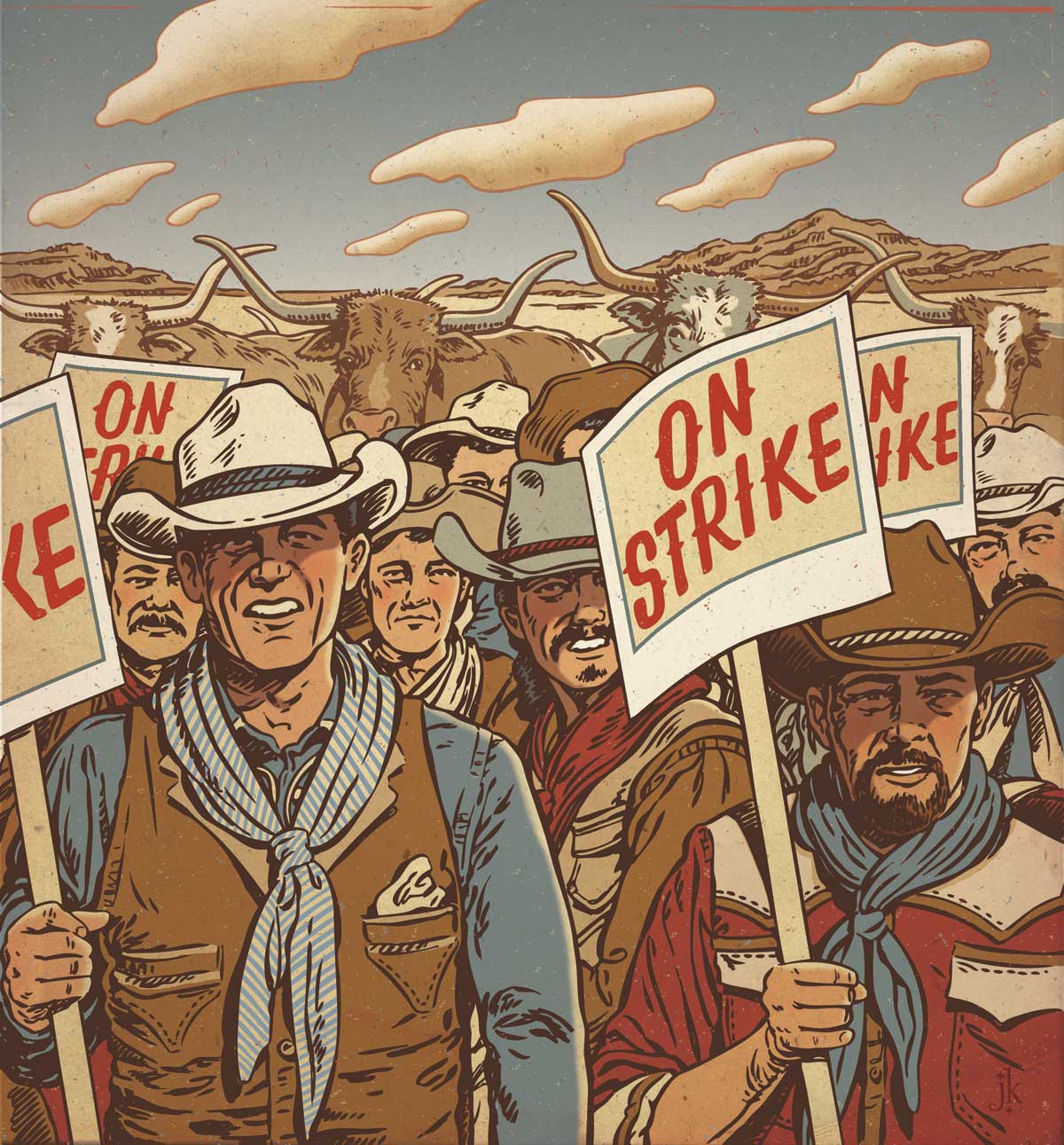

American history is full of images of striking autoworkers, farm laborers, steelworkers, coal miners and others. But cowboys? The notion seems farfetched, even ridiculous. Cowboys are, after all, iconic loners, usually portrayed as independent and self-reliant. It’s hard to imagine a group of ranch hands organizing a strike, but it happened in Texas.

In 1883, in the wild and woolly cow town of Tascosa on the banks of the Canadian River, a group of cowboys got mad as hell and announced to the owners of five big Panhandle ranches that they weren’t going to take it anymore. Between 160 and 200 cowboys walked off the job in what became known as the Great Cowboy Strike of 1883, though it didn’t turn out all that great.

The strike happened at a time when both the cattle business and the plains country of the Panhandle were in transition. The cattle drives were over, and the railroads had arrived. A lot of the old ranch owners were also gone, their places taken by out-of-state and foreign investors.

The cowboy life has always been romantic to those not actively engaged in it—a sentiment especially true for these hired hands. They labored sunup to sundown in every kind of weather doing frequently dangerous work, eating two meals a day and sleeping out in the open, unless they were among the pampered few who had tents. On average, they earned $30 a month.

In the old days before the syndicates and absentee owners, cowboys might be given some calves in addition to their pay, or they could take some mavericks (an unbranded calf or yearling) and work their own herds out on the range. Many a future Panhandle rancher got started that way.

Then ranch owners put an end to all that up-by-the-bootstraps nonsense. They didn’t give away calves, and all mavericks became property of the ranch. This change, more than salary, was at the heart of the cowboys’ discontent.

The cowboys asked for a raise to $50 a month and the same wage for a “good” cook. Bosses would get $75. The strike was intended to disrupt the spring roundup, but it did not. The ranches were not much affected by anything the cowboys did or did not do, though much was made of what they might do.

Newspapers in other states relished the idea of a Texas range war, and a class war to boot! “An ordinary cowboy is as explosive as a nitroglycerin bomb, and a good deal more dangerous. We shall watch with great interest, not caring much which side whips or gets whipped,” the Trinidad, Colorado, Weekly Advertiser commented.

But the strike came and went without a shot being fired, ending only two months after it began. The LE and T-Anchor ranches fired striking cowboys on the spot. The LS and LIT ranches offered a small raise and fired anybody who didn’t accept it. The spring roundups continued with replacement workers, of which there were plenty, and with cowboys who saw the handwriting on the wall and rejoined their old outfits. The strikers simply ran out of money while the work went on without them.

The only lingering effects of the strike were some of Tascosa’s later infamous gunfights, many of which had their origins in festering animosities exposed or created by the strike.

Texas writer Elmer Kelton based his novel “The Day the Cowboys Quit” (Texas Christian University Press) on the strike. Kelton, who died in 2009, understood cowboys and why the strike happened, or perhaps failed to happen. He theorized in the words of the novel’s protagonist, a cowboy named Hugh Hitchcock.

“Hugh Hitchcock always said cowboy independence triggered the cowboy strike,” Kelton wrote. “There came a time that some men decided independence was too costly when the wrong people had it, so they tried to mold others to a pattern of their own cutting. And when you crowd a man too far, he may do something in self defense that is not sensible, either.”

Some scholars have called the strike part of a wider international labor movement, but historian Robert Ziegler, in the Texas State Historical Association’s online “Handbook of Texas,” called it “an interesting but isolated incident that had no lasting repercussions for either the cowboys or the cattle industry.”