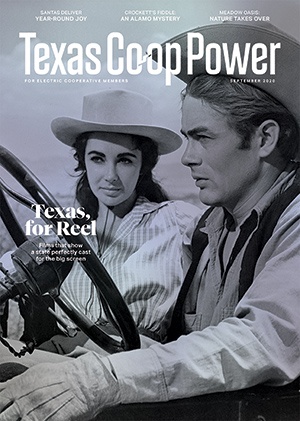

Giant

Giant’s outsize reputation precedes it. The 1956 movie’s 201-minute running time, wide-open West Texas landscape and generations-spanning timeline all connote epic. The film, based on Edna Ferber’s book of the same name, also garnered its director an Oscar. Despite that accolade, and the film’s nominations for a passel of others, some present-day viewers are wary.

“I show this to my graduate students, who expect to hate it, and they wind up—I don’t want to say they love it—but they wind up being amazed by this movie,” says Tom Schatz, author and film professor at the University of Texas at Austin. He acknowledges the movie’s challenging running time and its parallel cultural heft. “In its own way, it’s an extremely progressive movie,” he says, that influenced the perception of Texas as “more nuanced, more sophisticated, and more oriented toward Mexico and the Southwest.”

The Texas Film Commission includes Giant on its Texas Classics Trail, one of the self-guided tours it offers from which cinephiles can build itineraries of film production sites statewide. Since 1971, the film commission has supported the state as a production hub by connecting filmmakers with locations, staff, grants and other resources. Through the choose-your-own-adventure setup of its film trails, the TFC encourages movie fans to explore Texas’ silver screen history while supporting local communities and economies.

The making of Giant accomplished that latter aim, according to Vicki Barge, general manager of Marfa’s Hotel Paisano, a stop on the trail and where the movie’s cast stayed for the first two weeks of production. “At the time it was filmed, it was this huge shot in the arm for Marfa,” she says. “There were four hotels in town, and cast and crew filled every room.”

Even after its famous guests had decamped to private residences nearby, the Paisano remained a hangout. “They took a lot of meals together here, even after they were not living here,” says Barge. The U-shaped bar at the hotel’s restaurant was at that time a lunch counter. Lined with windows at perpendicular angles, it’s easy to imagine the film’s stars—Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson and James Dean among them—lingering there in a desert light-filled inverse of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks.

Elizabeth Taylor, foreground, on the set of Giant. The film’s Reata Ranch and mansion facade are in the background.

Allan Grant | Getty Images

Giant cast photos today line the hotel’s hallways, a primer for the uninitiated, who can watch the movie in full in a quiet corner of the gift shop. It’s an opportunity at least some guests avail themselves of. “They don’t often sit through the entire show but will watch for a while,” Barge says. “It’s a long movie!”

Still, “it’s got its moments,” according to Schatz, “where it’s getting at the human element in a pretty touching way.” The silent, somber homecoming of a Mexican American veteran of World War II; an underdog’s insouciant wave as he exits a meeting; a woman’s acidly articulated response to being shut out of a conversation about politics; and the film’s parting look at two infants, whose contrasting skin tones don’t preclude the sharing of a playpen and a lineage in 1950s Texas, despite the scene’s discordant use of an epithet. “What it’s doing with race and class and gender is pretty remarkable,” Schatz says.

Except for the first few words of Como la Flor in the Monterrey concert scene, Jennifer Lopez lip-synced her singing parts.

Ricco Torres | AFP | Getty Images

Selena

A trailblazer herself, Selena Quintanilla Pérez inspired the eponymous 1997 biopic on the Texas Classics Trail. And though it cites Corpus Christi’s Swantner Park, the waterfront backdrop for a scene in Selena, trailgoers can veer from the official path to the coastal city’s Selena Museum and bayside Mirador de la Flor to learn about the singer, who was murdered at 23 in 1995.

At the bilevel mirador, whose name translates to “viewpoint of the flower,” a bronze likeness of Selena stands, accompanied by narration about the barrier-breaking Tejano artist, interspersed with snippets of Como la Flor. The song was one of Selena y los Dinos’ first U.S. hits and has inspired a swath of genre-bridging covers from artists including country performer Kacey Musgraves and indie duo Dracula. The cumbia’s effervescence almost obscures its narrator’s lament, which likens the end of a love affair to a dying flower.

A performance of Como la Flor in Selena marks the sole instance in Jennifer Lopez’s portrayal of the artist in which Lopez sings, the song’s first few words only, in a scene where her character must calm the crowd at an overcapacity outdoor venue, with the integrity of the band’s stage threatened.

A different moment in the film can be experienced vicariously at the Selena Museum. A studio in which Lopez’s Selena records in the movie—and where Selena herself recorded the song Dreaming of You—is housed at the museum. The studio’s acoustic panels are the same ones that appear in the film, in a scene punctuated with a simple request: “Hey, Dad, pizza!”

Selena’s Porsche, which has a cameo in the movie, is on display at the museum, along with her Grammy—the first awarded to a female Tejano artist for best Mexican American album. Outfits rendered iconic as markers of specific performances are displayed, along with clothing designs sketched by Selena.

