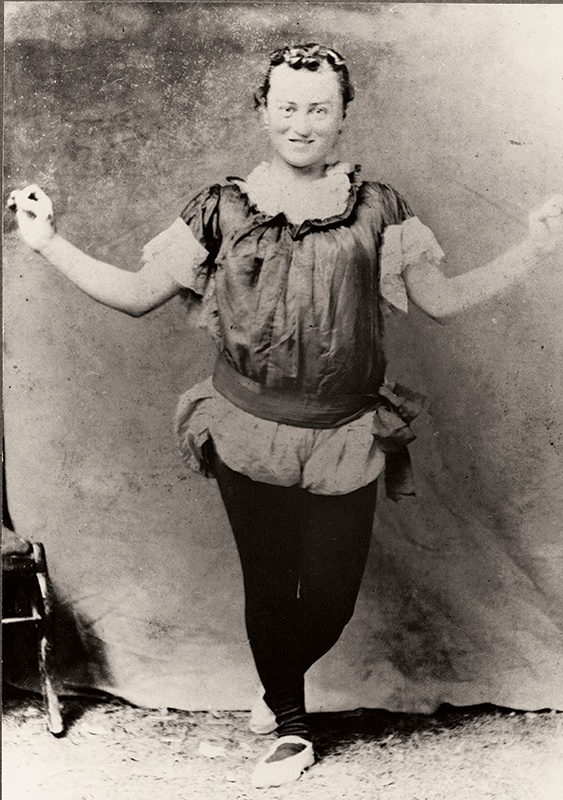

The spring of 1898 witnessed a truly strange sight along the Neches River. Twenty-five brightly colored wagons of the Glasscock Circus lined up at the ferry crossing below the old Tyler County settlement of Town Bluff. Fifty trained poodles and terriers barked in a horse-drawn wagon. Lions paced nervously in another. To entice a surprised crowd into attending the upcoming circus, Alex Glasscock, son of founder John Benjamin Glasscock, led elephants to the river to spray water into the air. His sister, Gracie—a contortionist, trapeze artist and wire walker billed as “LaGracier”—held a parasol as she paraded across the Neches, balancing on the cable wire holding the ferry in place.

Watching the extravaganza from his family’s riverside farm was Jesse Walker. When Walker and Gracie Glasscock locked eyes, it was love at first sight. In fact, Walker ran away from the life he’d known to join the circus, playing in the band and performing clown skits.

Run away and join the circus! Many dreamed of it. Few pulled it off. There’s no doubt, however, that in the late 1800s and early 1900s, countless rural folks—young and old—let their imaginations run away with them whenever circuses or traveling tent shows came to town.

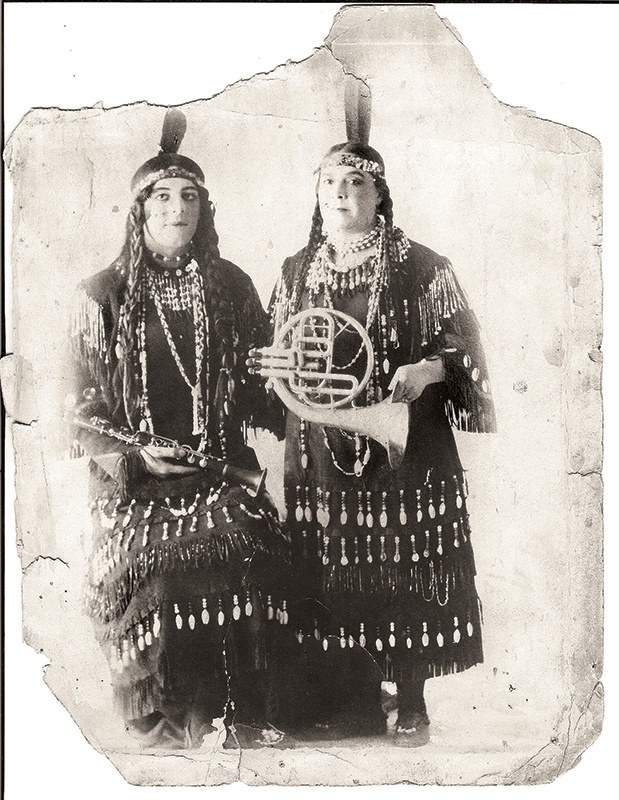

Publicity photo of the Etta Leon Troupe, a vaudeville act. Leon was the wife of Donley Glasscock, one of the Glasscock Circus brothers who toured Texas and neighboring states.

