. “I really think that that injury came from the repetition of pushing on gates.”

But in the last week of her 40-year career at Coleman County Electric Cooperative, Turner can also tell you that she misses working as a country meter reader, despite the toll it took on her body. Seventeen years into that career, she was able to move into an office role, but her injuries weren’t the only factor in that move. Another was the folks on her route. They were like family to her—and aging.

“I could hardly stand to go out there, and they wouldn’t be there anymore,” she says. “A lot of them kind of adopted me. I used to load furniture; I’d get the lawn mower started for them and help them pick their garden. I just did everything that you wouldn’t really think that a meter reader would be out there doing.”

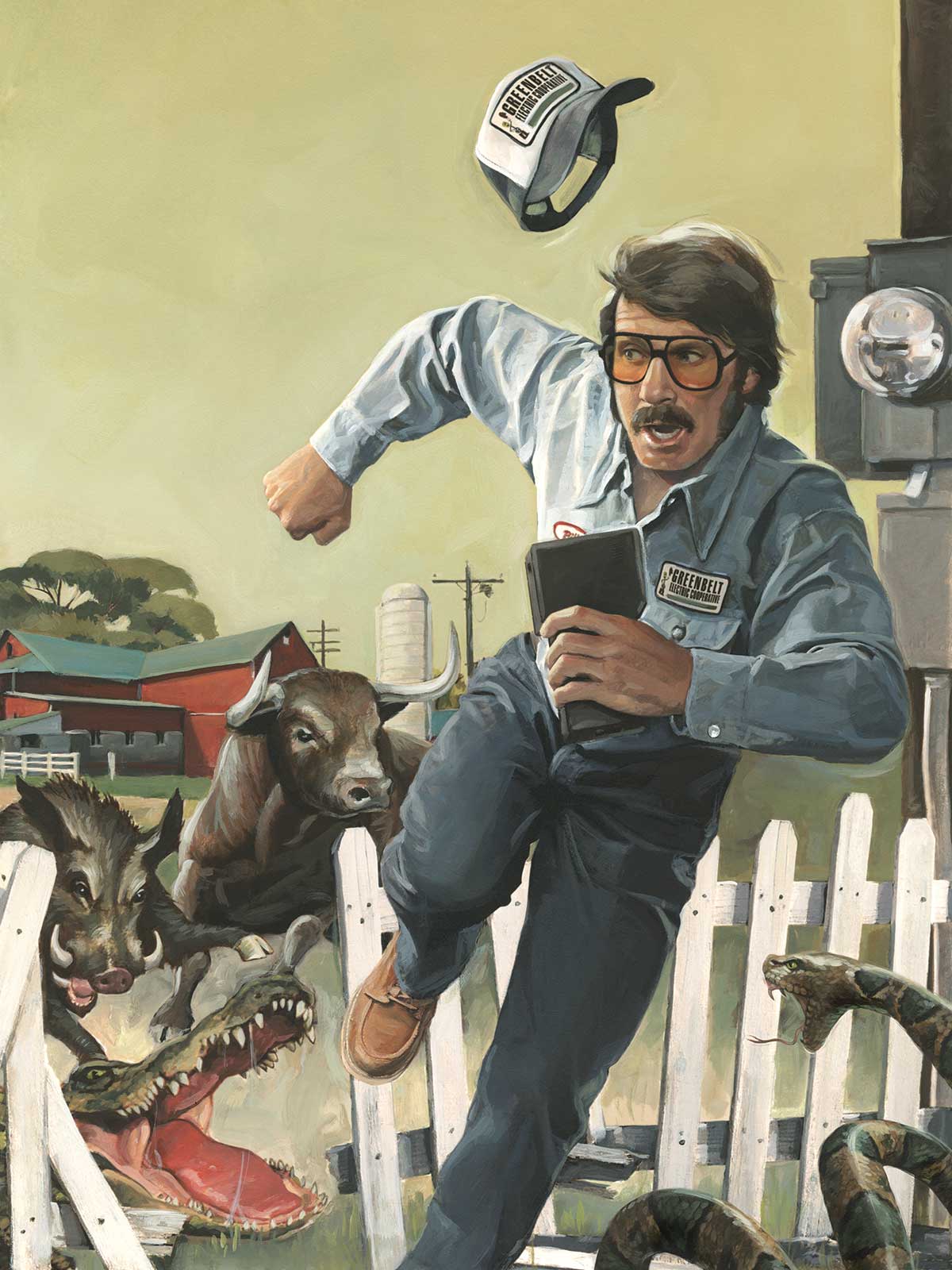

Turner was part of a group like no other—one accustomed to outsmarting dogs, boars, snakes, and the odd alligator or goose; to knowing the roads, power grid and land better than anyone; and to dealing with the occasional unhappy member, flat tires and whatever else came their way as they scoured the countryside, read dials and displays, and relayed kilowatt-hour usage to co-op accounting departments for accurate billing.

But ever since co-ops started installing automated meter reading systems in the 1990s, these neighborly, workaday men and women seemed doomed to be replaced by the very devices they regularly visited.

However, many still haven’t been. Sure, there aren’t as many meter readers working today, but Texas co-ops still employ dozens. And now many of them are armed with more technical skills than ever.

