Even on a morning thick with clouds, white-flecked Texas bluebonnets pop from a mix of buffalo and other native grasses at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in South Austin. Andrea DeLong-Amaya, director of horticulture for the Wildflower Center, points to sample gardens filled with the dark pink winecup and frosted purple Gregg dalea. She hands me a sprig of white leaf mountain mint, a plant that’s fragrant, peppery and, best of all, a native of the region.

With drought gripping much of the state over the past several years, adding native plants to the garden makes sense for both environmental and economic reasons. Not only do these native, drought-tolerant plants consume less water, but they also use less fertilizer and offer greater disease resistance than nonnative versions. Native plants also can better withstand brief periodic blasts of cold, the frequent hallmarks of a Texas winter.

In addition, many native plant varieties provide habitat and food sources for regional birds, butterflies and other wildlife. Punctuating this fact, bees dive in and out of flowers in the many garden plots DeLong-Amaya and I explore. Pam Middleton, state coordinator of the Native Plant Society of Texas, based in Fredericksburg, emphasizes the biodiversity that native plant species provide—for instance, monarch butterflies and the native varieties of milkweed they consume.

Besides the practical advantages and biodiversity, native plants also keep Texas looking like Texas rather than someplace else. “Planting natives promotes a regional identity,” DeLong-Amaya says, “and they help keep it distinctive by avoiding homogenization.”

Sally and Andy Wasowski, husband-and-wife authors of “Native Texas Gardens,” propose, “Rather than limiting your possibilities, native plants present you with greater flexibility and more options. And more options means getting away from that numbing sameness of traditionally landscaped neighborhoods.”

