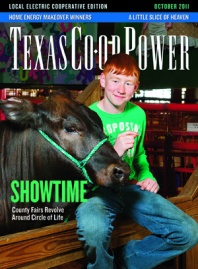

It looks like 9-year-old Lane Henley is leading a ship through the show barn at the Walker County Fair and Rodeo. But there’s no need to clear the decks: The peaceful passage of small boy and a huge steer named Daddy’s Boy creates merely a ripple among bystanders as Lane guides the animal into his stall.

Daddy’s Boy, a jet-black, 1,240-pound Maine-Angus-Chianina crossbreed, outweighs the 50-pound Lane by more than half a ton. And from the hip, the steer stands a good 4 inches taller than the 4-foot-1-inch third-grader who will put him through his paces in the show ring.

But as Lane anchors his steer—“High or low, Daddy?” he asks his foster dad, Alan Bagwell, about where to tie the halter rope on a red, pipe-rail fence—it’s clear from the lad’s smooth motions that he’s in no danger of emotional sinkage. This is just another easy docking of a powerful, gentled animal he’s been working with for the past six months.

With his steer settled in on a clean bed of hay, Lane hops up on a wooden equipment box, sits and extends one foot: “Daddy, will you tie my shoe?”

It’s one of those sweet, innocent moments that slip away, uncaptured by camera or video recorder. Kids grow up fast. Too fast. Yet here at the Walker County Fair just west of Huntsville, and at regional and county fairs across Texas, they sure don’t do it alone.

As evidenced by a steady stream of rural and urban visitors at the 2011 Walker County Fair, country still matters: And country at this East Texas fair, like so many others around the state, means shining an extra-special spotlight on the kinship between youths and animals.

It’s a bond buoyed by family love and support. Drop in on any livestock show barn across Texas, and you’ll see the same scene, year after year: moms, dads, siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles lugging feed and water buckets, cleaning stalls and pushing wheelbarrows. Everybody pitches in.

And you’ll hear the same thread of conversation: “My grandparents showed; my parents showed; I showed, and now my kids are in the ring …”

It’s the circle of life, on and on. It’s the building of relationships, between children and parents, youngsters and animals, youngsters and spectators, youngsters and judges, youngsters and each other. It’s the tried-and-true theme of raising kids, raising livestock, raising the bar on hopes and dreams.

But these young exhibitors know the score: Only one grand champion is named in each livestock division. Only so many belt buckles and trophies are awarded. And they know that their steers, rabbits, goats, lambs, hogs and broilers (chickens) are being judged for meat in what are called—harsh as it sounds—terminal shows. This is the end of the road.

Every year, at shows big and small, tears roll down youngsters’ faces after livestock sales. Some exhibitors snuggle up to their animals in pens and stalls, hugging their necks and whispering soft goodbyes. I remember the cold winter day some 40 years ago at the Garza County livestock show in Post when I watched my steer, one of several I showed as a 4-H member, walk the plank into a livestock truck. Brokenhearted, I held the halter he would never wear again.

Don Ahrens, a 73-year-old director for the Texas Association of Fairs & Events of which the Walker County Fair is a member, showed the grand champion lamb at the 1956 Washington County Fair in Brenham. The experience, Ahrens recalled in a telephone interview, was invaluable: “You put a halter on your lamb; you feed your lamb; you clip your lamb. It taught me to be responsible for something.”

But when a Conoco gas distributor bought Ahrens’ lamb, a ewe, for $90 at the livestock sale, the boy couldn’t bear to see her go. So his dad bought the lamb back and returned her to the family’s sheep herd. She followed Ahrens all over the home place.

For the most part, kids today don’t get that chance: Typically, fair rules statewide dictate that once an animal is sold, it’s gone. But the lucrative upside is that many exhibitors put that sale money toward a college education. And as youths mature into adulthood, there’s something else they can bank on: the priceless county fair experience of learning things like responsibility, humility and confidence that will serve them well the rest of their lives.

I visited the Walker County Fair on a Monday and Tuesday in late March 2011, soaking up conversations with livestock exhibitors, learning East Texas show-barn fashion etiquette (it’s all about the belt buckle, baby), and relaxing on that most iconic of county fair symbols: the Ferris wheel. The circle of life goes on and on.