Courtesy of Elizabeth Adkisson

Theater Under Canvas

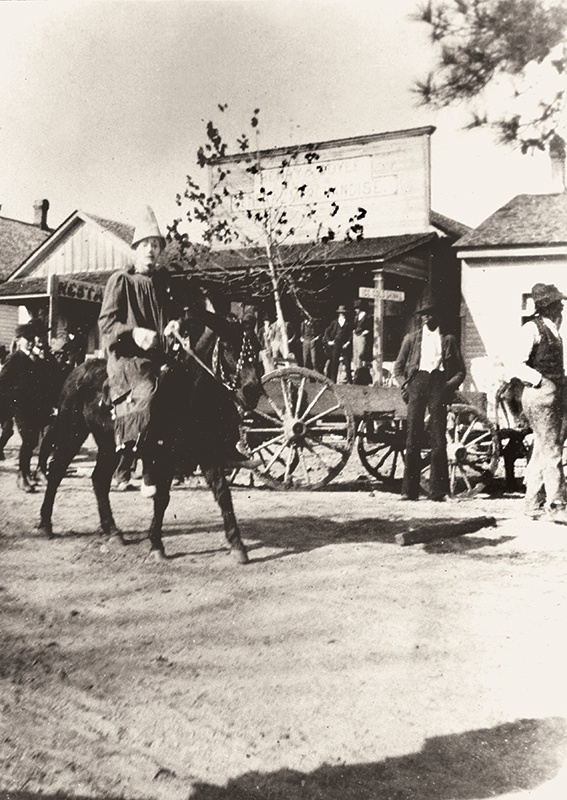

Circuses entertained under the big top beginning in the early 1800s. Though many backwoods communities at first viewed circus shows as immoral, their image improved as circuses added exotic animals and aerial acts. The nation’s railroads expanded after the Civil War, allowing circuses to play every corner of the country. One of the first to capitalize on rail transport was Mollie Bailey, called the “Circus Queen of the Southwest.” Billed as “a Texas show for Texas people,” the one-ring Bailey Circus put its 31 wagonloads of equipment and 200 animals (including elephants and camels) on the rails. At each stop, a parade through town—complete with circus band and marching clowns—drummed up interest for the night’s show.

