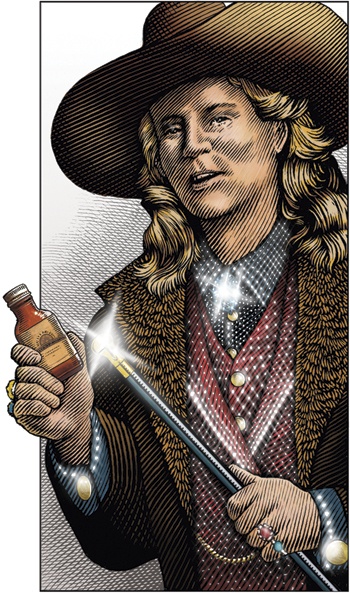

Dr. James I. Lighthall, a medicine show salesman who hawked his elixirs across Texas in the 1880s, was widely known as the Diamond King for his jewel-encrusted costumes. The astounding success of medical quacks like the Diamond King can be attributed, at least in part, to the fact that Texas didn’t have enough licensed physicians to cover its vast area. Practicing medicine was often brutal near the end of the 19th century, when treatments such as bleeding, bone setting and surgery were performed without anesthetic, and many folks weren’t convinced that the licensed doctors’ remedies were any more effective than the cheap patent medicines hawked by snake oil salesmen.

In December 1885, the Diamond King’s Indian Medicine Show wended its way down Commerce Street in San Antonio in a caravan of brightly painted wagons with polished brass fittings. It was not the first Texas tour for Lighthall, but this one would be his last. He stood in the most elaborately decorated wagon wearing a full-length sealskin coat. As his four matched dappled-gray horses trotted along, the Diamond King tossed handfuls of nickels into the street from a nail keg in the back of the wagon. The caravan proceeded to Military Plaza, a large, open-air bazaar, followed by a burgeoning crowd of citizens pocketing the nickels.

Lighthall claimed a connection with Indian healers because of his one-eighth Wyandot heritage. In his book, The Indian Household Medicine Guide, he described his 13 years in Wyoming, Minnesota and Kansas Indian Territories, where he learned about nature’s remedies and “Indian herbal theory” from native tribes. Armed with this knowledge, he began to produce his own medicinal formulas with picturesque names such as Spanish Oil, or King of Pain, Blood Purifier, Liver Regulator, Dentrifice and Indian Hair Tonic. He did not advertise the fact that his potions were made by his mother in Peoria and shipped to him in barrels to be bottled onsite. Most were odoriferous brown liquids containing finely cut herbs, roots and barks supplemented by large amounts of sour mash whiskey and, occasionally, morphine.

When a crowd had gathered, the Diamond King shed his sealskin coat so the customers could appreciate his magnificent attire, described by Vic Daniels in the November 1931 issue of the Frontier Times magazine as, “blazing with what appeared to have been almost a washtub of diamonds, in his hat, on his fingers, in his necktie, his watchchain, decorations upon his coat and vest—everywhere was a brilliance of the precious stones.”

A troupe of up to 10 hired entertainers warmed up the chilly audience with music and dance numbers, after which Lighthall volunteered to pull teeth free of charge. With the spectacular showmanship of a circus performer, he yanked out molars and incisors to the booming beat of an immense bass drum, flinging each tooth high into the air before moving on to the next patient. He claimed to have once pulled 14 teeth in 19 seconds.

Next came the doctor’s mesmerizing health lecture. With silver-tongued brilliance, he convinced the crowd, often numbering well over 1,000, that each was suffering from one of the ailments he described and could hope to recover only with the help of his amazing cures. A small bottle brought 50 cents; large bottles were $1. News reports helped to spread Lighthall’s extravagant claims. “Tomorrow afternoon,” the San Antonio Daily Express reported, “the Diamond King will pitch 40 tents at the corner of Houston and Nacogdoches Streets. The camp will remain several weeks and the public are cordially invited to visit and inspect the greatest Indian medicine company ever organized.”

At least some of these articles were paid advertisements disguised as news stories. Other newspapers weren’t so benevolent. The New York Tribune commented that he had suckered “Texas greenhorns” out of a fortune with his “quack nostrums.”

But even his detractors admitted that Lighthall was not above an occasional good deed. The poor sometimes were handed their bottles of medicine wrapped in $10 or $20 bills. During a tour of Mexico, the Diamond King found himself in the midst of a smallpox outbreak. He was reported to have closed his show and taken his medicines into the villages, treating the afflicted without charge.

But in January 1886, a month after his hugely successful tour of San Antonio began, Lighthall contracted smallpox and died. His own medicines were not potent enough to save himself.

——————–

Martha Deeringer is a frequent contributor to Footnotes in Texas History.