The trim, 96-year-old woman with neatly coiffed gray hair looks up from her hospital bed at the 6-foot-4-inch blond man bending over her. Patting his white sleeve, she says, ‘It feels strange to have a doctor whose stroller you used to push.’

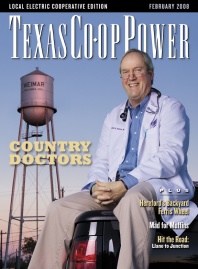

But for a physician in Weimar, population 2,100 or so, the experience isn’t that unusual. Robert Allen Youens was born and raised here. His grandfather Willis set up practice in Columbus in 1907. Robert’s father, Willis Jr., and his Uncle Thomas moved the practice 17 miles west to Weimar in 1947. Residents of Colorado, Fayette and Lavaca counties call him “Dr. Robert” to distinguish him from the now-deceased Dr. Willis and Dr. Thomas. Staff members, some of whom have been with the Youens-Duchicela Clinic for decades, call him “Dr. Bobby.” Except for the three years it took him to earn his bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas, an accelerated three-year program at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and a residency at Brackenridge Hospital in Austin, Youens has spent his life in this Czech-German community midway between Houston and San Antonio, where he gets his electricity from Fayette Electric Co-op.

Youens asks the woman in the hospital bed whether she’s still feeling dizzy. Dizziness and macular degeneration have led to a series of falls, including the latest one, which resulted in a nasty gash on her leg and a concussion. She wants to go home, at least to San Antonio with her daughter, who stands across the bed from Youens. “Would you be comfortable taking care of her wounds?” he asks the daughter, who nods. Then he makes eye contact with the patient, addressing her as “Mrs.” and her surname. Youens’ patients above the age of 20 are “Mister,” “Mrs.” and “Miss,” just as he is “Doctor” to them.

“I’m going to let you go home, but I want to determine two things first,” he explains with a comfortable hint of Central Texas twang as suited to discussing the price of crops at the feed store as to addressing a meeting of the Texas Academy of Family Practitioners, of which he’s incoming president. “First, are you still anemic? Second, can you get up and down?”

Then Youens turns to one of the three residents standing at the foot of the bed. “Dr. Schneiderman, you have a primary interest in geriatrics. What’s the main issue in geriatrics?”

David Schneiderman is stumped, so Youens answers his own question congenially: “Function. We have to determine whether she can be up and around enough to go home.”

Despite hailing from Lima, Peru, with a population of more than 8 million, Schneiderman is firm in his plans to practice in rural Texas. So are his fellow residents, Geraldo Garcia, from Monterrey, Mexico, and Jaime Ruiz-Perez, from Mexico City.

“People like to have the doctor be part of the community,” Garcia says when asked why he wants to be a country doctor. “Dr. Youens goes shopping with them, goes to church with them. That’s what I want to do.”

For 15 years, Youens has been teaching residents and medical students as clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Texas-Medical Branch (UTMB). When newly minted M.D.s and D.O.s enter the three-year program that provides real-world training in birth-to-death care, UTMB family medicine residents can opt for the rural residency track, spending four months in the second year and three in the third away from the Galveston campus in a small-town practice. Texas Tech’s Health Science Center has a similar program, as does the University of North Texas’ medical school. At Texas A&M, the Brazos Family Medicine Residency requires residents to spend four weeks out of each of their three years working with physicians in towns with populations under 9,000. A&M also offers a one-year rural practice fellowship for family practitioners who have completed their residencies and want to experience the realities of country doctoring.

“These programs are important because most of Texas is rural,” explains Dr. Lisa Nash, director of the UTMB program. “A lot of counties have only one doctor. If that doctor gets ill, what does that community do?”

In fact, 21 of Texas’ 254 counties have no doctor at all.

According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, while the number of primary care physicians (family practice, general internal medicine, obstetrician-gynecologists and pediatricians) dropped in 56 rural counties, it rose in 105 between 1995 and 2005. Rural residency programs can take some credit for the improvement, but people living in large, sparsely populated areas of West Texas still face the prospect of driving 100 miles or more to see a doctor. When asked what he’d do if one of his workers broke an arm, a Panhandle rancher replied, “Call the vet.”

As a country doctor in the 21st century, Robert Youens practices differently from his father and uncle, let alone his grandfather. He doesn’t carry a black bag, and he makes house calls only occasionally—for instance, to check on a patient with a broken hip who insists on staying at the farm rather than recuperating at the nursing home next to Youens’ clinic.

Youens holds a master’s degree in medical management, earned online, from the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business. He and his partners totally computerized their practice, switching patient records to a secure electronic database. As of 2002, only 5 percent of family medicine physicians in Texas had done likewise. Electronic medical records check automatically for drug interactions and give the physician access to the patient’s chart even when he or she is out of the office. Although it incorporates 21st century advances, Youens’ approach to rural medicine rests on the time-honored “Four As of Medical Practice”: to be available, affordable, affable and able.