‘They’re Not in Jail or Trouble’

On a gray, chilly Monday morning, lambs wearing colorful blankets are arriving for weigh-in at the livestock barn. Eddie Smith, a former president of the Walker County Fair Association, is hoofing it up and down the aisles, easy to spot in a red cap and red work jacket as he greets exhibitors and livestock committee members.

Smith recaps the fair’s beginnings in 1978 when a group of parents, educators and community volunteers, including himself, formed the fair association. They started selling association memberships and bought 55 acres on which to start hammering out, literally, the details of the present-day fairgrounds served by Mid-South Synergy.

Smith’s children, Jeff Smith and Jennifer (Smith) Allison, now adults, practically grew up out here. They both showed livestock—lambs, poultry, rabbits, steers and swine—and Jeff also participated in the Scramble Heifer program in which exhibitors may keep their heifers to start their own herds. Jeff did so and had 20 head of cattle by the time he started college.

In addition to their livestock show winnings, the siblings used scholarship money to help pay for college. And Jennifer wore the coveted crown of fair queen in 1990.

Eddie Smith pauses to watch a youngster struggle to hold a water bucket level while opening a hog pen gate. “You better hurry up, you’re gonna lose all your water,” Smith teases the boy.

Whether first or last, Smith muses, these kids are all winners. For sure, they’re learning how to work. “They’re not in jail or trouble,” he says. “They don’t have time.”

‘We’re Growing Kids’

At the hog pens, Kevin and Lisa McKenzie and other parents are settled in Monday morning with canvas chairs and coolers. The McKenzies aren’t going anywhere: Two of their children, 12-year-old Maci and 17-year-old Matthew, are competing in Tuesday night’s swine show, one of the fair’s biggest draws.

The couple’s oldest child, Keith, showed hogs here and now is paying his way through school at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville. Their youngest, 6-year-old Madison, is waiting for her turn in the show ring.

Ask any parent here: Children take the helm in shouldering animal-care responsibilities. But it’s never sink or swim. “We’re growing kids,” says Kevin McKenzie, who grew up showing hogs in the Longview area. “The child is the only one in the ring, but it takes the family together.”

In a nearby pen, 9-year-old McKayla Schultz curls up against her sleeping hog, resting her head on his side and tucking her blue rubber boots beneath her. Her pig’s name is Wilbur, she solemnly informs—yes, just like the one in “Charlotte’s Web”—and her freckles come from her aunt. “This is my sister’s pig,” she says, reaching through the wire fence to pet Pickles in an adjoining pen. This is McKayla’s first livestock show, and she’s adjusting to the experience. “When I don’t feel like I have any friends, I always go to Wilbur,” she says.

‘No Switcheroo’

After lambs are weighed in Monday morning, they’re nose printed for identification: With exhibitors and parents helping hold the animals still, lamb committee member Alan Fry cleans and dries each lamb’s nose, lightly presses an ink pad against both nostrils and stamps the print on a white piece of paper.

Each paper now bears two sets of nose prints: two nostrils from October, when the lambs were first checked in, and two nostrils from today.

One by one, exhibitors sign the papers, attesting this is the same lamb that was ear tagged and nose printed six months earlier. The two sets of nose prints look like a Rorschach test. But they’ll make sense to a small-animal specialist at Sam Houston State University who will verify their accuracy before Monday evening’s lamb show.

“No switcheroo,” Fry says. “We’ve never had one not match.”

Fostering Love

Mike Smith of Huntsville clenches his jaw in anger when asked about the backgrounds of the foster children he’s helping raise, 9-year-old identical twin sisters Kyla and Kyael (last name withheld). All he’s comfortable saying is that they came from a troubled home. But his eyes shine when he thinks about the present. “We’re trying to give them a new life,” he says.

