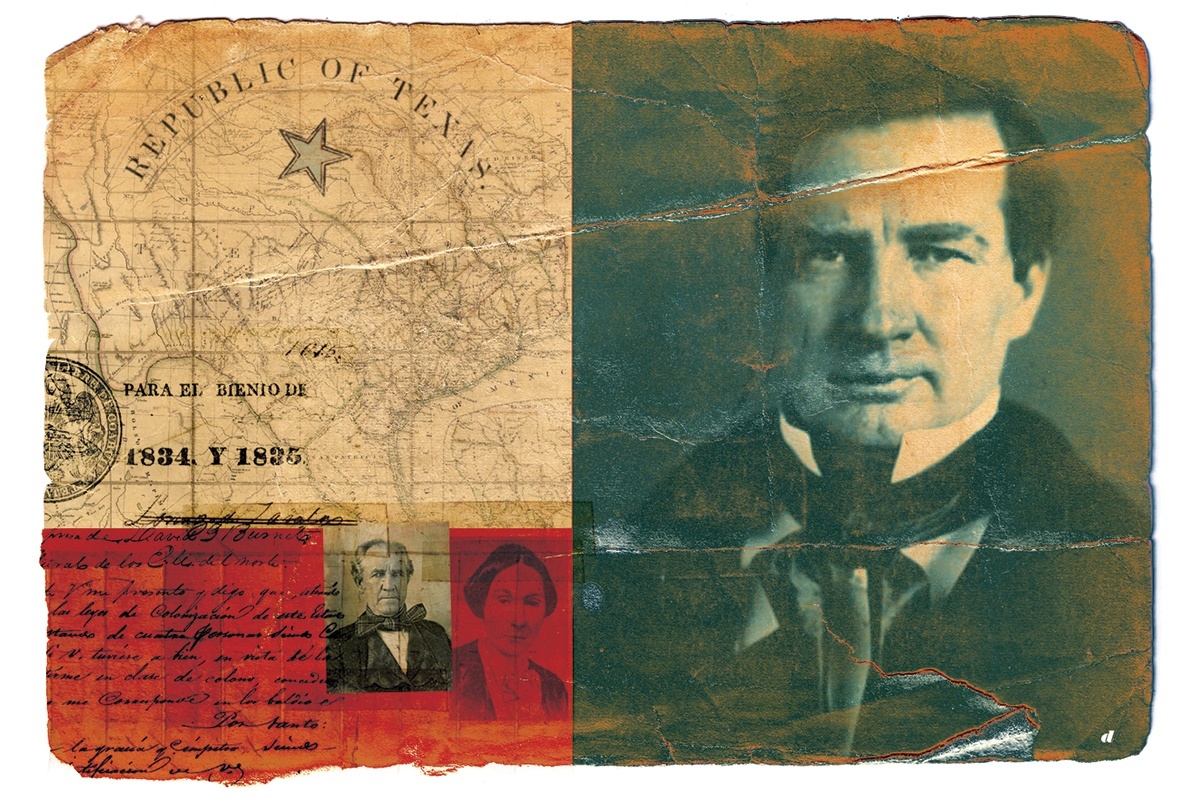

The early Texas Republic was rife with partisanship, and to make it function effectively, the mercurial Sam Houston needed a get-the-job-done counterweight. Fortunately, Thomas Jefferson Rusk came forward.

“Houston was flamboyant. He was larger than life, ” says Scott Sosebee, associate professor of history at Stephen F. Austin State University. “Rusk was your typical genteel Southerner.”

Rusk adapted his skills to a range of challenges. He served as secretary of war for the Texas Republic, inspector general for the army for the Nacogdoches District, chief justice of the Supreme Court for the Texas Republic and U.S. senator from the state of Texas. Rusk was mentioned as a presidential candidate in 1856, putting him on the national stage.

Though a gifted politician, he was also a “moody man and prone to bouts of despair,” says Sosebee.

In 1834, Rusk came from Georgia to the Mexican territory of Texas to recover money embezzled by his business partners. He caught one of the men, who informed Rusk that all of the money had been lost in a card game, according to Charles Swanlund, professor of history at Blinn College in Bryan. Ruined back home, Rusk learned he could get a couple thousand acres for staying in Texas, so he remained in Nacogdoches.

Rusk sensed opportunity in Texas. “There was a chance for him to advance, particularly if the Texas revolution was successful,” says Swanlund. “There was plenty of work for a man like Rusk to do in Texas at that time.”

After organizing recruits to help Stephen F. Austin, Rusk was quickly promoted to inspector general for the army for the Nacogdoches District then to secretary of war for the Texas Republic.

Rusk then joined Houston to help defeat Santa Ana at the Battle of San Jacinto. Swanlund says Rusk wasn’t as volatile as Houston, and this served him well in dealing with his more famous colleague. “They’re both drinking men, and that certainly gave them common ground,” he says. “Rusk was just kind of a middle-of-the-road, down-to-earth guy, and he tried to not really get involved in the personal politics. He was about the work.”

Given the opportunity to become the first president of the Republic of Texas, Rusk declined. He had arrived in Texas to rebuild his personal fortune and had been too busy fighting the war to achieve his goal, so he opened a law practice to support his family. “He always seems to be more comfortable in the background,” says Swanlund.

Rusk played so many roles in Texas history that it’s difficult to choose a defining one. Sosebee believes that Rusk himself would choose secretary of war, an important role that he enjoyed despite his lack of military training. “He liked that military bearing, and being the secretary of war allowed that,” Sosebee says.

Swanlund and Sosebee agree that Rusk’s legacy-defining contribution was as one of the two first senators from the new state of Texas (Houston was the other). True to his get-the-work-done nature, Rusk was instrumental in the Compromise of 1850, according to Swanlund. As part of the accord, Texas was persuaded to give up territory north of the Missouri Compromise parallel and any claims on New Mexican lands. In return, the federal government would assume Texas’ war debt of $10 million. Rusk was such an effective senator that his term was renewed before it expired, according to Swanlund.

In 1856, while Rusk was in Washington, D.C., he received word his wife had died. Later, still deeply saddened by the loss, Rusk committed suicide at his ranch in Nacogdoches.

Rusk managed to thrive in hyper-partisan times with the volatile and contradictory Houston as a contemporary. Among the Republic of Texas’ unsung founders, Rusk has a notable standing.

Robert Springer is a freelance writer who loves Tex-Mex and armadillos.