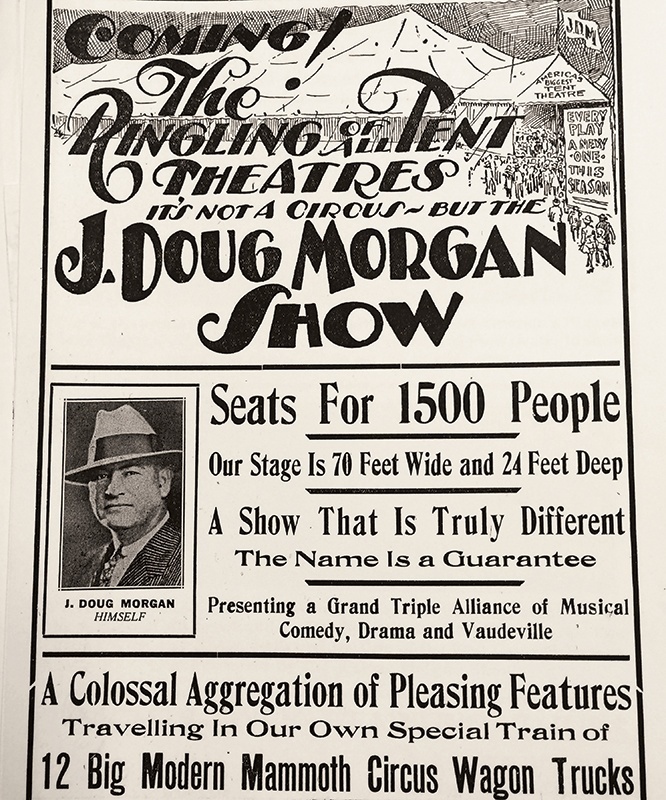

Circuses were not the only big top shows traversing the hinterlands, says Grace Davis, curator at the Theatre Museum of Repertoire Americana in Mount Pleasant, Iowa. A host of small traveling outfits—from magic shows and vaudeville acts to minstrels and medicine shows—entertained country folks in the decades around 1900. Troupes of actors had long performed in small-town opera houses, but that season was limited, so they began staging dramas and comedies under all-weather canvas tents. These tent shows brought the first live entertainment to many isolated communities, says Davis, whose family operated shows for decades. “It was a way actors could make a living,” she says, “because tent shows could move town to town and draw bigger crowds than opera houses, maybe 1,500 people per show.”

Tent repertory companies often consisted of a family of self-trained performers who sometimes wrote their plays or adapted popular standards. Each show followed a regular circuit, returning each year to develop a following. Some shows heated their tents to extend the season, but most took a break, wintering in warm-weather places like Texas. Circuses had “ring” acts, so their tents were round. Repertory theaters, on the other hand, required square ends to accommodate an opera house stage with backdrops. Actors staged a different play each night, averaging three to six shows a week per stop. Such theatrical variety encouraged farm families to pay the 10- or 20-cent admission each night of the annual run. Audiences enjoyed nonstop entertainment. When the curtain closed between acts for set changes, out came a circus-style band, or perhaps a vaudeville act or mysterious magician.

