It’s Saturday afternoon at the Fischer Bowling Club, a humble building beneath shady oaks on a two-lane county road in the Hill Country with a red-wood storefront exterior made distinctive by eight white bowling pins arranged in a circle on the wall around a red pin in the middle.

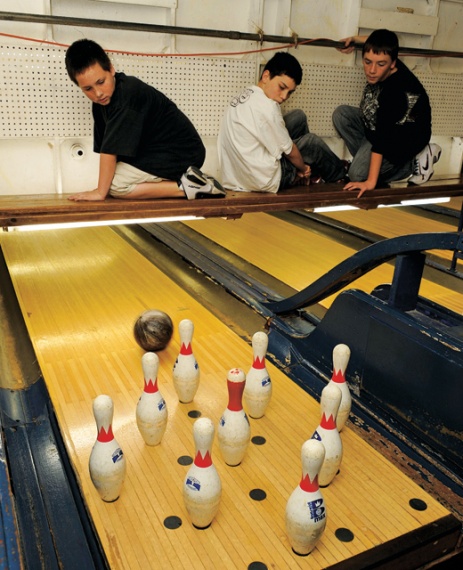

Inside, it feels like a long time ago. Four teams of bowlers are keeping the pin boys at the end of the alley under the Willkommen zum Fischer sign busy, setting up a new diamond-shaped rack of pins whenever all the old rack of pins are all knocked down, or the red pin in the middle, also known as the kingpin, is the only one left standing. The bowlers sit in the rooster benches—as the three rows of bleachers are called—waiting their turn to roll, exchanging pleasantries and small talk, while the team captain records the team scores on the chalkboard by the side of the lanes and calls up the next team bowler.

After rolling balls and knocking down pins for a while, on cue, everyone takes a break, with half of the bowlers going outside to stretch and the other half heading to the bar, popping open $1.50 beers and 50-cent sodas, keeping tabs on the honor system, firing up the jukebox or flipping through the pages of the bowling club scrapbook on the counter while three kids scamper beneath them. After a few minutes’ respite, a petite, gray-haired lady blows a whistle, and everyone goes back to bowling.

Step inside any of the 19 ninepin bowling clubs clustered around Comal, Bexar and Guadalupe counties, and step into Texas as it used to be. Ninepin bowling is one of the last Old World traditions that Germans brought with them when they settled a broad, fertile swath of Central and South-Central Texas in the mid-to-late 18th century. Ninepins were the most popular form of bowling in the early United States, but since the 1930s, when the game was outlawed in several states for its associations with gambling and other shady activities, Texas has been the only place where ninepins remains popular.

Tenpin bowling replaced ninepin, and its popularity was sealed in the 1950s when pinsetters were automated. But ninepin, along with the kids who “set ’em up,” never lost favor in Texas. Today, the tri-county ninepin clubs are the last place in America where bowling is done like this.

Ninepin bowling has a direct connection to a time when social clubs functioned as community centers for German immigrant farmers and others working the fields. It was often the only social option outside the church. Annual memberships under $25, a night of bowling for about $6 and beers under $2 are reminders of how fun used to be a whole lot cheaper and simpler. All one needs to do is commit to bowl one or two nights a week and (for the better bowlers) be willing to travel to “roll-offs” against other clubs.

The functional exteriors of the buildings, ranging from cinder block to limestone to modern metal siding; their low-frills, full-service interiors with tables, chairs, ballrooms, bar and jukebox; and their locations at the edge of cultivated farmland, at crossroads or in oak-canopied oases, are testament to the industriousness and values of the clubs’ founders. The current members, who revel in the old ways despite encroaching cities and suburbs, are testament to the staying power of ninepins.

The specter of the Target sign hovering above the horizon marking yet another power-center mall going up within eyeshot of the Freiheit Bowling Club in New Braunfels does not diminish what the club and the corrugated tin-sided Freiheit Country Store next door symbolize. In the here and now, ninepin bowling clubs not only still function as they were intended to when they were established more than a century ago, they’re cool.

You don’t have to bowl or even go inside to appreciate nuances such as the sign out front of Solms Bowling Club, just south of New Braunfels and just west of Interstate 35, that spells out “Solms Bowling Club 100 Years” in horseshoes. For all the intrusions that so-called progress brings, most bowling clubs have enough land for bar-becue pits, shaded pavilions and horseshoes on the side or around back to get away from it all.

One such example is the eight-lane Mission Valley Bowling Club west of New Braunfels at the crossroads of State Highway 46 and FM 1863. The newbie of ninepin clubs, established in 1943, it remains a surviving slice of countryside in a rapidly developing area. Similarly, it may take some rooting around to find the Bulverde Community Center Bowl- ing Club behind the Bulverde Com- munity Center and next to a school on Ammann Road. Even the Spring Branch Bowling Club on busy U.S. Highway 281 conveys that feeling of refuge. Go around back where the pit and pavilion await under a thicket of oaks, and it still feels like country.

The presence of a ninepin bowling club means a drinking establishment or dance hall is in close proximity, often as not. The Bexar and Germania bowling clubs outside Loop 1604 east of San Antonio are within walking distance of the Double Ringer Lounge (known locally as “Teddy’s”) at the crossroads of Zuehl as well as a public shooting range. The Barbarossa, Bracken and Freiheit bowling clubs are all adjacent to classic beer joints.

The 120-year-old Freiheit Country Store and dance hall has a rep for its griddle-cooked hamburgers, shuffleboard, jukebox and a sign out front that says, “Gun Owners Parking Only, Violators Will Be Shot.” The Fischer Bowling Club, operated by the Agricultural Society of Fischer, which dates back to the 1870s, is adjacent to a 100-year-old dance hall also operated by the society that is available for private functions. The six-lane Blanco Bowling Club is most famous for the Blanco Bowling Club Café in front of the alleys, world-renowned for its truckstop enchiladas and lemon and chocolate meringue pies.

People are perhaps the most crucial ingredient of all that makes ninepin what it is. There’s a lilt in the accents of many bowlers who act like they’ve known each other since they were kids. This may well be the case, since some bowlers go back three or four generations. Listen close, and what you thought was pronounced “bear” for Bexar is referred to as “becks-are” by ninepin bowlers.

Folks at one club seem to know folks at other clubs, as was the case with Kendra, who ran the Freiheit Country Store next to the Freiheit Bowling Club, who said to say hi to Alvin Seiler at the Barbarossa Trough next to the Barbarossa Bowling Club; and with Sharon Coker, the manager at the Laubach Bowling Club, who showed off the bowling pin-themed curtains she redid and gave a brief history of the club founded by the San Geronimo Harmonie as Dean Martin crooned “That’s Amore” on the jukebox. She reckoned that the bowlers in Marion were tougher competitors to go up against in a roll-off than the bowlers over at the Bexar, Germania and Cibolo bowling clubs.

As long as there are good people like Coker, the balls roll, and the pins are reset manually (don’t forget to tip your pinsetter), ninepin remains the only way to bowl in at least one part of Texas that’s like nowhere else in the world.

——————–

Joe Nick Patoski’s latest book is Willie Nelson: An Epic Life.