Dress rehearsal was a disaster.

We were 12 men in a community theater production of “12 Angry Men,” a classic courtroom drama. After fewer than four weeks of rehearsals, we were appearing for the first time in front of a live audience—thankfully a small one, just a handful of friends and relatives of cast members for this practice performance.

Things fell apart from the start. Like a series of dominoes, when one actor missed a line, it had a ripple effect, causing another to miss his. That’s because he was waiting for his cue that didn’t come.

Afterward, Jon-Michael Williford, one of the more experienced actors, said we suffered the “quicksand phenomenon.” As things break down, actors lose confidence in others so they tend to jump the gun and deliver their lines early in desperation to stay alive. There were times I felt I was swimming in the ocean, far from shore, on the verge of drowning, desperate to grab onto anything. The old adage is “dying onstage.”

What had I gotten into?

Just weeks earlier, I impulsively showed up for an audition at a tiny theater in Smithville that until recently had housed a barbecue joint. I hadn’t been in a play since high school—some 30 years earlier. I suppose I was intrigued with the compelling story: one juror—Juror No. 8—slowly convinces 11 others that there is a reasonable doubt about whether a 19-year-old man is guilty of stabbing his father to death. I remember long ago seeing the movie, which featured Henry Fonda as Juror No. 8 and Lee J. Cobb as Juror No. 3, the chief antagonist.

My chances of landing a part looked good. I was one of exactly 12 men at the audition. Our director (and theater owner) was john daniels jr., who looked like a refugee from a motorcycle gang: rotund with salt-and-pepper hair pulled back into a ponytail and a limp from a motorcycle accident. (He prefers his name all lowercase. “It’s an artist thing,” said his wife and theater manager April Daniels.)

At the end of the ad hoc “auditions,” daniels cast a number of actors with whom he had previously worked, including veteran Bastrop actor Sam Z. Damon as Juror No. 3. Then, he called me over and offered me the role of Juror No. 8. I was shocked. The Henry Fonda role? Before I thought to decline I heard myself accept. On the drive back home to Austin, any enthusiasm was replaced with anxiety. I soon discovered I had nearly 200 lines. How could I memorize so much in so few weeks?

Every day, I spent hours going over a thick stack of index cards with my lines and cues. Also, I recorded the entire play on a digital voice recorder. Over time, I could—almost by reflex—recite my lines—except when my mind would go inexplicably blank on stage.

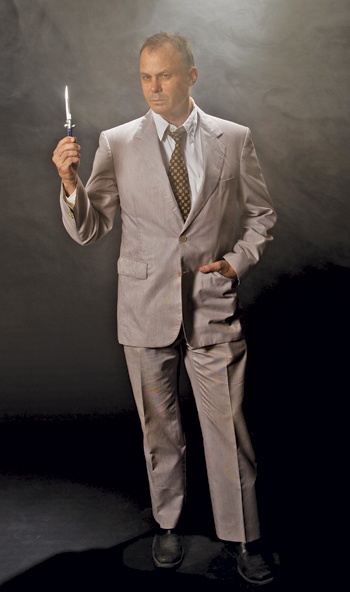

Lines were one thing, but there was more to acting. My character was physical. He re-enacted scenes on the night of the murder and confronted other jurors. In a key early scene, Juror No. 8 surprises the others by pulling a switchblade knife from his pocket, demonstrating that the supposed “one-of-a-kind” knife used to kill the father wasn’t so unusual. For props, daniels bought two identical knives, each of which opened a dull blade with the press of a button. I kept one of the knives in my pocket, since I needed to dramatically pull it out in the first act.

Finally, it was opening night, and I was sure we were destined to flop.

I stayed at a friend’s house in La Grange, only 15 minutes from the theater. That morning, I began going over my lines at 7:30 as I walked country roads. By mid-afternoon, I felt as ready as I would ever be. I loaded my car with my belongings and left the keys in the ignition so as to not misplace them. I dressed in the seersucker suit I was to wear on stage. At 6:40 p.m. I went to the car. Somehow I had left the key in the “on” position. The battery was dead.

The play started at 7:30 p.m. Was I destined to kill the show before it opened? I ran down the dirt road and saw children playing outside a house and a father doing yard work. He was operating an ear-piercing leaf blower. Their entry gate was padlocked. I waved my arms and yelled. I imagined what I looked like: A madman waving his arms and yelling from the road. The man finally noticed and came to the gate, and I explained it was a matter of life and death. He fetched his vehicle, we used my jumper cables to start my car, I thanked him and sped off. I arrived at the theater in a cloud of dust at 7:31 p.m. Within minutes, we made our entrance on stage.

Things started well. The energy was high, and there was a larger-than-expected crowd. I had been in such a rush I forgot to have stage fright. Then I received a jolt: I forgot the switchblade knife!

I had to think quickly. During the upcoming scene, Williford, Juror No. 4, moves to examine the murder weapon. As he made his request for the exhibit I unexpectedly got up and joined him at the door to wait for the bailiff. This was definitely not in the script.

“I need a knife in here,” I whispered to the bailiff off stage, motioning to my jacket pocket. Soon, the bailiff brought back two knives: one tagged “Exhibit No. 1” for Juror No. 4 and the other she surreptitiously slipped into my coat pocket. I felt a surge of relief. We pulled it off without the audience seeing.

The rest of the performance went without a hitch. We made our bows and heard a sweet sound: applause. Over the next few weeks we gave five more performances and received many accolades from theatergoers.

Months later, the experience seems almost a dream. The applause has faded, and I have no immediate plans to return to the stage. I suppose I didn’t catch the theater bug after all. But I’m all right with it. Nobody died.

——————–

Charles Boisseau is an Austin-based writer.