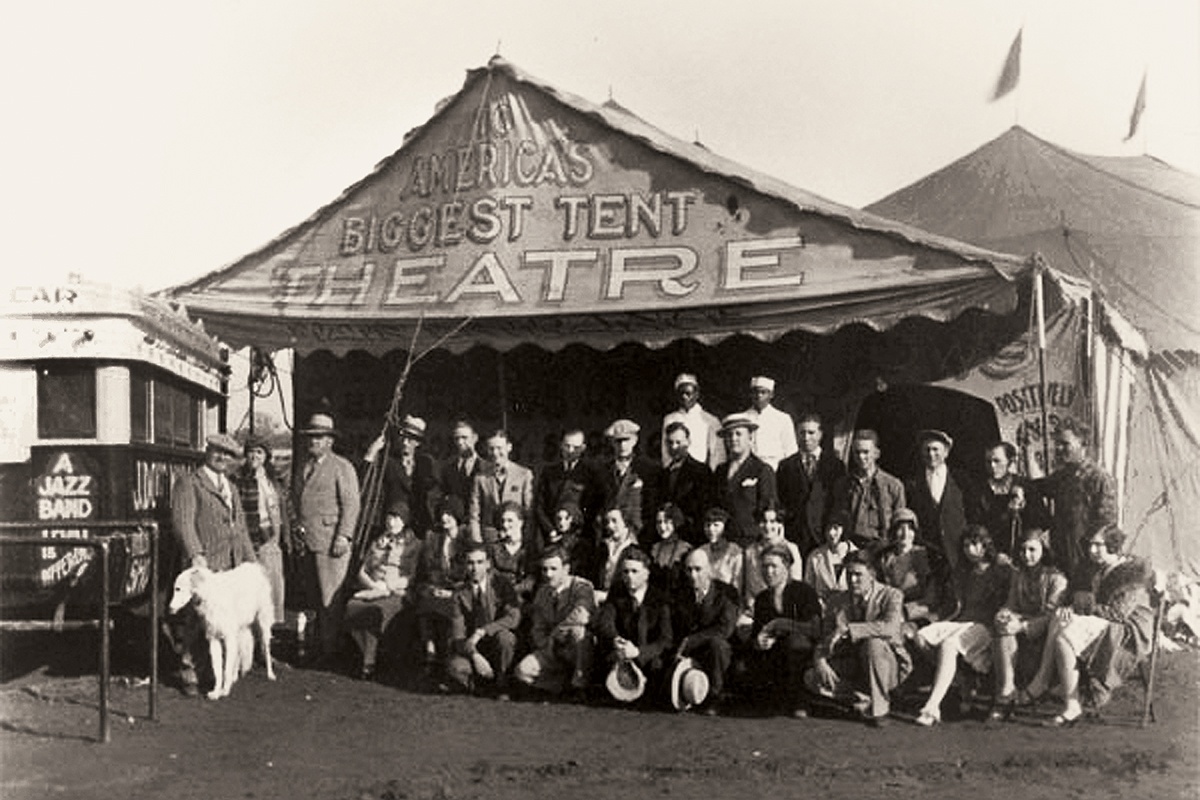

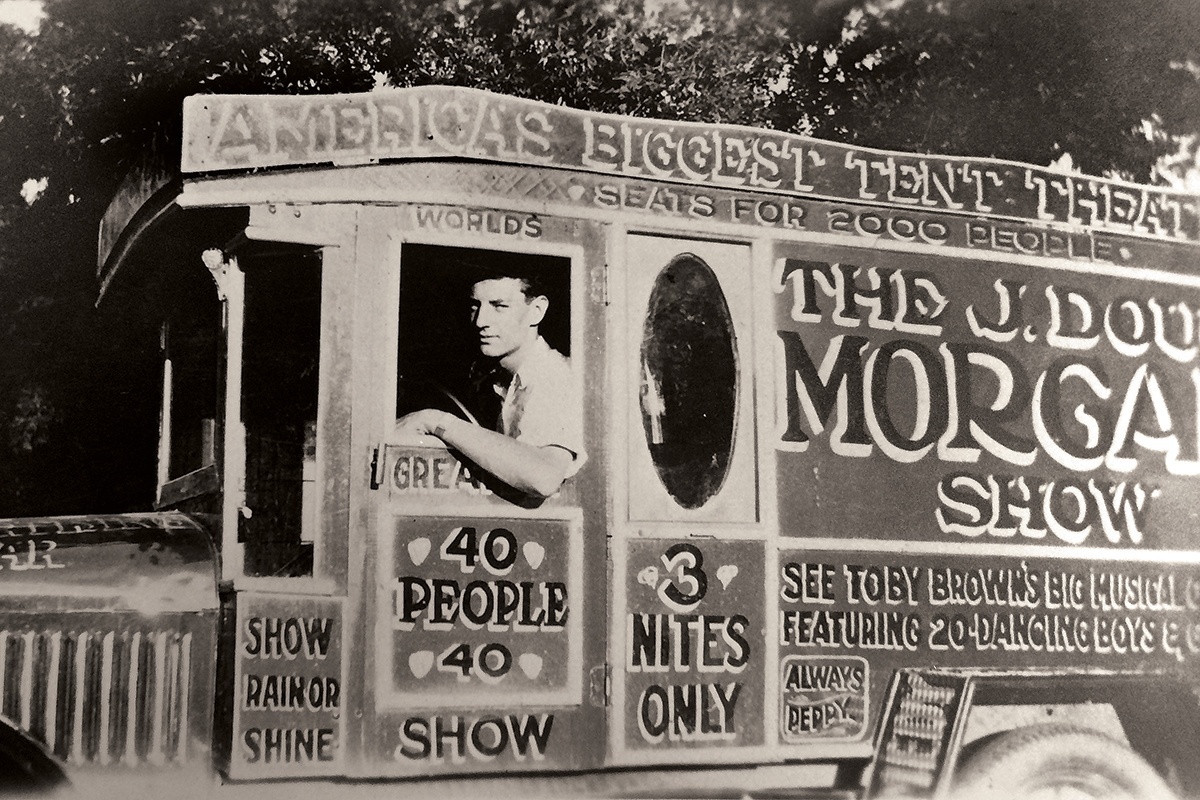

J. Doug Morgan, far left, poses with his performers outside one of several tents that housed his popular show.

Courtesy of Theatre Museum of Repertoire Americana

Plays showcased tear-jerker melodramas, rustic romances and slapstick comedies. A 1916 play called Broadway After Dark was dubbed “a big human play of love and comedy.” A popular temperance novel, Ten Nights in a Bar-Room, proved popular during Prohibition. One enduring standard starred Toby, a redheaded, freckle-faced country bumpkin whose comedic antics solved all sorts of predicaments.