Judging by the girls’ bubbly laughter and ear-to-ear grins, Smith, his wife, Kim, and the whole family are succeeding. Kyla and Kyael live on a farm with Kim’s parents, Roy and Paula Bear, who are serving as the girls’ foster parents. Rural life seems to suit the twins: The fourth-graders are making A’s and B’s as first-time honor-roll students, and they’re showing hogs supplied by Smith. Sitting atop a hog pen with their arms loosely looped around each other, the girls excitedly point out Diego and Ribs, the dark-cross Hampshires they’ll exhibit in Tuesday night’s swine show.

Smith’s 12-year-old son, Dawson, who also has a show hog, hovers nearby in the protective role of big brother while his younger brother, Graham, 7, works out the kinks in the rope he constantly carries. Dawson shakes hands like a man, confident and firm, and introduces Tanner Smith (no relation), his best buddy since pre-K. They’re inseparable.

So are Kyla and Kyael. When asked if they always complete each others’ sentences, the twins respond “Sometimes!” in unison, breaking into wild giggles. As for showing hogs, “It’s a fun experience,” Kyla begins, “but don’t get too attached because you know … they’re gonna leave at one point,” Kyael sums up.

‘Faster, Lane!’

Alan Bagwell and his wife, Charlotte, have built their lives around making sure kids have a home. The Bagwells raised or temporarily cared for more than 50 foster children during the years they worked for the New Mexico Children, Youth and Families Department.

Alan and Charlotte, who moved from New Mexico to the Huntsville area in 2009, took in Lane Henley when he was 10 months old. He was born in Roswell, New Mexico, with fetal alcohol syndrome, a condition that stunted his physical growth. But he’s blossoming overall under the Bagwells’ care.

“Anybody can be a mother and father, but it takes something special to be a mommy and daddy,” says the 65-year-old Alan Bagwell, who is retired.

On Tuesday afternoon, the day before the steer show, father and son are grooming Lane’s steer, Daddy’s Boy, for a photo session. “I’ll hold him, and you brush him,” Bagwell says. “Brush his knees.” Dad turns around, beaming: “They both like to have their picture taken.”

Bagwell tells his son to go exercise Daddy’s Boy in the show arena, which currently is vacant. The steer’s on the heavy side, and the strategy is to sleeken his appearance for the judge. “We want him to walk fast, Lane, so if you have to run to keep up, that’s all right,” Bagwell hollers after the duo. “Faster, Lane!”

Hold on Tight

There’s nothing like losing your grip on your feisty lamb right when the judge is coming your way. So when it happens to 10-year-old Gracie Koonce in front of 300 spectators, she handles the nightmarish situation with the aplomb of a seasoned veteran: She corrals her runaway lamb at one end of the show ring, strong-arms the animal back to the line of exhibitors, corrects her lamb’s stance and pivots to face the judge.

Last year, Gracie’s lamb got away three times during the show, says her dad, Jeremy Koonce of New Waverly. This year, she was better prepared. “I told her, if he got away, just use your cuteness factor and smile and walk it back,” her dad says.

Gracie, wearing a brilliant purple shirt and red fingernail polish, says she was nervous before the show. But she turned near calamity into triumph. “You did real good,” her dad says. “You held onto him.”

‘I’m Just Glad They Don’t Have a Pig’

The baseball manager-like hand signals come fast and furious: Two women, both pursuing animal science degrees at Sam Houston State University, are coaching a high school-age friend during the lamb show. His eyes flit back and forth from the duo to the judge. Finally, the boy gets the universally understood OK sign and thumbs-up. His lamb is standing perfectly for the judge.

For a second there, at least to livestock-show novices, it probably looked like the women wanted their friend to bunt or steal second. But he knew exactly what they wanted. Such is the mysterious language of the show ring: Young exhibitors are out there by themselves, but they’re only a glance away from their home base of family and friends.

