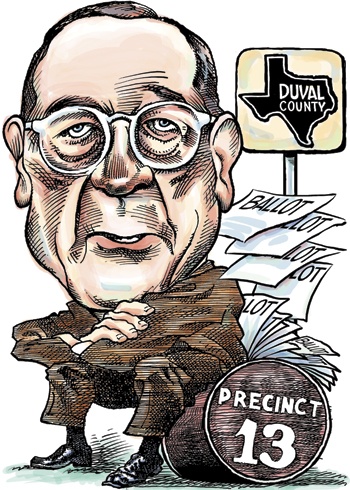

The recent scandal in which the governor of Illinois was accused of trying to sell a U.S. Senate seat just goes to show that Texas is not the only state where politics sometimes goes out of bounds. But for sheer audacity, we’ll put historic Duval County boss rule in South Texas up against anything Chicago or New York ever dreamed up. The reign of the dukes of Duval from 1906 through 1975 was a brush-country saga of graft, shootouts, unsolved murders, arson and the infamous case of the ballot box from Precinct 13.

Archer Parr, the first duke, and George B. Parr, the second duke, were Anglos who gained their power through patronage of the impoverished Mexican-American majority who toiled on area farms and ranches. In contrast to the Anglo landowners who preceded them, they at least took the time to learn Spanish, and they helped people in need—as long as the people stayed within their flock. It was said that Duval County was their milk cow. The Parrs skimmed off the crema (cream) for themselves and left the leche flaca (skim milk) for their followers.

Archer Parr was first elected to the county commissioners court in 1898. In 1912, his side stole the ballots in the county seat, San Diego, triggering a gunfight in which three local officials were killed, according to The Handbook of Texas. At its height, the regime controlled several counties and all county jobs and contracts. The machine oversaw the selective distribution of poll taxes (that had to be paid for the privilege of voting), distributed marked ballots to illiterate voters, posted intimidating armed guards at election sites and, on occasion, tampered with returns.

Opponents’ best recourse was the courts. They pushed for Duval County’s first financial audit in 1914. The preliminary report revealed 14 types of illegal activity. That’s the point at which a mysterious fire destroyed the courthouse and most of the remaining evidence. The investigation turned to cinders, and Archer Parr won election to the Texas Senate.

The Parrs were frequently brought up on charges of unpaid back taxes, mail fraud and perjury. In 1936-37, George Parr served a term in federal prison for income tax evasion.

Fast-forward to 1948 when Lyndon B. Johnson was in a close contest against Coke R. Stevenson to represent Texas in the U.S. Senate. The Handbook of Texas says, “With Stevenson the apparent winner, election officials in Jim Wells County, probably acting on Parr’s orders, reported an additional 202 votes (in Precinct 13) for Johnson a week after the primary runoff and provided the future president with his 87-vote margin of victory for the whole state.” The voting lists from Precinct 13 disappeared, leaving Stevenson’s supporters to allege that many of the late votes were so well organized that they were cast in alphabetical order in the same handwriting using green ink. People even voted from the great beyond.

George Parr controlled elections and freely accessed public funds for personal and public use. He built county roads with his own road company and a racetrack at his ranch. Always willing to do his part, Parr would pitch in and do a stint as county judge or sheriff when the need arose. That he was able to hold public office after serving time for income tax invasion was due to a presidential pardon he received from Harry Truman in 1946.

In the 1950s, George Parr and his ring members were indicted more than 650 times, but Parr survived the indictments. With such a history of crawling intact from the wreckage of various investigations and charges, Parr might have decided, with some justification, that he was invincible. Former federal prosecutor John E. Clark wrote in his 1995 book The Fall of the Duke of Duval that Parr “settled down to an uninterrupted decade of running the county for fun and profit. Not until 1972 would the empire be challenged again.” Clark managed to win a five-year sentence against Parr for income tax evasion.

But George Parr had no intention of going back to prison at the age of 74. His family heritage was as bloody as any spaghetti Western. He drove to a favorite part of his Los Harcones Ranch and put a bullet through his head. On the day of his funeral, 150 cars slowly followed the coffin from the ranch house to the family cemetery where hundreds of still-loyal followers ringed the wrought-iron fence to watch interment and weep.

——————–

Kaye Northcott is editor of Texas Co-op Power, and Clay Coppedge is a frequent contributor.