A Good Read

John Gross is one of them. For 19 years he’s been reading meters on his rural routes in Parker County, west of Fort Worth, for Tri-County Electric Cooperative.

“People didn’t know that we still walked around,” he says.

As others in his line of work do, he has plenty of stories. Like the time he tore his ACL climbing a fence to get to a meter—“I actually read about three more meters until I said I can’t keep doing this because I was hopping on the one good leg,” he says—or the time a bull chased him around a meter pole (he still got the reading).

“You don’t know what you’re going to walk into: coyotes, cows, deer, bulls,” he says. “A lot of times you have to run. Otherwise you’re going to have to tangle with some of the dogs.”

Gross says he drives hundreds of miles daily and gets plenty of walking in, but since TCEC started to deploy smart meters across its system in 2019, he’s part of a shrinking team.

Gross, co-worker Bobby Collins and a handful of others at TCEC no longer read all the co-op’s 125,000 meters. Collins has read meters for 23 years in an upscale area closer to Fort Worth, where he’s met celebrities Terry Bradshaw, Sandra Bullock and Josh Hamilton in the course of his work, but it’s the everyday folks who he especially appreciates.

“They’ll start a story, and you’ll end up leaving; and then next month, they’ll pick up right where they left off,” Collins says.

The Future Is Here

Economist David Autor famously pointed out that the invention of the ATM in the 1970s seemed sure to spell the end for bank tellers. But a funny thing happened: As ATMs quadrupled between 1995 and 2010, the number of tellers actually increased over that period.

“The last 200 years, we’ve had an incredible amount of automation,” Autor said in a 2017 interview with CBS News. “We have tractors that do the work that horses and people used to do on farms. We don’t do bookkeeping with books. But this has not, in net, reduced the amount of employment.”

Since the 1990s, when electric utilities began to implement AMR systems, jobs for electric meter readers in the U.S. fell by more than half, from a peak of 55,000 in 1996 to 24,000 in 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Today, nearly all co-ops in Texas have deployed some form of advanced metering infrastructure—a further revolution in metering technology that unleashed myriad benefits for co-ops and their members. But like any complex system, even AMI needs humans to watch over it and fix it when it falters.

When that happens, a worker still has to drive out, find the meter, get a reading and make a fix.

“We generally troubleshoot,” says Kevin Gray, one of two meter readers at Fort Belknap Electric Cooperative. “If we have a meter not sending a reading in, you go out to see: Is the transformer fuse blown? Is the AMR itself dead and not sending a reading? We check transformer connections, look for trees burning on the line.”

As meters have become more complex, so too have the jobs of meter readers like Gray, who has developed new skills to troubleshoot issues in the field.

“I can remember back when the technology began to get a good foothold in the market, obviously the meter readers got very nervous,” says Mike Cleveland, manager of meter products at Texas Electric Cooperatives, the statewide association for co-ops. He says a lot of co-op leaders initially used that as an excuse to delay upgrading to the new meters.

“It took a while for people to understand the benefits and understand that you can take meter readers and turn them into more advanced technicians for running the AMR system,” Cleveland says. “You’re implementing something that has to be babysat all the time. It’s a complex piece of technology that doesn’t just run on autopilot in the background. Somebody has to monitor and manage it.”

More Than Meters

In the 1970s and ’80s, many electric cooperatives started meter reading departments, some citing frustrations with the self-reporting postcards that most utilities of the era relied on.

At Southwest Texas Electric Cooperative, that meant closing the office for about a week every month. Each of the co-op’s employees would grab a pickup, take a meter route and gather readings from rural West Texas. General Manager Buff Whitten did his part when he started at the co-op in 1977.

“You don’t get to see the system like we once did,” he says. “You’re looking at poles, you’re looking at crossarms, you’re able to see the system and recognize problems that you take back, keep track of and correct. And there’s always an opportunity, when you’re out there, to meet the members.”

AMI won’t spot a broken crossarm or start a lawn mower for a member, but these systems of smart meters, communications networks and data management systems can do so much more. The granular data they capture increases reliability by enabling advanced outage management systems and troubleshooting and provides cost savings for co-ops and their members.

“The old mechanical meter, as good as it was, it was pretty dumb,” Cleveland says. “All it could sit there and do was just count revolutions, but these new meters, they just have so much horsepower under the hood. They’re very powerful instruments.”

Meter readers Mario Manrriquez and Donald Priesmeyer keep Wharton County Electric Cooperative’s powerful instruments humming.

“My main thing right now is helping with the AMI system,” says Manrriquez from the side of a South Texas road where he and Priesmeyer are installing a communications relay for WCEC’s AMI system.

Over 23 years at WCEC, Manrriquez’s work has changed a lot, but the dangers of the job haven’t. “I almost stepped on a snake once,” he says. “They say good snake, bad snake. I say all bad snakes.”

But Scott Thomas, who was the last full-time meter reader at PenTex Energy in North Texas, will tell you that it’s still the folks at the end of the line who make his job so gratifying.

“The best part is going out into the community and visiting with the customers because every one of them liked to talk and visit,” he says, in between greeting folks by name at the co-op’s annual meeting in April. “You had a schedule, and you tried to stay on schedule, but you had to visit.”