Youens’ day begins at 7 a.m. with rounds at the 38-bed Colorado-Fayette Medical Center, the community hospital his father and uncle founded in 1949. Then, skirting the parking lot, he strolls to the 18,000-square-foot clinic for appointments with patients. Some he’s known all their lives. Others have known him all his. One he introduces as “The Quilter of Weimar.” Another bakes the best kolaches in town. A third was the clinic’s X-ray technician for 37 years. Altogether, Youens and his partners see about 40 people a day. Although half are on Medicare, the doctors also treat a lot of children and young and middle-aged adults for everything from diabetes and heart disease to fractures from farming accidents.

A few rural physicians are surgeons, but most are family practitioners, which necessitates keeping up with developments in diagnosis and treatment of virtually every human disease. That presents a special challenge: how to stay current. Family medicine was the first specialty to require physicians to get recertified periodically. A country doctor with partners can get away to prepare for and take board exams, attend professional conferences and stay abreast of research and new treatments that could help his or her patients. If a family emergency or a wedding or college graduation comes up, leaving town is a simple matter of shifting patients to a partner, who also knows them. A solo doctor either has to close the practice temporarily or call in a locum tenens—a physician who makes his or her living covering for others.

Youens has experienced the challenges of solo practice directly. He joined his father immediately after completing his residency in 1979. After a stroke in 1982 forced Dr. Willis to retire, Dr. Robert retained a national search firm to help recruit a replacement. But as enthusiastic as candidates seemed during the first months, the new physicians didn’t stay long. Asked why, Joan Prihoda, the clinic’s office manager, who grew up in Plum and La Grange, explains, “Honestly? The wives weren’t happy. There’s not much shopping, and you have to go to Katy to see a movie. It’s only 50 minutes away, but it feels far. It takes a certain kind of person to want to live in a small town.”

For a full year in 1989, Robert Youens practiced solo, seeing as many as 70 patients a day but not much of his wife and three children. Then, in 1990, Jorge Duchicela came and stayed. A native of Ecuador who attended the University of Wisconsin on a soccer scholarship and then stayed on for medical school, Dr. Jorge, as he’s known in Weimar, speaks fluent Spanish, as does his sister, Dr. Olga Duchicela, who joined the Youens-Duchicela Clinic in 2000. That fluency is a plus in rural Texas, where many agricultural workers are Hispanic. In fact, patients from Lee County drive past the medical practices in La Grange to see Dr. Jorge and Dr. Olga.

One thing that distinguishes family medicine, wherever it’s practiced, from other specialties is that family physicians treat patients in their psychosocial context. If a woman comes in complaining of stomach pain, a gastroenterologist is inclined to order an endoscopy right off. A family doctor will sit down with the patient, ask, “Was anything unusual going on in your life at the time the pain started?” and listen.

Even if the patient says no, a small-town doctor will often be aware of the daughter’s divorce, the husband’s three arrests for DWI, or other stressors a suburban practitioner might have no way of knowing about.

After 28 years in practice, Youens sees patients at 68 whom he first saw at 40, and patients he first saw at 60 who are now 88. For a rural physician, observing the same patient over decades imparts a powerful personal message.

“You watch these people through the continuum of their lives, and your own mortality becomes very real,” he says.

And today’s country doctors, like generations before them, observe their patients in the full context of the small community where both live. The frail woman in the nursing home isn’t only an 85-year-old lady with Alzheimer’s and chronic lung disease; she’s the retired postmistress.

In an urban or suburban practice, the relationship often goes one way. The patient is the patient, and the doctor is the doctor. But in a rural practice, the relationship is reciprocal. The patient is both the patient and the man who fixes the doctor’s lawnmower or the woman who teaches her children, and the doctor is both the doctor and the regular customer or the member of the PTO.

“On a Saturday morning if I’m not seeing patients, I’ll go down to M-G to buy bedding plants, and then I’ll stop in at the Screen Door, a boutique,” Olga Duchicela says. “The people who work in those stores are our patients. So is the guy who does weightlifting at the fitness center.”

That familiarity cuts both ways. A resident of a small town might not want someone she runs into at the supermarket and high school football games to know the details of her battle with colitis. That’s why some Weimar residents go to doctors in Columbus, and vice-versa.

Occasionally, the rural physician, too, needs some privacy. To relax, Youens and his wife go to Austin—for the restaurants, for the shops, but also for the anonymity.

“I’m a very public person here,” he explains.

Nash says access to a larger urban area, with museums, shopping malls, performing arts and a commercial airport, is one of the main factors that keep today’s rural physicians content with their lives. Facilities at the local hospital are another. (Does it have its own lab for bloodwork? Does it have an MRI machine?) But the most important factor is the lifestyle—not the idealized fantasy of country life, but an appreciation of the pleasures and responsibilities of being fully embedded in a small community.

As one of the most educated and worldly people in town, a rural physician holds a position of exceptional influence. Youens served on the school board. Jorge Duchicela is chairman of SWIFT (Schulenburg and Weimar in Focus Together), a nonprofit dedicated to improving local health and education. Olga Duchicela founded Healthy High, a group promoting health among Weimar and Schulenburg teens.

“You get a lot of respect in a community this size,” Youens observes. “That respect comes from my father and from my grandfather, from generations of doctors who spend their days and nights taking care of people. But you have to earn it for yourself again and again.”

——————–

Sandy Sheehy learned about rural residency programs through her day job as a development officer with the University of Texas Medical Branch-Galveston. Her last story for Texas Co-op Power was “Birth of a Boot” in the August 2007 issue.