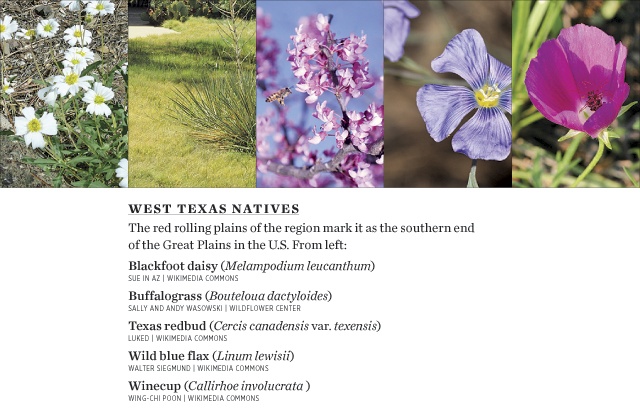

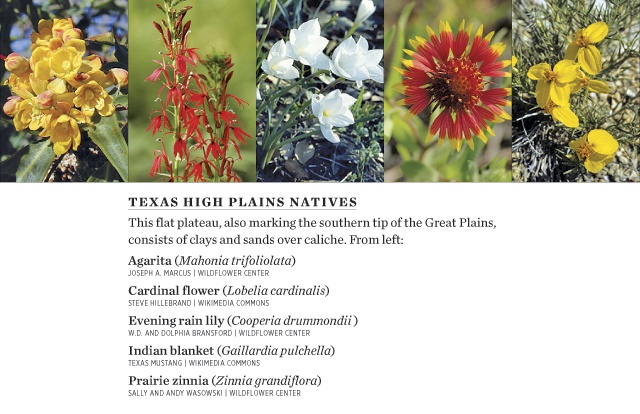

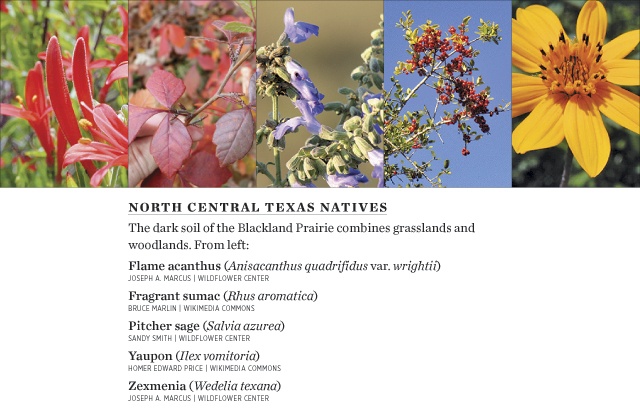

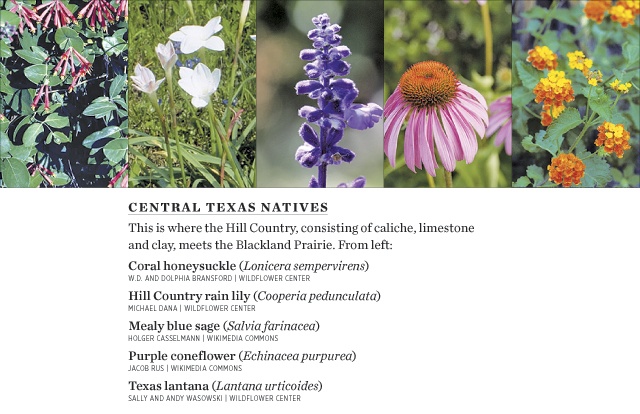

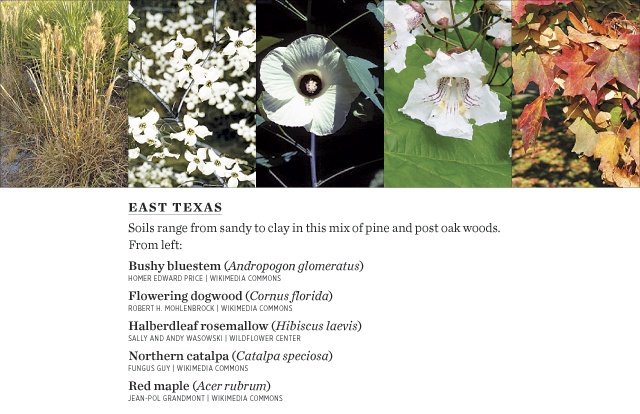

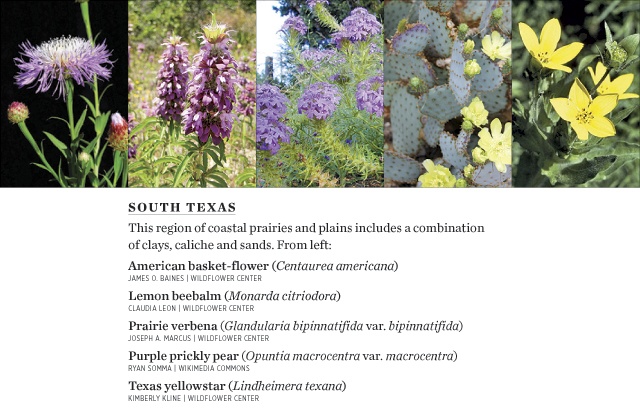

Native plants offer a distinct identity across diverse terrain statewide, from the arid climate of the western regions to the humidity of the coastline. This diversity in climate and topography leads to a rich variety of native plant options for gardeners to explore.

DeLong-Amaya and I admire stands of Indian blanket, also known as firewheel, wavering in showy circles of red and yellow, their edges ridged. This vibrant, heat-tolerant plant grows throughout the state and the Southwest. DeLong-Amaya describes other well-known native plants spanning regional borders, including the Texas bluebonnet, a treasure that thrives in soils statewide and doesn’t grow outside of Texas.

Turk’s cap, another popular and hardy native, grows in a variety of soil conditions and prefers some shade, its miniature red blossoms a distinctive surprise in shadowy alcoves. Spiderwort, which grows in shade or sun, provides a strong accompaniment to Turk’s cap. The soft purple-blue of mealy blue sage, meanwhile, looks good in the garden surrounded by butterflies or as a cut flower in a vase.

While some gardeners include nonnative plants in their yards and gardens, invasive plants—those brought to the region intentionally or by accident—adapt too well and increase in their new location without assistance or abatement. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service describes invasive plants as a species that causes some sort of harm or cost to the ecology, economy and human health.

Invasive plants deplete space for natives, leading to homogenization and loss of habitat. In addition, thirsty invasive plant varieties consume extra water, an added concern in a dry climate and particularly during times of drought. When measuring overall habitat loss, invasive species are second only to habitat destruction in terms of ecological impact, DeLong-Amaya says. In addition, invasive species pose an economic cost to crops, forests and fisheries in the United States estimated at $137 billion annually, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Invasive species also significantly threaten almost half of the federally endangered native species.