During the heyday of the 1920s, more than 400 units crisscrossed America, with an estimated 100 companies in Texas alone. The editor of Billboard, the entertainment trade publication, proclaimed that “the canvas playhouses of the country now constitute a more extensive business than Broadway and all the rest of the legitimate theatre industry put together.”

Texas Showmanship

One of the most successful Texas tent showmen was Harley Herman Sadler, who left the farm as a teenager to travel with a carnival. He cut his tent-show teeth performing as a comedian in various shows. Then in 1922, he opened his own show, aptly called Harley Sadler’s Own Show. Its 60-stop circuit covered West Texas and eastern New Mexico. Sadler’s lively shows offered country folks a break from hardship and isolation, says Suzanne Depauw May, who co-authored with the late Clifford Ashby the book Trouping Through Texas: Harley Sadler and His Tent Show.

“It was always a very clean, family-oriented show with no off-color jokes. It played mainly small religious communities, where he would donate some of the proceeds to local causes,” May says. “As a small child in Lubbock, I went with my family to see Sadler play Toby the Clown. They were very corny, but we all laughed a lot. It was the first time I’d ever seen live theater.”

Gracie Glasscock, billed as “LaGracier,” grew up in the family circus and performed as a contortionist, bareback rider, trapeze artist and slack wire walker.

Courtesy of Elizabeth Adkisson

Sadler’s hyperbolic promotions billed his show as “the world’s largest traveling dramatic company” and “the most successful repertoire show in America.” Indeed, Sadler became known as “the first man to make a million dollars from a tent show” and went on to find additional success in the oil business and West Texas politics.