Selena in concert in 1995.

Arlene Richie | Media Sources | Getty Images

A less-trafficked corner of the museum bears a collage of Selena snapshots. In many, she’s dressed casually and wears little or no makeup. Her smile radiates joy. In conjunction with Selena, the images hint at the person behind the performer. They also gesture to a lyric in Como la Flor: “Cómo me duele.”

How it hurts.

Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway played the title characters in 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde.

FOTOS INTERNATIONAL | GETTY IMAGES

Bonnie and Clyde

Art imitates life again on the Texas Classics Trail, albeit several hours north and three decades earlier. Pilot Point’s town square is home to the Farmers and Merchants Bank building, where a robbery scene from Bonnie and Clyde was filmed. To commemorate its spell in the limelight, the town north of Dallas hosts an annual Bonnie and Clyde Days Festival, which includes a reenactment of the scene.

Wayne Purser, a longtime member of CoServ, an electric cooperative in Corinth, coordinates, performs in and corrals volunteers for the scene’s annual reprise. Sometimes the wrangling requires some straight talk. In 2019 a prospective Clyde showed up to audition with long hair and a beard. Given the look’s incongruity with hairstyles popular in the 1930s, when the movie is set, Purser put it plainly: “Dude, that’s not gonna work.” The man returned, less hirsute, and clinched the role, earning praise from Purser for his acting chops.

Purser plays the town sheriff in the reenactment, which is rife with antique vehicles, weapons that fire blanks, and actors and spectators in period dress. Whereas the movie scene occurs in and outside of the bank building, the reenactment satellites the Richardsonian Romanesque structure that today appears essentially identical to how it looks in the 1967 film.

The gang races out of Pilot Point’s Farmers and Merchants Bank building in a scene from the movie.

Universal Studios | Getty Images

Though the actual pair of outlaws never robbed Farmers and Merchants Bank, which closed during the Depression, the site doesn’t want for history. The building dates to 1896 and has been home to Farmers and Merchants Gallery, a purveyor of antiques and art, since 1975. The space’s erstwhile identity shines through occasionally. Marly McCullough, the gallery’s manager, has found century-old checks tucked away in drawers used by the bank’s tellers. “The oldest one I’ve come across was from 1906,” she says. “I have a ton of those that I have kept.”

Other handwritten finds have also popped up. A visitor in her 60s came across a book from her childhood. She knew it was hers because she had written her name in it, perhaps around the time a movie about a ragtag group on the lam was leaving its imprint on Pilot Point.

The alchemy of those moments echoes the power of movies to transport. “To me, it’s magical. Like once I step inside there, it’s another world, and the outside world is almost put on hold for a while,” McCullough says. “It’s my favorite place in the world.”

Ellar Coltrane, left, and Jessi Mechler in the final scene of Boyhood, shot in Big Bend Ranch State Park.

Courtesy Matt Lankes

Boyhood

Boyhood is a different kind of movie. It follows its actors over 12 years as they age, change and crisscross the state, then distills that footage into a 165-minute panorama of a fractured Texas family, moored in love, figuring it out as they go. Though its title implies a focus on a single character, the movie offers a naturalistic depiction of the interiority and ecology of a post-divorce family, anchored by Patricia Arquette’s Oscar-winning portrayal of single parenthood. The film is included on the Texas Film Commission’s Richard Linklater Trail, which guides visitors to seven Boyhood sites in Central, Southeast and West Texas.

From its second year of production in 2003 through Boyhood’s 2013 completion, Matt Lankes worked as the film’s still photographer, capturing behind-the-scenes photos of cast and crew. As he was shooting those images, Lankes conducted a parallel photography project on the film’s set: a series of black-and-white portraits of the movie’s four main actors that culminated in his book Boyhood: Twelve Years on Film.

“It was like we became a family over the years,” Lankes says. “It was always a wonderful reunion for the three to five days that we would shoot each year.” The portraits he made suspend time and mark its passage for each of Lankes’ subjects. “We all were watching each other get older,” Lankes says, “and it was amazing.”

The closing scenes of Boyhood were filmed in West Texas in October 2013. Originally intended to be filmed in Big Bend National Park, a 16-day shutdown of the federal government scrambled those plans and diverted the movie’s cast and crew to Big Bend Ranch State Park. Even a cursory look at the film’s final few moments, backlit by a violet and pink sky, show that the finished product didn’t suffer from the ad hoc change in locale.

“Thankfully, you know, that part of our state is so wonderful,” Lankes says. The park’s otherworldly rock formations at its Hoodoos Trail appear in the movie, along with Closed Canyon, whose soaring walls approximate hiking in a natural cathedral.

Boyhood’s protagonist, Mason, college-age at this point in the film, meanders through the canyon with a trio of new friends near the film’s end. “It’s just a beautiful scene—they’re in a real moment, and it’s just kids doing what kids do,” Lankes says. “The landscape is irreplaceable.”

Jessica Ridge is a TEC communications specialist.