Along the Brazos River in southeast Bosque County, Albert Redder’s patient digging uncovered the small skull of a juvenile in the earth of a rock shelter. Redder and his friend Frank Watt, avocational archeologists who lived near Waco, had been excavating the site on weekends since 1967. During the summer of 1970, they made the kind of discovery of which archeologists dream.

Once they’d found the skull, Redder and Watt decided to return during a three-day weekend with friend and helper Robert Forrester, who camped near the site. The three knew it was important to finish recovering the remains before looters had a chance to pillage.

“It took us three days to excavate the burial site,” Redder recalled. “We were cleaning up the first skull and realized, hey, there’s another skull; it was two burials!”

The smaller skeleton was curled around the back of an adult male. And there was more. Three turtle shells rested under the man’s head; another under his pelvis; and a fifth shell covered his face. Other findings included claws from Swainson’s hawks and a badger, along with coyote teeth, antler tools, shell beads, and 19 slabs of limestone resting on top.

Redder knew the burial site they’d uncovered was old, but exactly how old? Radiocarbon tests showed that the shelter was about 11,200 years old. This was a significant Paleo-American site and one of only three discovered sites in America found containing burial goods.

“This burial occurred before Greek civilization, pyramids, China. Before any known history, we tack on another 4,000 years, and it boggles the mind,” says Dr. George Larson, director of the Bosque Memorial Museum in Clifton. “History here is much older than you ever imagined.”

The significance of the site is emphasized by the fact that a National Geographic Society TV documentary on the Horn Shelter will be aired in the next few months.

Frank Watt continued to work the site until he was 90, three years before he died in 1979. Redder carried on alone into the 1990s. During their 26 years of excavation, they removed 60 boxes of artifacts.

Redder always wanted to share this historic discovery with Bosque County. Money from Museums for America, a grant program of the Institute of Museums and Library Science, and donations from many friends of the Bosque Memorial Museum in Clifton have culminated in the opening of a new Horn Shelter exhibit in October. The findings and exhibit were named after landowners Adeline and Herman Horn, who gave permission for the artifact hunters to cross their property in order to have access to the river caves.

On the recommendation of Dr. Doug Owsley, renowned physical anthropologist and curator for the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, the Bosque Museum arranged to re-create the face of the adult male skeleton and manufacture replicas of artifacts from the shelter.

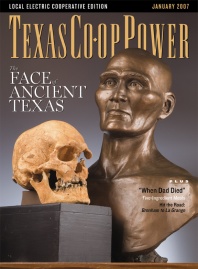

The bust of the county’s oldest-known resident, in fact, the oldest-known Texas resident—a handsome fellow—stands at the entry of the museum.

Amanda Danning, artist and environmental exhibitor for the Horn Shelter exhibit, created the bust in consultation with Owsley. She calls the figure “Sam,” or Son of America, because he can’t be easily classified. “We can’t say he’s American Indian, European, Asian; he’s part of an ongoing study of who lived here,” she says.

Owsley believes that this skeleton, a strong example of a Paleo-American, might be a member of an ancient people called the Anai.

Sam, who scientists estimate was in his 40s when he died, was probably a person of significance given the intricacy of his burial process, from the carefully placed turtle shells around his face and body to the shell beads Redder and Watt found, which had to come from several hundred miles away and probably were considered valuable. Such funeral offerings indicate a care and concern for the dead and could imply that the Paleo-Americans believed in an afterlife.

“Someone took a lot of time putting these two together,” she said, referring to the man and child found curled around him. “From the care taken and number of items buried with him, he was someone of importance.” Danning guesses the ancient man might have been a healer or a storyteller.

The younger figure found was around 9 or 10 years of age at the time of death. Scientists haven’t determined whether the two remains are genetically related.

As a result of unceasing labor by avocational archeologists and strong support by area residents, Bosque Museum visitors can experience the Horn Shelter as it appeared 11,200 years ago, when the Brazos River spread a mile wide and swirled into a confluence that helped create this cave-like shelter.

“We were very pleased to have the community support,” Larson said. “Over half of this support came from local residents; we didn’t have to twist arms, they gave.”

Within the burial site re-creation, the museum has included replicas of elements found at the site, from badger claws to small tools. In a nod to the significance of the burial, Danning added a third figure to the exhibit, a person attending to the two bodies

The Horn Shelter site and the findings within it give both scientists and residents a new glimpse into a period that is on the frontier of anthropology. To Redder, who still occasionally helps at different sites, such detective work also adds to our knowledge of the area. Larson agrees and thinks there are additional places to learn from.

“There are probably more sites in Texas,” Larson said. “It’s just a matter of finding them.”

Gail Folkins wrote “Texas Dance Halls” for the January 2006 Texas Co-op Power.

The Bosque Museum is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays. For more information, visit bosquemuseum.org.

McLennan Electric Cooperative and United Cooperative Services provide electricity for Bosque County.