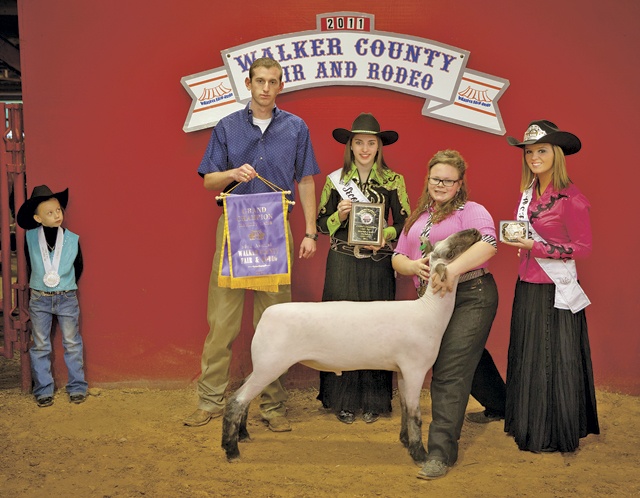

Ultimately, Monday night belongs to Abby Christian, the queen of the show ring, whose grand champion lamb win—along with a grand champion goat crown the day before—gives her a total of six grand championships in five years of showing at the county fair.

As she exits the ring, younger competitors stand in line to touch and congratulate her. “Way to go, Abby,” they say wistfully and reverently, venerating as though in the presence of royalty.

Abby, a sophomore at Huntsville High School, started showing livestock at age 3, in Texas Junior Livestock Association peewee programs. Abby grew up watching her two older sisters show but says it took years to develop what she calls ring presence—a quality born of countless hours of hard work. And despite yet another title won tonight—she’s just been named the lamb-division Grand Senior Showmanship winner—Abby comes across as a quiet and humble teenager who’s a little taken aback by her own success.

“I used to be horrible at showing,” she says. “After my sisters graduated, I stepped up to the plate.”

Did she ever: Abby has won roughly $20,000 in scholarship money, including here and at larger livestock shows around the state. The Christian family name is revered in the Walker County Fair show barn. A fellow competitor walks past the family contingent standing in the aisle. “I’m just glad they don’t have a pig,” he says, laughing good-naturedly.

Emotional Equity

One year ago, she was a calf running wild through the Walker County Fair rodeo arena. Now, Southern Belle is a heifer showing off her power steering as 13-year-old Justin Wilson backs her out of her stall.

Justin is showing Southern Belle through the Scramble Heifer program, which is open to 4-H and Future Farmers of America members ages 12 to 18. Each year, the fair’s rodeo produces 21 Scramble Heifer winners who catch and halter their animals during two calf scrambles. They then show the heifers at the following year’s fair. The exhibitors become the heifers’ official owners at showtime and are allowed to keep the animals to start their own herds.

Justin plans to sell Southern Belle and keep the money for such things as repairing a pickup, but it’s not an easy decision. Each heifer exhibitor, as evidenced by the elaborate record books on display and the hand-painted plywood board signs hanging above the animals’ stalls, has invested a great deal of emotional equity.

Justin’s grandmother helped him cut out Styrofoam decorations for his sign on which Southern Belle is standing upright, wearing a straw hat with a pink corsage, blue eye shadow, red lipstick and a dress with a pink sash.

Southern Belle lies down in her stall, and Justin kneels beside her. They’re a striking pair, with her ebony coat and his short-cropped red hair. “I tell her that she can calm down and that no one’s gonna hurt her,” he says, stroking her side. Justin glances up at the question: Do you love her? “Very much,” he says softly, shyly smiling and returning his gaze to Southern Belle.

Model of Bravery

With cameras at the ready, about 200 anxious mothers, grandmothers, other family members and friends perch on the edge of their seats: We’re moments away from the start of the youth style show as 11 contestants nervously wait behind the stage curtain. The youngsters are in a 4-H sewing club, and each made an outfit to model today. The natural assumption is that all the contestants are girls.

But there’s nothing feminine about the second contestant: 9-year-old Braden Brock, looking cool and collected in sunshades and gray-navy blue-camouflage shorts, struts to the edge of the T-shaped stage, lets the audience get a good look, then turns and self-assuredly exits.

After the show, Braden blames his mom, Shelby Brock, a lecturer and interior design specialist in the Family and Consumer Sciences Department at Sam Houston State University, for making him enter the contest. “It’s kind of freaky,” he says.

But Braden’s big smile tells the truth: He’s proud of his fashionable, cotton-polyester-blend shorts, and an aunt has already asked him to make her a pair. Interest is growing. “I could put you on the list,” he says nonchalantly, hands in his pockets.