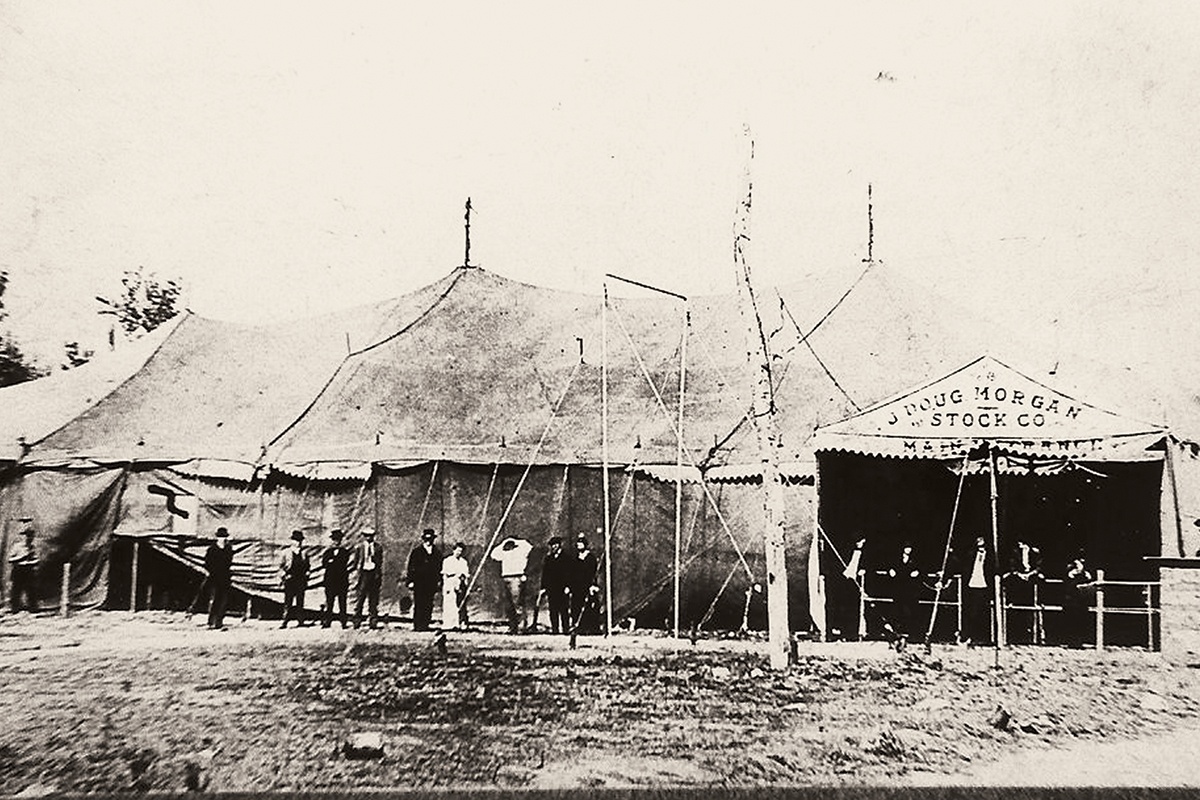

Perhaps the most successful East Texas-based tent show was the J. Doug Morgan Big Tent Show, headquartered at Fry’s Gap, a railroad stop west of Jacksonville. Morgan called his several traveling units “America’s biggest tent theatre.” By the 1920s, he had traveled from Texas through the Midwest with a stage measuring 14 by 34 feet sitting at the end of a 70-foot-wide tent. Portly and conservative offstage, Morgan blossomed on stage as a natural actor. He often starred in his own shows, such as The Lone Star Ranch of Texas, which played the circuit in 1923. That same year, a Morgan ad in a Paris, Texas, newspaper touted “all new plays and vaudeville,” with 30 people performing a week. The Big Hawaiian Orchestra provided music. Jim Bailey of Texas led the vaudeville shows, including performances by Helvey and Montrose, “The Boys Who Sing Their Own songs”; Grande and Deewister, “the Clean Entertainers”; and the Famous Dancing Goodwins, “the fastest dancing team on the American stage.”

Morgan always insisted, “The play’s the thing.” But to keep customers coming, he encouraged a circus atmosphere with bright pennants, barkers and calliope music to “play ’em into the tent.” He often added side attractions, like a carnival with rides, midway and minstrel show. One side attraction was a band hired from a circus that closed. The band, composed of black musicians, raised eyebrows during segregated times, but the band was popular, and Morgan stuck with them. In Iowa, he added a banjo virtuoso he noticed at a local music contest. After a short stint with Morgan, the player, named Smokey Montgomery, joined the Lightcrust Doughboys and eventually became the leader of the most enduring western swing band of all time. During the Great Depression, Morgan even briefly featured a musical hero, Jimmie Rodgers, the “Father of Country Music.” Rodgers’ career (and health) was failing, yet his popular yodeling songs boosted ticket sales for a while. At each stop, Morgan set up a separate tent where Rodgers could rest and regale company members and townspeople with stories of past glories.

A band plays from the Mollie Bailey Circus wagon as the show’s parade passes Henry & Doyle Merchandise store in Livingston circa 1898.

Courtesy of Polk County Museum

The Final Curtain

In 1934, an Eldorado, Texas, newspaper lamented that the town was “ordinarily a good show-town [for Morgan’s tent show], but a three-year depression will tell on any people.” By the time the economy revived, movies, radio and television were replacing live performance as the entertainment of choice. Most repertory shows folded their tents and slipped away. A few survived into the 1950s and even later. Many circuses adapted, consolidated and stayed on the road—and a few remain.

Fewer than 20 years after its fateful crossing of the Neches River, the Glasscock Circus folded and was consolidated into Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, “the greatest show on Earth,” which itself folded in 2017.

The Glasscock Circus’ legacy survives, in part, with Tyler County resident Elizabeth Adkisson. When her grandparents, Jesse and Gracie Glasscock Walker, quit the circus and returned to the Town Bluff farm, they kept their circus past a secret.

“They were afraid what folks might think of them being circus people,” says Adkisson, who retired to East Texas after a career teaching theater. She’s also a certified storyteller who has staged a one-woman show about Gracie, whom she resembles. In her show, she recounts the time Jesse strung up Gracie’s slack wire so she could do a backflip on the wire for the younger generation to see. “So much entertainment history was lost with the passing of that generation,” Adkisson says. But, she adds, she still has LaGracier’s trunk, filled with old circus photos and her heirloom slack wire.

Writer Randy Mallory frequents his family weekend cabin, served by Cherokee County Electric Cooperative, at the community of Fry’s Gap near Jacksonville, the onetime winter home of the J. Doug Morgan Big Tent Show.