Once upon a time, tamales appeared only at big family Christmas gatherings and special occasions in the Rio Grande Valley. Besides being tasty treats, aromatic tamales link multiple generations with memories of happy times together. Tamales were already on the menu in Mexico and Central America 7,000 years ago, prepared for ceremonies and armies on the move. Then and now, making tamales—spiced corn dough holding a filling of meats or vegetables or sweet fruits—is a complicated, labor-intensive process. That often prompts a tamalada—a lively gathering of friends and family toiling in the kitchen preparing dozens and dozens of tamales.

Family snapshots show the tamalada tradition that Celia Champion started in 1949.

John Faulk

Starting in 1949, Celia Champion would gather 20–25 female friends and relatives for a tamalada at her Brownsville home as Christmas approached. The women—tamaleras for a day—would make as many as 240 dozen tamales. Wearing multicolored smock aprons and white chef hats, they spread out to workstations around the house to peel garlic, grind spices, stir the masa (corn dough) and grind up the slow-cooked pork shoulders. Others would spread the masa on softened corn husks, top it with meat or beans and three raisins, representing the three wise men, before snugging the corn husk around it all and freezing the raw tamales.

Family snapshots show the tamalada tradition that Celia Champion started in 1949.

Courtesy Celia Galindo

Seventy years later, her daughter, Chickie Samano, and her freckled, curly-haired granddaughter Celia Galindo continue the unbroken tamalada tradition. Two original tamaleras (one 104 years old) attended the six-hour work party in 2018, when the fourth generation included a 12-year-old and Champion’s great-granddaughter. “Once you are in, it’s till death do we part,” Samano says.

“When my grandmother was alive, we would go to the Matamoros mercado to get the best leaves, meat and spices,” Galindo recalls. “Now my cousin Cookie peels the garlic. My friend comes from Seguin with the meat grinder. I grind the spices in a blender.” Nevertheless, she treasures her inherited 200-year-old stone molcajete, worn shiny from decades of grinding spices.

Family snapshots show the tamalada tradition that Celia Champion started in 1949.

Courtesy Celia Galindo

Champion’s original tamalada required arduous labor to make nearly 3,000 tamales. That prompted another tradition. “After making the first few dozen, we drink planter’s punch, and the mariachis arrive. Then the gritos [celebratory shouts] get louder,” Samano explains. “Mother was a party animal, always cooking. On her deathbed, she made me promise we would keep the tamalada.”

A Celia Champion tamalada.

John Faulk

But traditions adapt to the times, so the tamalada now gathers in Galindo’s catering business kitchen. “The ladies want to do less and party more, so we make about 50–60 dozen tamales,” she says. Still, that’s 720 tamales. The women and their families eat the tamales at a Christmas Eve open house, on the religious feast of Candelaria on February 2 and later that month during Charro Days, a celebration of binational cultures and traditions.

The tamaleras also meet on January 6, Three Kings Day or the Epiphany, to eat the wreath-shaped sweet bread called rosca de reyes. The three who find baby Jesus dolls in their slices take charge of organizing the next tamalada.

Luis Reyes became part of a tamale-making team as a boy, joining cousins, parents, aunts and uncles, all under the direction of his grandmother. “Tamale making is an all-day activity. The whole family works together before Christmas,” says Reyes, communications manager for Magic Valley Electric Cooperative in Mercedes.

“Now the family is so big we make tamales twice a year,” he says. “My grandmother loves the American tradition of a family Thanksgiving. She blended that with the Mexican tradition of family tamale making, so we have tamales with the turkey at Thanksgiving.”

Rio Grande Valley parents once warned their unruly children: “Behave or the only thing you will unwrap at Christmas will be a tamale.” Sure, Christmas still finds Hispanic families at feasts anchored by mountains of beef, pork, chicken and bean tamales. But people readily acknowledge that making tamales at home is a time-consuming, fading art, while the convenience of buying ready-made ones is priceless. Hundreds of dozens of the foil-wrapped packets of tamales sell on a daily basis at various commercial tamale-making kitchens, like the one the de Alba family runs in Pharr.

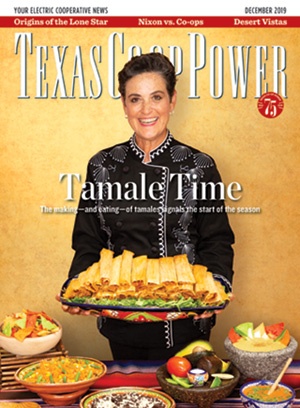

From left: Tanya, Dora and Ana de Alba sample savory, fresh tamales prepared by De Alba Bakery using family recipes.

John Faulk

Inside De Alba Bakery, smiles of a happy crowd get wider as the tamale aroma envelops them. They know from experience the subtly spiced masa of the tamales is as soft as butter and surrounds a savory filling inside the wrapper. De Alba makes 14 different types of tamales, from perennial favorites pork and chicken to Oaxacan vegetarian and bean or combos like cheese paired with jalapeno, beans, pork or chicken.

To satisfy a sweet tooth, De Alba Bakery makes a fudgy Mexican chocolate tamale that comes with Kahlúa sauce as well as a not-too-sweet vanilla-butter tamale common in central Mexico and a scrumptious raisin and cinnamon tamale. As a bakery, it also has shelves brimming with fresh Mexican pastries: empanadas, conchas and hornitos.

Ana de Alba’s grandmother made tortillas and tamales in a small San Benito shop in the 1960s. Her parents expanded that into De Alba Bakery in the 1980s and soon after made tamales available year-round. Today, she is CEO of the bakery, which has two Valley locations, an online store and a staff that has spanned four generations of the de Alba family.

“We’re so blessed to have the border next door to get all the quality, natural ingredients we want—corn leaves, dried chile pods and spices,” de Alba says. The kitchen crew makes the masa from scratch, cooking dried corn for one to two hours before grinding it. Spices and chiles are added to the cooked meats and other fillings, which with the masa are fed into equipment that forms the tamales. Hand wrapping the corn husk around the tamale is the final step.

“Our tamales are stuffed with more meat than the industry average,” de Alba says. “Pleasing our customer comes first, and the bottom line takes care of itself.” In the same vein, De Alba Bakery limits what it ships coast to coast from its website and through Amazon. “Some things won’t ship well without preservatives, and we won’t use them.”

The bakery sells about 50–100 dozen daily, but during the holiday season, it switches to double shifts and brings in additional equipment to meet the demand for thousands of dozens of tamales. Orders for 10–20 dozen are common, although some customers request 100–200 dozen tamales for parties.

A De Alba Bakery tamale with shredded beef and green tomatillo salsa is wrapped in masa and a banana leaf.

John Faulk

“Winter Texans were asking for beef tamales, so we decided to try it,” de Alba says. Dora de Alba, Ana’s mother, who is in charge of tamale quality control and recipe innovation, perfected the beef brisket tamale.

“Mom knew that Mexican women love cooking. She was the first one to provide made-from-scratch masa for sale. That made it simple for women to take prepared masa home and make tamales with their kids without slaving all day,” Ana de Alba says. Making it even easier, De Alba Bakery offers recipes for tamales and other treats in their online blog and stocks cumin, oregano, anise and chiles in the bakery.

A vegetable Oaxacan tamale at De Alba includes zucchini, corn, carrots, peas, onion and a bit of mozzarella cheese.

John Faulk

“Everybody has become accustomed to eating fresh tamales for lunch and dinner all year long,” she adds. “Tamales are faster than hamburgers and taste better, too.”

Eileen Mattei, a Nueces EC member, is a Texas master naturalist in Harlingen.