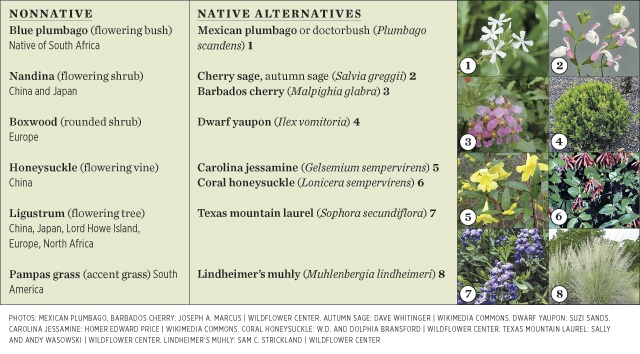

Not all nonnatives are considered to be invasive. Certain garden plants, such as the blue plumbago, have adjusted to the heat of the region without having the long-term impacts of more invasive plants. Many gardeners compromise in their plant selections, growing a mix of native and nonnative drought-tolerant plants. For gardeners who wish to increase their ratio of native plant varieties, solid alternatives are often available. The native Mexican plumbago, for instance, offers white blooms and a heat tolerance similar to the blue plumbago. A few other native plant options for common nonnative plant varieties are listed below. Most of these plants grow statewide.

Many nurseries and plant centers carry native varieties. If native plants aren’t available, DeLong-Amaya recommends that gardeners request them from their nurseries. As part of the Native Plant Society’s Natives Instead of Common Exotics (or NICE) program, the organization’s 34 individual chapters statewide work with nurseries to feature native plants and try to generate publicity about them.

Ordering native plants by seed is an option, while another is obtaining seeds and cuttings from gardener friends who have established plants. In addition, native plant societies occasionally offer plant sales and swaps, and organize salvage field trips, a great way to save native plants from a landscape or site slated for development.

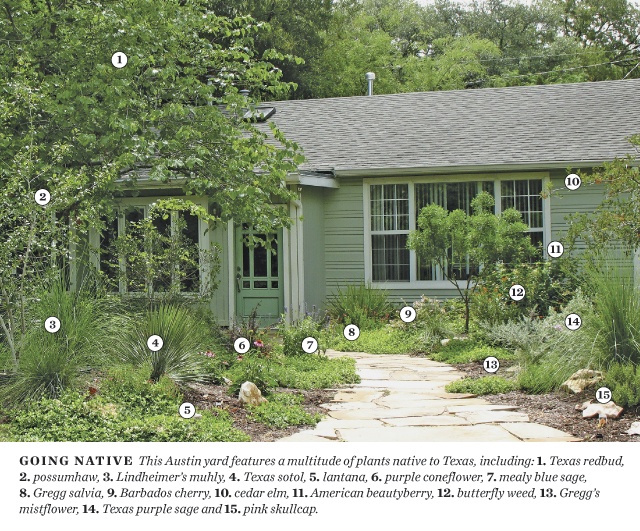

DeLong-Amaya and I tour a series of sample gardens at the Wildflower Center. Although some gardeners favor an unstructured landscape for their native plants, DeLong-Amaya tells me native varieties are also well suited to formal gardens. “A stylized approach with native plants works just as well as the wild, natural look preferred by some gardeners,” she adds, showing me a carefully trimmed plot consisting of native plants, trees and the Wildflower Center’s own drought-tolerant blend of native grasses consisting of buffalo, blue grama and curly mesquite varieties.

Gardeners can blend formal and informal plant elements in a single garden. In addition to the look and feel of the garden, the maintenance time the gardener devotes helps dictate the characteristics and personality of the native garden plot.

Walking away from the native gardens and surrounding grounds of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center isn’t easy, but the many plant options stay with me on my stroll through the last of the sample gardens varying in style from formal to free-form. Visitors stoop over Texas bluebonnets and winecups or look up to admire an arbor covered in lush grapevines, just a few of the many native plant options.

——————–

Gail Folkins is an Austin writer.