Belt Buckles are King

Animals aren’t the only ones being judged: Exhibitors know that they, too, are always on display, whether they’re in the show ring, caring for their animals or having fun with friends on the midway. To be sure, the fair queen and her court reign. But when it comes to fashion, belt buckles are king.

Trophies are nice, exhibitors will tell you, but you can’t wear a trophy around the fairgrounds. Even when 2011 Fair Queen Kaci King and members of her court change from daytime jeans to nighttime formal wear of long skirts over cowboy boots, they generally retain the belt buckle.

Proper belt buckle display is critical: For boys, arguably the coolest look for maximum exposure is to leave your shirt untucked everywhere except behind the buckle. But inside the show ring, you want your shirt tucked in.

For girls, it’s best to always keep the shirt tucked in, but, as with boys, the belt buckle should be big and shiny and carry some significant meaning. For example, it’s very suave to wear a belt buckle you’ve won in competition. It’s also socially acceptable, and encouraged, to wear a belt buckle won by an older sibling.

Beyond the all-important belt buckle, it’s crucial, in terms of stylistic sense, to be ablaze with silver jewelry and shiny rhinestones and sequins, whether on a belt, a headband or the back pockets of jeans. “Flashy is helpful,” says 14-year-old Sydni Duke, who’s showing Marie LeYeau: the heifer queen of Walker County.

Bottom line? You’ve gotta bring some bling into the ring.

‘That’s My Niece’

It’s standing room only for the swine show, with the crowd easily swelling to 500. The bleachers are packed. Some people, to gain a better vantage point, sit or stand on a fence, their boot heels locked on a pipe railing. Below them, hogs and exhibitors enter the show ring from a holding pen.

The scene repeats for each weight class: Exhibitors and hogs come barreling into the holding pen, followed closely by parents holding spray bottles and frantically administering last-minute touch-ups to make the swine shine. “Let me mist him, and then you brush him,” a mother tells her daughter.

A dad chases his daughter into the holding pen, sprays her hog’s rear end, wipes it clean with a towel and smiles at her: “Good luck.”

Inside the ring, depending on how many hogs run wild at once, it can border on bedlam. The more experienced competitors walk slowly, in crouched positions, always keeping an eye on the judge, as they wield show sticks like conductors: tap, tap, swat, swat, from the rump to the shoulder, guiding their hogs, never panicking.

Still, there are traffic jams: “Sarah! Get him off the fence! Show him!” a father yells at his daughter, whose hog is trapped in a corner.

Finally, it’s the moment everyone’s been waiting for: the naming of the grand champion. As 14-year-old Montanah Hatcher comes out of the ring with her winning hog, she’s scooped up off her feet by her Uncle Jeff Snow. He hugs her tight and spins her around. “That’s my niece. That’s my family,” he says, his face beet-red with pride.

Circle of Life

It’s close to 10 p.m. The colorful, spinning lights of the carnival’s midway beckon, but it’s a school night. Come the weekend, its rides will carry laughing, screaming children. As for tonight, the show barn is still abuzz from the swine show. Few people wander out to the midway. There are hogs to tend to and stories to tell.

I’m drawn to the Ferris wheel, perhaps by a need to sit quietly, above the activity of the show barn, to digest the rich experiences of the past two days. It’s a big world down there, inside the show barn and the fair’s exhibit halls. Some people might say it’s a small world, but that would be small-minded.

This is a huge event for youngsters and adults. It’s their fair, their chance to win blue ribbons and belt buckles and trophies. It’s the chance to be seen and accepted, to feel like a champion just for having the confidence to enter a quilt, a photograph, a hand-carved wood project or a jar of bread and butter pickles.

The slow turning of the Ferris wheel, and its softly pulsating blue, green and purple lights entice me to stay on. But the operator’s stopping the ride. It’s time to get off. I look at the bottoms of my shoes: They’re caked with manure. No complaints here. I’m honored to carry home a little bit of the Walker County Fair.

The circle of life goes on and on.

——————–

Camille Wheeler, associate editor